The Hair Down There: The History of Our Relationship with Lady Jungles

One of the most intense dinner party debates I’ve ever had was over the issue of a lady’s pelvic jungle: specifically, whether or not we should be taking it off.

Someone had a friend who’d just spent a huge amount of money to get her entire downstairs carpet lasered off: a present to herself, it was said. I couldn’t help but push back: but why, I asked. Was she really doing it for herself or for the pleasure of others? Why should women feel compelled to go bare? Everyone had a different and strongly-held opinion: social pressure, a partner’s preference, self-gratification, the idea that perhaps our hair is just gross. And while I’m not a complete stranger to a Brazilian wax parlor, something about the conversation bothered me; I didn’t like hearing smart, confident women say they didn’t feel as sexy without a good trim. Why did we feel so compelled to DO something about such a natural part of us? And why did the issue feel so charged?

This debate, and practice, are far from new. We’ve been getting rid of our personal shag rugs for millennia, across many cultures. And it turns out the decision to wear it or bare it has always been complicated, tied up in cultural belief, social norms, and personal hygiene. And it’s about a whole lot more than aesthetics: particularly when we’re talking about women, the issue is a lot more complicated than I knew.

So let’s take a journey through time, tracing the history of pubic hair removal from ancient past to present, exploring our relationship with our lady jungles and what it might have to say about our feelings about ourselves. Joining us is a woman who has spent a lot of time thinking about and researching this issue. “I'm Lindsay Craig. I am a grad student at the University of Nevada Las Vegas in the Department of Anthropology and I primarily study women's sexual signaling…” The seeds for her interest in pubic hair removal goes back to her undergrad psychology days. “I got my undergrad in developmental psychology and my group and I would sit around and talk about women's issues in this very feminist group, and we talked about pubic hair and how a lot of people said that women remove their pubic hair because it's a male dominated society and that's what men want, and that's what is shown in pornography, and that's what product marketing is trying to do is get us to buy their razors and remove our pubic hair.” And when her anthropology grad advisor suggested this issue was ripe for study, she wanted to see if those hypotheses from her lady’s group held true.

She sifted through written records from the 1890s to the early 2000s, surveying nearly 200 societies around the world. The goal? To figure out how our pubic hair removal practices differ from era to era and culture to culture, and why we perform them at all. The results of her study might just make you rethink your relationship with what you’ve got going on below the belt.

Grab a razor, a handful of shells, and a snuff box. Let’s go traveling.

come on, minions. let’s wax me.

Liz Taylor playing the late, great Cleopatra VII Philopater.

MY sources

LYNDSEY’S STUDY

"Pubic Hair Removal Practices in Cross-Cultural Perspective." Lyndsey Craig and Peter B. Gray. Cross-Cultural Research 2019, Vol. 53(2) 215–237 © 2018 SAGE Publications.

BOOKS

The Oxford Companion to the Body. Oxford University Press; 1 edition. Colin Blakemore (Editor), Sheila Jennett (Editor). Feb. 2002.

Encyclopedia of Women in the Ancient World, Joyce E. Salisbury. ABC-CLIO, May 2001.

Plucked: A History of Hair Removal. Rebecca Herzig, NYU Press, Nov. 2016.

Encyclopedia of Hair: A Cultural History. Victoria Sherrow, Greenwood, Feb. 2006.

ONLINE

A great video on the subject, which is a fun companion to the podcast episode: The Evolution of Pubic Hair, MindMapped, YouTube July 2017.

"The History of Body Hair Removal." The Women's History Museum.

"Pubic Hair Trends Over Time" by Gabrielle Moss, Bustle.com, Nov. 2014.

"The Sneaky, Manipulative History of Why Women Started Shaving" by Marlen Komar, Bustle.com, Dec. 2016.

"Gentlemen, Charge Your Indecent Props!” By Tony Perrott, Slate.com, Dec. 18 2009.

