More Done With Pens Than Swords: Harriet Beecher Stowe and the Book That Rocked America

One night, an enslaved woman named Eliza runs away.

She’s overheard talk that her son is to be sold, and she can’t bear to be parted from him. She runs, a posse of men on her trail. She rents a room next to a river so that her son can rest for the night. She stares out the window at the river…it’s spring, and the water’s still frozen over— with the ferry not running, she doesn’t know how she’s going to get across. But she will do anything to save her son from being sold away from her. Here’s a passage from a book about her story, at the moment when her owner finds her in that rented room:

“In that dizzy moment her feet to her scarce seemed to touch the ground, and a moment brought her to the water's edge. Right on behind they came; and, nerved with strength such as God gives only to the desperate, with one wild cry and flying leap, she vaulted sheer over the turbid current by the shore, on to the raft of ice beyond. It was a desperate leap--impossible to anything but madness and despair; and Haley, Sam, and Andy, instinctively cried out, and lifted up their hands, as she did it. The huge green fragment of ice on which she alighted pitched and creaked as her weight came on it, but she staid there not a moment. With wild cries and desperate energy she leaped to another and still another cake; stumbling--leaping--slipping--springing upwards again! Her shoes are gone--her stockings cut from her feet--while blood marked every step; but she saw nothing, felt nothing, till dimly, as in a dream, she saw the Ohio side, and a man helping her up the bank.”

It reads like a harrowing memoir, doesn’t it? The true-life narrative of someone who was once enslaved? But no: in fact, it’s from a novel. The 19th century’s best-selling and most explosive blockbuster—and the first internationally bestselling novel written by an American woman.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin was the 19th-century’s Fifty Shades of Grey: that book that EVERYBODY read, whether they loved or loathed it, because to NOT read it was to miss out on a crucial piece of cultural context—a social commentary for the times. This book ALSO had taboo topics in it, and involved whips and chains—but not the sexy kind. Uncle Tom’s Cabin was a novel bent on social justice. It was about the horrors of slavery, meant to illustrate the harrowing hurts and indignities enslaved people suffered, and to shake white people out of their complacency about the part they played in that suffering. It was, without doubt, the most talked about piece of writing of the era. It fanned the flames of emancipation, and maybe even the Civil War.

And it wasn’t written by a venerable white guy: a Thoreau or a Hawthorne. No, it was the debut novel of a 39-year-old working mother who desperately wanted to change the world. In this bonus episode, we’ll explore how - and why - this northern woman wrote this incendiary novel, and how it went about changing the way white American women thought about the peculiar institution.

Let’s find out what all that fuss was about, shall we?

my sources

America’s Women: 400 Years of Dolls, Drudges, Helpmates, and Heroines. Gail Collins, HarperCollins 2003.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin: Or Life Among The Lowly. Harriet Beecher Stowe. Freely available via Archive.org.

The Harriet Beecher Stowe Center. A great place to find out all about our girl Harriet!

The Harriet Beecher Stowe House website.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin in the National Era blog.

“Harriet Beecher Stowe.” National Women’s History Museum website.

“Harriet Beecher Stowe.” Biography.com.

“The Story of Josiah Henson, the Real Inspiration for ‘Uncle Tom’s Cabin’.” By Jared Brock, Smithsonian.com, May 16, 2018.

“How Harriet Beecher Stowe was Inspired to Write Uncle Tom’s Cabin” by Nava Atlas. Literary Ladies Guide, Jan. 8 2015.

“Stowe’s Life and Uncle Tom’s Cabin.” Joan D. Hendrick, University of Virginia, 2007.

An illustration of Eliza and her son running over the icy river. Yes, you’re right: they do look awfully white…hmm.

Illustration from Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Archive.org

transcript

Please forgive any typos - I do my best - and know this won’t be exactly the same as the audio version. i ad-lib a bit as i go along.

Harriet Elisabeth Beecher was born on June 14, 1811, in Litchfield, Connecticut. She was one of a whopping 11 children born to the fabulously named duo Roxanna and Lyman Beecher. Roxanna died when Harriet was young, sadly, but poppa Lyman did what most 19th-century men do and takes another wife: a beautiful young woman named, unfortunately for clarity, Harriet. She had several more children, bringing the family child total up by three.