“Emanscapation: Between the Public and the Pubic in Ancient Greece.” Angele Rosenberg, Medium.com, Nov. 2015.

“Victorian Feminine Ideal.” by R.S. Fleming, Kate Tattersall’s Adventures, Oct. 2013.

“Did Renaissance Women Remove Their Pubic Hair?” Jill Burke’s Blog, Dec. 2012.

transcript

please forgive any typos: this was originally meant for an auditory format and sometimes I miss things.

Let’s start with something I’ve always wondered. Why do we even have hair down there? What’s its purpose?

We used to be quite hairy creatures, but over time we dropped a lot of our furry covering—though strangely, not our connubial fringe. We’ve come up with a few hypotheses about why, evolutionarily speaking, this might have happened. One is that our below-stairs hedges are an indication of sexual maturity: a sign that we are, in essence, of age to mate and reproduce. Back when we didn’t wear a whole lot of clothes, our bushes could send quite a powerful social signal. And as we’ll see in some of the anthropological work Lyndsey pored over, it has continued to. Another theory is that it traps pheromones: chemicals that trigger sexual attraction. Our pubic hair hangs onto these scented beauties, beckoning sexual partners to come on down to lady town. Our hair is also supposed to ease friction during bouts of horizontal tennis and help protect us from unwanted pathogens. We now know that having no hair whatsoever actually exposes us to sexually transmitted diseases because of the likelihood of cuts and abrasions from trimming, but it does keep us from getting pubic lice. YES, you heard me: PUBIC. LICE. Otherwise known as crabs, which will not kill you, but are not something anyone’s going to line up for.

There’s also the idea that our downstairs drapery is there to keep us warm – a theory I seem to have heard more than any other – but that doesn’t explain why we dropped most of the rest of our body hair. What we can be fairly sure of is that it’s meant to protect us in some way, though these days many of us find it more hindrance than help.

TENDING TO THE HEDGES: A HISTORY

So how did ladies of the past feel about their lady jungles? Let’s take a time-hopping survey, starting all the way back in ancient times. As we’ve learned in Season 2 already, many of the ancients liked their pubic hair best when it was no longer attached to their bodies. If ancient art is anything to go by, not a lot of women in some of the better-known civilizations were walking around with a mighty netherforest. For instance, we’ve found Paleolithic lady figurines with lady parts completely exposed: no hair to be seen. And while that might have just been a stylistic choice on the part of the artist, we have plenty of evidence that ancient civilizations took hair off whenever possible.

Some of the world’s first razors and tweezers are invented and used in ancient Egypt. Egyptian men and women alike remove much of their body hair, including their muffs, by scraping it off using sharp pumice stones, flint, and early forms of hair removal cream. Cleopatra may have sloughed off her regal fringe using a sugar mixture, which would then be ripped off with strips of cloth in a practice not all that different from modern-day waxing.

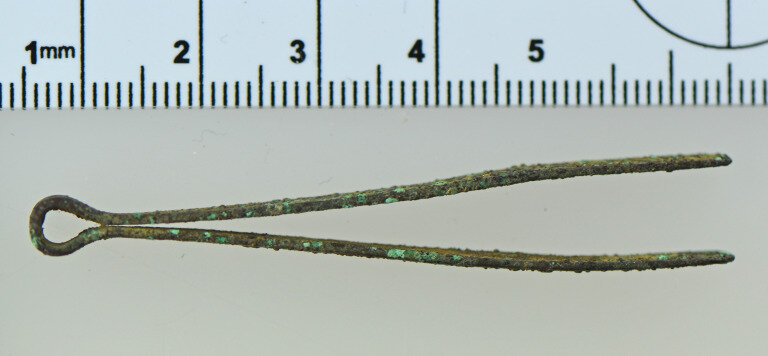

Ancient Egyptian tweezers. we’ve been removing hair from our bodies for a very long time.

Courtesy of the National Museums Liverpool.

Ancient Greek women may be fans of a bushy eyebrow, but not of hair below the waist. Ancient Greek plays from the Classical period suggest that women trim their hedges quite regularly and that it is very much a feminine activity. In one of Aristophanes’ plays, a man decides he’s going to dress up as a woman to try and spy on a lady mob, only to have his friend strap him down and make him remove all his pubic hair: an effeminizing exercise, and what the traumatized man thought was a little over the top. Look at any statue of a Grecian goddess and you’ll see very little evidence of a pubic jacket, suggesting that male artists think a smooth and hairless field was the sexy feminine ideal.

Because they consider a bush uncivilized, ancient Greek ladies remove it by singeing and plucking. Upper-class Roman women take care of business using tweezers, pumice stones and depilatories, while women in ancient Persia use early hair-removal creams. In ancient Rome, how much hair you have down there becomes a symbol of status: the less you have, the fancier you are considered. Given how frequently they go to public baths, I’m guessing this is a major subject of gossip in the change rooms.

i’ve plucked more than just my unwanted facial hair.

Aphrodite of Cnidus by Praxiteles of Athens, Wikicommons.

By the time we get to the Middle Ages, our attitudes about pubic hair are changing. While some still take it off—this is a pretty dirty era where pubic lice are a real and understandable worry—the general trend is to leave it bushy. But again, we see pubic hair becoming charged with social meaning, as shaving it all off is associated with prostitutes. Therefore ladies of a certain standing are less likely to go bare.

Some women shave off their natural bush only to put on a merkin: a fluffy wig for your lady palace that first shows up in the records in 1450. I’d love to say this is inspired by a desire to redecorate, but apparently these artful creations are used to cover up sores caused by syphilis and gonorrhea. How delightful!

In the Elizabethan era, we don’t think ladies remove much of their body hair. Why bother when you’ve got on such a cumbersome number of layers? But the great Queen E DOES popularize one hair removal trend by savagely plucking her eyebrows and the front of her hairline. A long forehead was very much the thing.

big forehead, lead face paint, scanty eyebrows… I’m into it.

A young Elizabeth I portrait, Wikicommons

Regardless of your stance on ladyscaping, history offers plenty of recipes for the woman looking to remove her hair. Many of them are quite horrifying. Take this hot tip from a 1530s book called How to Remove or Lose Hair from Anywhere on the Body: “Boil together a solution of one pint of arsenic and eighth of a pint of quicklime. Go to a bath or a hot room and smear medicine over the area to be depilated. When the skin feels hot, wash quickly with hot water so the flesh doesn’t come off.” Melting flesh? Sign me up!

On average, and particularly in the Western world, it seems that shorn slopes are historically more popular with the upper classes: a signifier of cleanliness and class. But that’s not to say that, once removed, our lady hairs can’t still serve a purpose. If you’re wondering why we’ve gone time traveling with a snuff box, you’re about to find out. In 18th century pre-Victorian Britain, fine ladies often give their pubic hair to their lover as a sexy little souvenir. Men sometimes wear it in their hats to give them an extra dash of virile potency. The president of a sex appreciation club called The Beggar’s Benison wore a wig supposedly made entirely from pubic hair, first made in the 1600s out of hairs from King Charles II’s many mistresses. Years later, it is stolen by a member and made part of a new sex club, where members are asked to kiss the wig AND contribute to its growing fullness by adding in clippings from their mistresses. In compensation for the Beggar’s Benison’s wig loss, King George IV gets into the pubic hair gifting game in 1822 by gifting the club a locket of his own mistress’s trimmings in a silver snuff box. What all these ladies thought of their lady forests being turned into wigs and things is…hard to say.