Lyman is a fiery preacher, took up a lot of space. He was a big presence, with intense religious feelings. Those feelings were persuasive, it seems: all seven of her brothers will go on to become ministers, which in the 19th century means becoming organizers, speakers, and sometimes even social justice warriors. The most famous of these, women’s rights proponent and wildly popular public speaker Henry Ward Beecher, was involved in one of the era’s biggest sex scandals. You know, amongst other things.

The Beecher clan was serious about getting things done.

Courtesy of the Harriet Beecher Stowe Center.

But let’s talk about the Beecher ladies. This family is filled with real overachievers, several of them women of the pen. The eldest sister, Catharine Beecher, practically raises her many siblings, helping to set them up for success. But she also goes around founding schools, travels the country raising money for welfare projects, and founding the American Women’s Educational Association. Somewhere in there, she also writes quite a famous book of her own, called A Treatise on Domestic Economy. It’s part celebration of women as domestic goddesses, part helpful how-to manual for homemakers, part treatise on why well-educated women are the very best kind. She believes wholeheartedly in the cult of domesticity, but also that to be good wives and mothers of the future generation, girls need to go to school and learn both philosophy AND how to do laundry: or, as she put it, be “initiated into the arts and mysteries of the wash tub.” Yes, trying to get out wine stains…a mystery indeed. Another, Isabella Beecher, is a leader in the suffrage movement, publishing essays with names like Mother’s Letters to a Daughter on Woman’s Suffrage and books like Womanhood: Its Sanctities and Fidelities. Another page ripper! In other words, Harriet grows up in a clan committed to social justice. They held debates around the dining room table, and everyone—boy or girl—is encouraged to join.

We don’t know how much exposure she had to slavery as a child, but it wasn’t abolished in her home state until 1848—so she probably would have seen it. Some of her earliest memories are of two black women hired to work for the family, both indentured servants, and how they comforted her after her mom Roxanna died.

She and her sister Isabella enrolled in the school Catharine founded, the Hartford Female Academy, which will soon become one of the premier schools for young girls. There she studied subjects usually reserved for the gentlemen, like complex reasoning, philosophy, chemistry, classics and math. As we already know, Catharine felt such things would make one a much better wife. Which is funny, because Catharine herself never married, and apparently didn’t keep a whole lot of house. But it’s interesting, this thing about one of Harriet’s biggest female influences: she believes that there SHOULD be separate spheres, but that women’s sphere should be elevated—placed on a par in terms of respect and importance with a man’s. She is responsible for turning children into good citizens, with being good and well-informed pillars of their communities, and are basically in charge of public health. She didn’t believe in the vote for women, as it would just confuse things, but she DID help 19th-century girls who could afford it with a rocking education. So there’s that.

Catharine Beecher did not come to play. She came to mold young lady minds.

Wikicommons.

At school, Harriet meets some other future budding authors: Sarah P. Willis, for one. She’d go on to become one of the era’s most highly paid writers, using the nom de plume Fanny Fern, to talk about women's rights, domesticity, and the trouble with the patriarchy.

Harriet turned out to be a good teacher herself. By age 18, with Catharine gone awandering, she was practically running the place, and writing lots of essays in her spare time. But as we know from our travels with Clara Barton, and as I learned from being a full-time teacher and freelance writer for several years, being a teacher is far from easy. The pay is low, the hours are long, the number of students you’re teaching at once is outrageous. It’s exhausting. As one doctor said about the era’s teachers, “they wear out faster than any other class of people.”

Before the Civil war, some quarter of women born on American soil has been a teacher at one time or another. And we can thank Catharine Beecher, in part, for making public school education today a mostly female-dominated thing—for making it a place where woman could earn their own way, even if that way is hard.

a writer is born

Anyway, back to Harriet scribbling away in her off hours. At 21, she moves with poppa Lyman to the big city—Cincinnati, Ohio—where he is heading up the Lane Theological Seminary. It is a city with a booming trade courtesy of the Ohio River, with people sailing up it from all over the country to take advantage of work opportunities there. These included Irish immigrants and African Americans. A riot takes place between these workers in 1829, where push turns to blows as some Irish workers try to chase black workers away because they see them as unwelcome competition. Harriet tends to some of the wounded in these riots, which take place several times over the years, and in so doing gets to know some of the African American workers and their stories. Their stories won’t leave her in a hurry. They will grow, taking shape as something bigger: a story she wants to share with the world.