In the West, as we start covering up more of our bodies and making anything to do with them morally suspect, it seems that we start shaving less. While unwanted facial hair is definitely something Victorian beauty guides and advertisements target, there isn’t a lot of mention of leg or armpit hair, not to mention anything down below. 19th-century Victorians are characteristically quiet about this particular issue. But while statues of the era tend to show bare mounds, keeping in the Classical style, saucy photos from around the Civil War era and after suggest that hair down there is often trimmed, but not always taken off entirely. And there is also a fair amount of slang for a lady’s lower fringe floating around during this era: thatched cottage, mossy cave, gooseberry bush, tail feathers, and my personal favorite: nether whiskers. Their very existence suggests that ladies are leaving their low toupee alone. But in America and Britain, a growing yearning to be tres European is introducing spa culture to the wealthy masses. Those with the money to afford it travel to Europe, where they discover the joys of a Turkish bath. There they are way more likely to give a belowstairs wax a go.

As a rule, Victorian women are very keen to keep long, lustrous locks up above, but the presence of certain commercial items suggests they are removing at least some of their body hair. An early version of safety razors first show up in the 1840s and seem to be quite popular, though author Lola Montez advises against using them. In her book on beauty from 1858 she suggests:

“Spread on a piece of leather equal parts of galbanum and pitch plaster, and lay it on the culprit hairs as smoothly as possible, and then, after letting it remain for about three minutes, pull it off suddenly, and it will be quite sure to bring out the hairs by the roots, and they will not grow again.”

Whether she meant this remedy to be used between our legs is hard to know.

Though you’d think that pubic hair removal would stop mattering so much when you aren’t showing it off except in the marital bed, particularly in an age when many women aren’t ever getting all the way naked there. And yet it seems that many gentleman prefer a neatly pruned forest. On his wedding night in 1848, art critic John Ruskin is said to have been so repulsed by his new wife Effie’s body that he refused to consummate the union. Effie Gray wrote of the interlude, “he had imagined women were quite different to what he saw I was, and that the reason he did not make me his Wife was because he was disgusted with my person.” Poor Effie! We don’t know for sure what prompted Ruskin’s reaction, but we’re pretty sure it was the traumatizing reality of her pubic hair. Perhaps ancient Greek statues gave him the wrong impression.