While there, she also spends some time in nearby Kentucky, where slavery is still very much alive and kicking. A plantation she visits there, called Shelby Plantation, will later serve as the model for the plantation in Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

But there are pleasantries in Cincinnati, too. She joins up with a scholarly group called the Semi-Colon Club (how much do I love a semi-colon? So very much): a literary salon where she chats with fellow members Salmon P. Chase, a guy who will one day be one of Abraham Lincoln’s advisors, and Emily Blackwell, one of the first American ladies to get a medical degree. I love thinking about these radical smarties sitting around discussing women’s rights and their views on punctuation!

It was while whispering over grammar that she falls in love with a widower named Calvin Ellis Stowe. A theology professor, she describes him as, bless: “rich in Greek & Hebrew, Latin & Arabic, & alas! rich in nothing else…” They get hitched on January 6, 1836, start having babies, and eventually move to a cottage near in Brunswick, Maine. If Harriet had someone’s else views and personality, our knowledge of her story would probably end there. But Calvin feels as passionately about ending slavery as she does, and he believes in his wife, who knows that she is meant to write something important.

But where to find the time? Harriet is busy having and raising seven babies, and doesn’t have a whole lot of room for writing masterpieces. Particularly when, as we know, 19th century men do not see it as their duty to help out much at home. You think women struggle to have a thriving career and raise a family now: we have it easy. Say you want to make a birthday cake, since in this era it’s not like you can run out and buy one: you have no baking powder and a brick of sugar to work with, which meant you had to HAND BEAT the batter WITH A FORK for 45 MINUTES. Are you ready to take a nap yet?

It doesn’t help that society doesn’t exactly encourage working mothers. That said, Harriet’s husband’s paltry income means she has to write as much as she can to help make ends meet. That’s the (extremely valid) excuse MANY female writers use in this era for having the gall to make money from their art: it’s to feed their family, so that makes it socially OK, right? She manages to write and publish her first novel, Mayflower, in 1843, despite the diaper changing and prolonged beating of cakes.

All the while, her great idea is brewing away in the back of her mind. She also continues to interact with the formerly enslaved—her husband and brother helped out at least one man escaping slavery on the Underground Railroad. She is horrified by the stories she hears, particularly of separated families. But one story influences her perhaps more than all the rest.

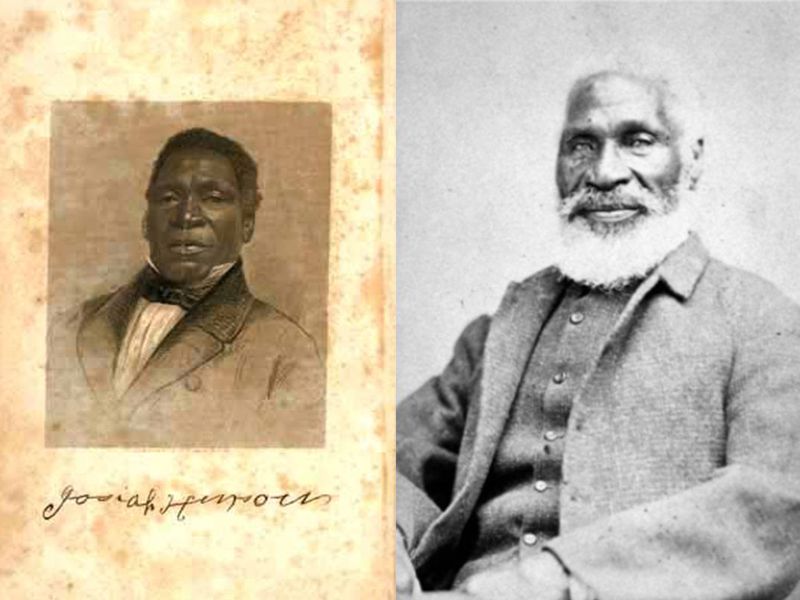

In 1849 she reads a memoir by Josiah Henson, a formerly enslaved man who just published the story of his life. His story becomes the backbone for Harriet’s novel. His earliest memory was of his father’s ear being cut off, then being sold south—all because he fought back against a white man who tried to sexually assault his wife. Things didn’t exactly go uphill from there. He and his mother were treated badly and whipped often, especially when Josiah made the mistake of trying to teach himself to read. Years later, when he’d risen up the ranks to become his master’s chief seller of produce at the markets in Washington, he started preaching around the city. Since he couldn’t read, he memorized verses by listening to them, making them his own. A white man he was friendly with convinced him to raise money to buy his own freedom, but his master stole it and tried to sell him south. Eventually, he escaped with his wife and two of his children—they walked 600 miles, all the way to Canada. That’s 11½ marathons. He went on to start a sawmill, which cut such good lumber it won a prize at London’s World’s Fair, and became an active stationmaster in the Underground Railroad.