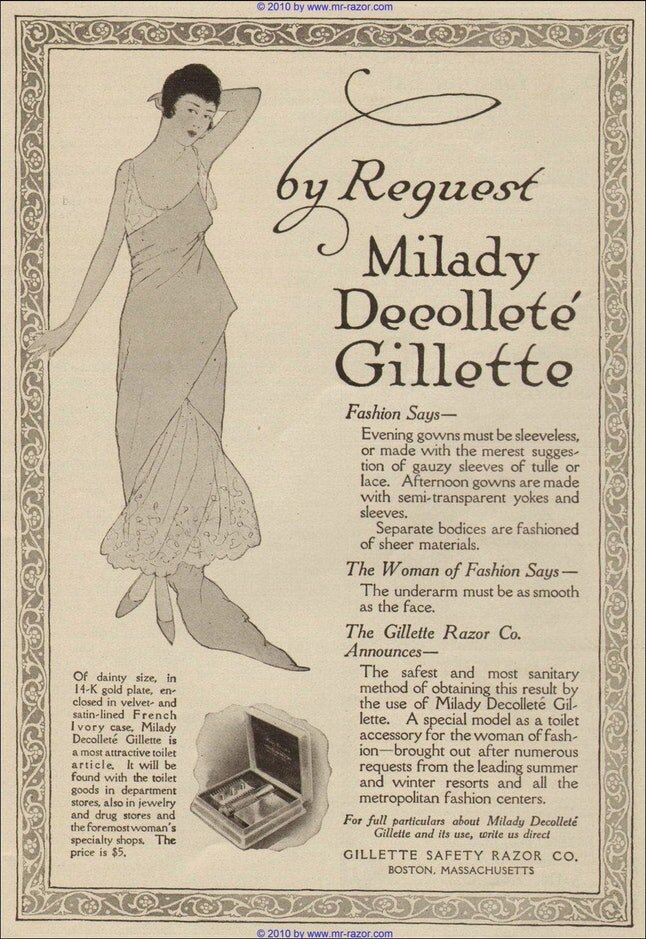

The first widely available body hair safety razors marketed to women finally arrive in the 19-teens. Though the commercials that come with them are mostly focused on armpit hair, inevitably women take them to whatever hair they want to get rid of. It stands to reason that as hemlines come up in the 1920s, along with a fashion for flapper dresses, no sleeves, and late night bar top dancing, more women start shaving. Though of course, this isn’t just about women deciding that body hair is not suited for public consumption: product marketing has a major part to play. A guy named, I kid you not, King Camp Gilette revolutionizes the safety razor with an inexpensive disposable blade of stamped steel.

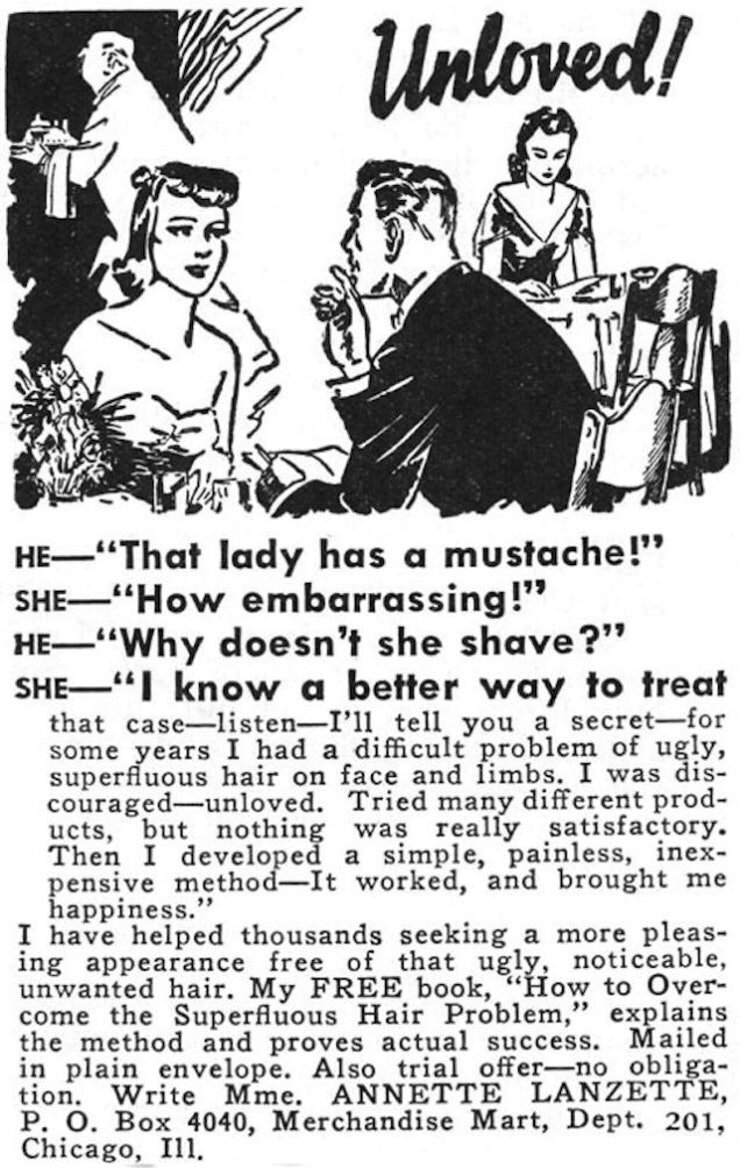

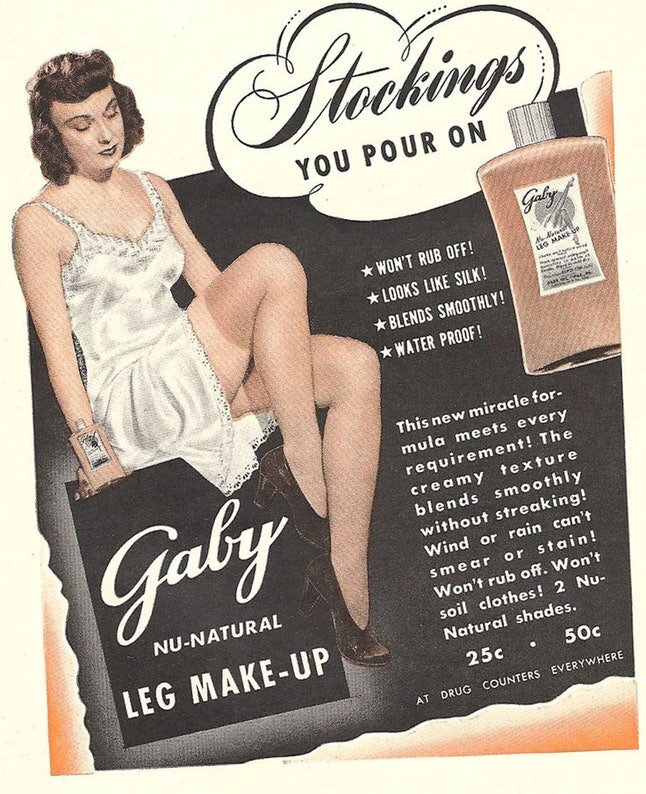

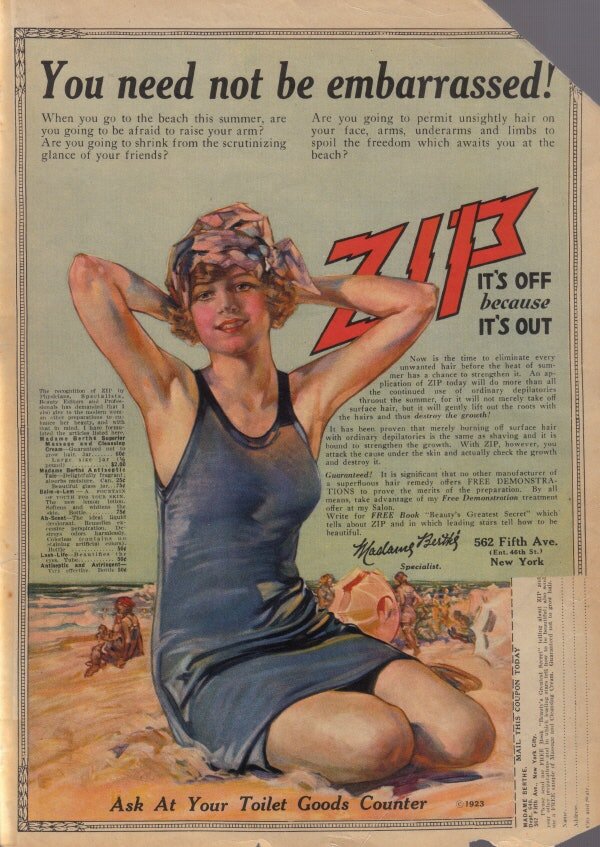

In 1915 he debuts his Milady Décolleté razor, making sure to advertise it as a female necessity: I mean, ladies, with these swiftly changing fashions you wouldn’t want to let any armpit hair escape, would you? It becomes linked with changing fashion: popular catalogues of the day, like Sears Roebuck, made sure to place ads for razors and depilatories in 1922 just when they started selling dresses with sheer sleeves. Razors are so linked with masculinity, though, that companies need to think hard about how to make it seem like a feminine necessity. The answer is two-fold: link it with good breeding - “classy ladies ALL shave their armpits!” - and associate not doing it with shame. In more and more ads, we see slogans like “no need to be embarrassed” and “are you going to spoil the freedom which awaits you at the beach?” Is this a consumer-driven marketing situation or a market driving women to shave? A chicken and egg situation to be sure. During World War II, with nylon scarce and women encouraged not to wear them, leg shaving becomes more popular. With bathing suits getting ever smaller and the bikini cropping up in the 1940s, razors become more likely to be applied to our personal parts as well. It doesn’t help that men go off to fight a war and take spicy pinups like Betty Grable with them, sporting teeny little bathing suits and noticeably smooth stems. Morale is low, ladies: shaving your legs is patriotism! Plus, nylon and silk are needed to make parachutes and such, so wearing stockings is no longer an all-American appropriate activity. You COULD wear what are called liquid nylons: a kind of leg paint made to mimic stockings, except they don’t really work unless you shave your legs. "The best liquid stockings available will deceive no one unless the legs are smooth and free of hair or stubble,” one ad advised. “Leg makeup will mat or cake on the hairs and make detours round the stubble.” After painting, you then have to buff it and dry it: some ladies would even draw on a little panty seam to make it look like the real deal. That’s a lot of work. So is it any wonder most women just decide to go bare?!

The 1960s and 70s bring ideas about sexual liberation to some of the Western world, which makes a fuller bush and hairy armpit much sexier than it may have been. The cool kids are definitely doing the “70s bush” look, leaving it all in its natural state – but of course, that’s not everybody.

And then comes the Brazilian wax, brought to you in the 1990s by the ladies at J Sisters salon in Manhattan. By the 2000s, people are proclaiming the death of the lady bush. Sex and the City, super low-riding jeans, everyone wanting to be tan and beach ready: our downstairs hair is declared unfit for service. But that’s changing again even now.