But Harriet doesn’t just read his memoir—she asks to meet him. He said:

“We went to Mrs. Stowe’s house, and she was deeply interested in the story of my life and misfortunes, and had me narrate its details to her. She said she was glad it had been published, and hoped it would be of great service, and would open the eyes of the people to the enormity of the crime of holding men in bondage. She manifested so much interest in me, that I told her about the peculiarities of many slaveholders, and the slaves in the region where I had lived for forty-two years.”

That same year that Josiah publishes his memoir, something else profound happens to Harriet: the death of her 18-month-old son, Samuel. This devastating loss opens a window in this relatively privileged woman’s life into what it must be like to be a woman in bondage.“It was at his dying bed,” she said later, “that I learned what a poor slave mother may feel when her child is torn away from her.”

And then along comes the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. As we talked about in episodes 9 and 10, this law is deeply distressing and damaging—but it gives those feeling queasy about slavery a big push to stand up and shout about it. Harriet and her siblings certainly feel like shouting. They can’t believe the government would try to force them to participate in something as evil as slavery.

Harriet wrote to Catherine:

“It did my heart good to find somebody in as indignant a state as I am about this miserable fugitive slave business. Why I have felt almost choked sometimes with pent up wrath that does no good.”

Her sister Isabella, for one, thinks it’s about time Harriet writes something about the peculiar institution. “Now, Hattie, if I could use a pen as you can, I would write something that would make this whole nation feel what an accursed thing slavery is.”

THE BOOK

But how to get it written, with so many children to tend? “As long as the baby sleeps with me nights I can’t do much at anything,” she wrote, “but I will do it at last.” Luckily, she has some fabulous female family members to lean on. Isabella is the one that copied out the manuscript. Catharine actually moves in with Harriet and her family during the writing process, tending the children so Harriet can meet her daily word count. “I am trying to get Uncle Tom out of the way,” Catharine wrote. “At 8 o’clock we are through with breakfast and prayers and then we send off Mr. Stowe and Harriet both to his room at the college. There was no other way to keep her out of family cares and quietly at work and since this plan is adopted she goes along finely.”

It’s hard, but Harriet HAS to write it. “I feel now that the time is come when even a woman or a child who can speak a word for freedom and humanity is bound to speak,” she wrote to the editor of a journal called The National Era, which will eventually be the one to publish it. “I hope every woman who can write will not be silent.”

The first installment of Uncle Tom's Cabin appeared on June 5, 1851 in an anti-slavery newspaper called The National Era. And readers ate it up.

(Courtesy of the Harriet Beecher Stowe Center)

In 1851, Uncle Tom’s Cabin runs for the first time in The National Era, a Washington antislavery paper, with the subtitle "The Man That Was A Thing", which is soon changed to "Life Among the Lowly". Readers wait breathlessly for each week’s installment; there are 41 of them in all. To say that people are gripped is an understatement: the paper’s readership leaps up by 26%. You can imagine how quickly the book publishers came calling.

authoresses and the publishing industry

Before we talk about the novel’s contents, let’s talk about the publishing industry so we can appreciate Harriet’s triumph. With technology making printing easier and cheaper, the industry is changing fast. Steam-powered cylinder presses make it possible for thousands of newspaper copies to get churned out every hour. The railroad, steamboats and the telegraph mean that news can travel faster and farther.

So while most women live in rural towns, not cities, they have access to newspapers, mail-order periodicals and novels in a way they’ve never had before. Before the Civil War, Harper’s Magazine estimated that some four-fifths of their readership were women. By 1861, the country has about 3,700 newspapers in circulation—that’s twice the number published in Britain, and accounts for one-third of the world’s supply. Magazines have become way more popular, particularly with the ladies. Godey’s Ladies Book, filled with fashion plates and practical guides to domestic goddess-hood, is the Good Housekeeping of the century. Or perhaps the Cosmo of the century, minus articles with titles like “Ten New Ways To Rev His Engine Tonight”. As we talked about in episode 1, women of this age are clamoring for advice columns and how-to books about domesticity, and there are a lot of them. Victorian women are taught things like reading, writing, and math to equip them to be at-home teachers for their children, but it has another consequence: it makes them America’s first mass book buying audience. Particularly novels. I mean, men were too busy out making money to indulge in such things: if it’s not related to stocks or business, why bother? Women suddenly have a way of exercising an unprecedented consumer power.

And that also opens up opportunities for lady writers and editors. Sarah Hale, when she finds herself a single mother of five at the tender age of 40, makes money by staying up late and writing. Poems, mostly—you know, like that one about Mary’s little lamb, maybe you’ve heard of it? She becomes the first woman “editress” of a magazine written specifically FOR women. Later, she becomes the editor of Godey’s Ladies Book, which by 1860 has some 160,000 subscribers. She’s ALSO responsible for pushing Abe Lincoln into making Thanksgiving in actual holiday! Thanks, Sarah: we owe you one.

But life isn’t easy for women writers, who often write under a pen name just so they don’t have to face cries of their being unwomanly. Authoress Julia Ward Howe publishes a novel called Passion Flowers anonymously in 1853, after her husband threatens to divorce her and take the kids. He doesn't speak to her for three months afterward. And he is far from the only man to feel betrayed and outraged when his lady relation takes up her pen to express herself.

Despite the fact that women aren’t really encouraged to become authors, there sure are a lot of them in the 19th century—social reformers, abolitionists, spiritualists, and gals just wanting to write a captivating tale. Nathaniel Hawthorne famously complained this “damned mob of scribbling women” were ruining literature. This outburst may have been because he heard that one lady novelist’s book sold more copies in a month than his book The Scarlet Letter sold…well, ever. But come on, Nathaniel. I was forced to read that book in high school and it was WORSE than pulling teeth with tiny plyers.

Let’s talk about a few other awesome authoresses real quick. A few years before Uncle Tom’s Cabin, a gal named Susan Warner writes a book called The Wide, Wide World, which becomes one of the nation’s very first true bestsellers: it goes through 14 editions in just two years and becomes the first novel to reach the ‘one million books sold’ mark. It’s a lady novelist, Catherine Maria Sedgwick, who popularizes the Christmas tree in one of her stories. In 1862, Julia Ward Howe thought that a war anthem that Harriet Tubman particularly likes, “John Brown’s Body”, should have a more positive bent. So she writes the poem “The Battle Hymn of the Republic,” which quickly becomes the Union’s Civil War anthem.

Another jealous Nathaniel, who’s an editor over at Home Journal, looks down on what he calls the “universality of cheap and trashy novels”—mostly written by ladies—and how sentimental many of them are. And yes, even some lady novelists have to admit there are a lot of very emotionally OTT novels out there. It helps to understand what American readers are particularly obsessed with. On one hand, you have Charles Dickens ,with his sad orphans and their tales of woe. On the other you have Charlotte Bronte and Jane Eyre, haunting and passionate, which is particularly loved by American ladies because of how its plucky heroine brings a man to his repentant knees. But a lot of the novels of the time don’t necessarily follow that model. You have a lot of authoresses writing about sweet orphaned girls going through many adventures. But lady authors had to be mindful of the Victorian Ideal in the stories. Like Sarah Emma Edmonds’ favorite novel, Fanny Campbell, the Female Pirate Captain, these girls could go on usually boys-only adventures only under extreme duress—to rescue a man, or because they have no money, or because their wicked male relations abandon them. She must stay chaste and upstanding throughout the proceedings. And our sweet young heroine just has to get married and settle down in the end.

But Harriet’s is something different. It’s not really meant to be entertainment, and it’s not really about white women at all.

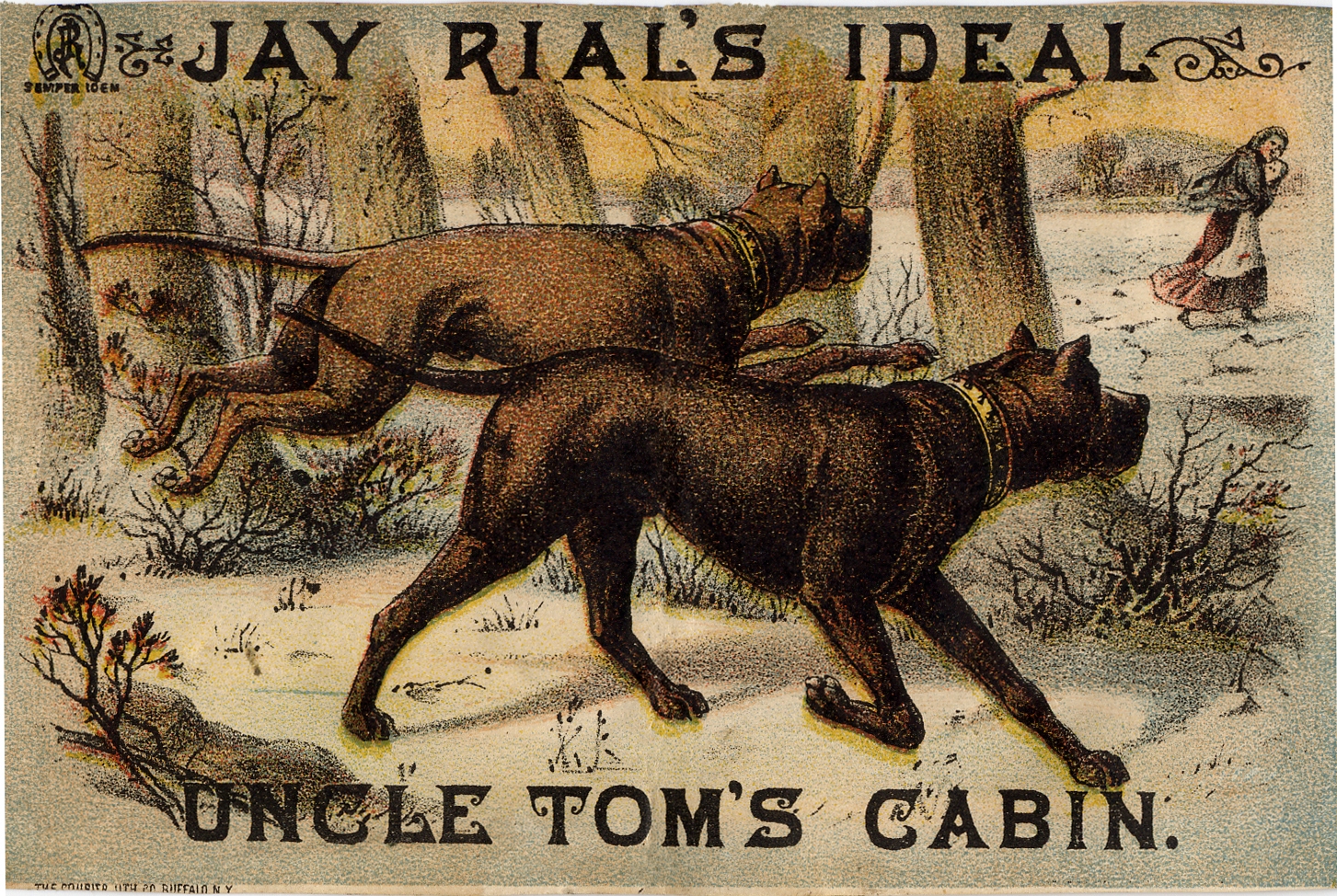

One of the many promotional posters for Harriet’s best-selling novel. (Wikicommons)

The story unfolds at the Shelby plantation in Kentucky, where two men—Tom and young Harry—are sold away to settle some family debts. The master’s wife has promised Eliza, her servant and Harry’s mother, that he wouldn’t be sold. But now he is, and the story splits down two different paths. On one, Eliza and Harry run away from the plantation, hopping over ice flows with Harry in her arms as her pursuers try to grab her. Eventually, her family is reunited in Canada. Tom decides to stay to protect his family and ends up deep down South. There, he meets a cast of characters: Eva, a kind white girl, and her passive father; Topsy, a young black girl who acts out to try and mask her sadness; and the harsh and cruel Simon Legree. He holds onto his faith throughout his struggles, but it isn’t enough to save him. Eventually, Legree beats him to death for refusing to give up the place where two runaway women are hiding: his cabin.

The genius of Harriet’s book is that she seems to know who her audience is: mostly women. And to get women to care, she plays on their emotions, putting the spotlight squarely on how slavery treats mothers and their children. The way it rips families apart. That scene where Eliza runs, desperate, across the river with her son, is as iconic as the one where Harry Potter faces Voldemort—even more so. Because this isn’t fantasy: it is real. The book peeled back the veil between North and South, showing northerners just how terrible things were for the enslaved. It made them realize, too, that just because they didn’t own slaves, that didn’t mean they weren’t responsible for what was happening. It was also meant to shake southerners out of their complacency: to hold up a mirror and make them look at, and feel, the effects of the system they continued to perpetuate. It shocks many people in wokeness. It was, as poet Langston Hughes put it, “America’s first protest novel.”

It is published in book form on March 20, 1852, and from day one, it’s a smash hit. The book sells 3,000 copies in its first day on shelves. By the end of its first year in print, that number has reached more than 300,000—and that’s just in America. It sells a staggering 1.5 million copies worldwide in that first year, becoming one of the first international bestsellers to come out of America. There’s a sharp rise in the number of mothers naming their babies Eva. By the end of the century, only the Bible will beat it out in terms of sales.

Muse Josiah Henson said of it:

“When this novel of Mrs. Stowe came out, it shook the foundations of this world… It shook the Americans out of their shoes and of their shirts.”

It shakes a lot of people—and in a world with slavery still at its center, it also strikes a lot of nerves. Antislavery pundits eat it up, and quickly. So does the fledgling Republican party, because years later, during the 1860 presidential campaign that Abe Lincoln will win, they hand out 100,000 copies to try and get abolitionists on side. And it seems to have helped. As radical Republican leader and Senator Charles Sumner said, “Had there been no Uncle Tom’s Cabin, there would have been no Lincoln in the White House.” It is one of those books that, if you haven’t read it, you are missing something.

Of course, not all Northerners love it. I mean, it was written by a woman, after all. A New York Times review says of it years later, “To use novels as weapons of attack or defense is like giving foul blows in boxing. You may disable your antagonist, but you degrade yourself, and doubly degrade the supporters who applaud you.”

Critics proclaim that it’s just propaganda—her portrait of slaver owners is unrealistic and unjust. “It left some of them on the sandbar barefooted and scratching their heads,” Josiah Henson said. “…so they came to the conclusion that the whole thing was a fabrication.” Southerners are outraged: they certainly don’t know any slave owners who behave like that. They keep their slaves fed and clothed—how dare she call them devils! And besides, it’s a novel. It’s all made up. Some of them even write response pieces meant to tell the REAL story about slavery, and they sell well. But not as well as Harriet.

That’s not to say Southerners don’t read it: boy do they. Our favorite Southern diarist MARY CHESNUT writes about it several times in her diary, though as is her usual style, she uses it as a means of musing on her own life, and the lives of southern plantation wives like her. “I hate slavery. You say there are no more fallen women on a plantation than in London, in proportion to numbers: but what do you say to this? A magnate who runs a hideous black harem with its consequences under the same roof with his lovely wife, and his beautiful accomplished daughters? He holds his head as high and poses as the model of all human virtues to these poor women whom God and the laws have given him….you see, Mrs. Stowe did not hit the sorest spot. She makes Legree a bachelor.”

And of course, critics say the thing people are STILL saying about works by female authors: ugh, the writing is just too emotional to be serious or worthwhile.

Did she curl up in a ball and cry about it? Nope. She snapped back. “I wrote what I did because as a woman, as a mother I was oppressed and broken-hearted, with the sorrows and injustice I saw, because as a Christian I felt the dishonor to Christianity — because as a lover of my country I trembled at the coming day of wrath. It is no merit in the sorrowful that they weep, or to the oppressed and smothering that they gasp and struggle, not to me, that I must speak for the oppressed — who cannot speak for themselves.”

She writes another book in 1853, called The Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin: Presenting the Original Facts and Documents upon Which the Story Is Founded, Together with Corroborative Statements Verifying the Truth of the Work. It points out all the ways in which her little emotional novel is indeed realistic. You best believe that bibliography was very, very long. She said, “The character of Uncle Tom has been objected to as improbable; and yet the writer has received more confirmations of that character, and from a great variety of sources, than of any other in the book.” Many of those confirmations came straight from Josiah Henson himself.

And you know who checks out that book and keeps it on his desk for 43 days? President Abraham Lincoln. He borrows it from the Library of Congress in 1862, at the same time he is writing the Emancipation Proclamation. We don’t know how much it influenced him, but that’s some pretty timely reading.

Some say that, when she went to the White House and met the great man, he said “So you are the little woman who wrote the book that started this great war.” The book itself didn’t light the match, for sure, but it certainly fans the flames—and thus helps change history.

Love it or hate it, it has an impact. Putnam’s magazine wrote, “Mrs. Stowe, who was before unknown, is a familiar a name in all part of the civilized world as that of Homer or Shakespeare.” In the Boston Music Hall, where abolitionists gathered to celebrate the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, they all chanted—what, you ask? “Abraham Lincoln?” Nope: “Harriet Beecher Stowe! Harriet Beecher Stowe!”

Harriet didn’t write the book to make money, she said; she just hoped to make enough money to buy a new dress. But by the end of its first year, she could have bought ALL the dresses. Sad to say, Josiah never made money from it. Years later, the book is turned into theatrical shows which are very popular…but, to put it mildly, they are in very poor taste. They feature white actors in black face portraying twisted caricatures of the book’s subjects: Uncle Tom—poor, with terrible grammar, and all too eager to sell out his brethren to win over his master—is what most people ended up remembering. It must be said that, despite her best intentions, Harriet’s book shows the protentional pitfalls of writing someone else’s story. She uses dialect freely in the book, sometimes in cringeworthy ways, painting her subjects in a pretty stereotypical, and offensive, light. And while she felt strongly that slavery was wrong, she didn’t necessarily believe that equality was the answer either. She thought, like many people, that perhaps they should be shipped back to Africa—that they could never find true freedom in America, amongst people who were intellectually superior to them. And therein lies her complication multitudes: though she was responsible for profound social change, she also didn’t believe that black people were, by nature, her equal. It’s hard for us to understand now, but believing so would have made her WELL ahead of her time. But it’s worth remembering that this was a very racy book for her to publish—dangerous, even. She took a huge risk, because she felt it was her responsibility to fight.

later life

Harriet goes on a huge lecture tour to meet her fans. Remember, this is a time when women up on stage speaking on serious topics is scandalous in the extreme. So Harriet allows her male relations to speak for her, voluntarily stowing herself away backstage. “I have been forced into it,” she told a fan about her speaking tour and her general famousness. “Contrary to my natural modesty.”

After the war, Harriet goes on to become one of the first editors of Hearth and Home magazine, a women’s mag, and campaigns for the expansion of married women's rights. As she grows older, she isn’t afraid to make bold statements. Like when she says in 1869, rather racily:

“[T]he position of a married woman ... is, in many respects, precisely similar to that of the negro slave. She can make no contract and hold no property; whatever she inherits or earns becomes at that moment the property of her husband.... Though he acquired a fortune through her, or though she earned a fortune through her talents, he is the sole master of it, and she cannot draw a penny....[I]n the English common law a married woman is nothing at all. She passes out of legal existence.”

She has a lot of fascinating things to say about womanhood, in fact—things that feel fresh to us even today. Like this gem about body image:

“We in America have got so far out of the way of a womanhood that has any vigor of outline or opulence of physical proportion that, when we see a woman made as a woman ought to be, she strikes us as a monster. Our willowy girls are afraid of nothing so much as growing stout…”

She and her husband used some of the money to buy an orange grove in Florida. As you do. She loved the weather there, though even thinking about Florida makes me sweaty, and the family spent winters there until Calvin’s health was too bad to allow it.

Otherwise, she lives in Hartford, Connecticut, and continues to write, ultimately producing 30 books and novels. She goes on lecture tours, advocates for education initiatives, and generally continues trying to make the world a better place.

But what happened to Josiah Henson? He may not have made it rich with the novel, but he does use the book’s wild success to do all he can. He publishes his memoir again and uses the proceeds to buy his brother’s freedom. He supports families who had loved ones join up in the Union army, and ran businesses that created jobs for African American refugees. He goes on a speaking tour at age 87, during which he met Queen Victoria. And while he does all of that for himself, for sure, Harriet played her part in it.

“From that time to the present, I have been called ‘Uncle Tom,’” he said. “…and I feel proud of the title. If my humble words in any way inspired that gifted lady to write… I have not lived in vain; for I believe that her book was the beginning of the glorious end.”

American teens all learn about Uncle Tom’s Cabin in school, but we don’t generally read it. It hasn’t become a Crime and Punishment or a Wuthering Heights. But Harriet Beecher Stowe’s work was more than a classic: it was revolutionary, helping to shape the public conscious for decades to come. And that will always make it a kind of masterpiece.

music

“Ho Hey” by Loco Lobo, from Freemusicarchive.org. All other music and sound effects from Audioblocks.com