Of course, we’re mostly talking about the Western world here, which is only giving you half of the story. In non-Western cultures, pubic hair has also played a role: it even gets mention in some cultures’ mythology. These stories tend to center around a woman’s pubic hair specifically, showing her ripping bits of it out to do some sexy magic. Here’s Lyndsey with a story about the Kogi people in South America. “So the Kogi have a creation myth where their creator, who they call the Mother, removes her pubic hair and plants it in the earth, which then grows into penises. And from then on, all the men had penises. That's my favorite because it's sort of a reverse of what we have in our Christian/Catholic faith with Adam and Eve and the rib bone.” Other myths include one from the Waraonear modern-day Venezuela, who have a story about a woman using her downstairs hair to create a magical barrier by jerking it out, throwing it onto the ground and shouting, “Be thorns!” Less mess than pepper spray and just as effective! Here’s Lyndsey with a few other mythological gems for us:

“…one boy used his sister’s pubic hair to create a bow string; a man used his mother’s pubic hair to create a noose. So there’s this connection with pubic hair and women, and I think it is because pubic hair is such a strong signal of reproductive age for women. I think that’s why there is such a connection with sexuality.”

Our pubic hair removal practices have changed from culture to culture and year to year. But one thing has remained fairly constant: in most times and places, woman are way more likely than men to get all tangled up in the issue of whether or not to trim the hedges. And our relationships with our personal jungles are more layered than you might expect.

A STUDY IN LADYSCAPING

To conduct the study, Lyndsey searched through the eHRAF (Human Relations Area Files), an online database containing ethnographic data from 300 different societies around the world. “They just have this rich ethnographic data on all of these societies and you can actually use keywords, kind of like a Google search for ethnographers. And so I typed in pubic hair...” And then she had to sift through the data in an act of dedication that is the reason I worship historians and researchers: they’re the ones who do the hard yards. I just give the stories shape. “But the hard part was then going through and reading these ethnographers and finding the context in which they mentioned pubic hair and if they actually talked about pubic hair removal or retention as opposed to just talking about pubic hair as I like it like in their mythology.” And of course trying to dig up such an intimate issue had other challenges. “… the data that I used is over 100 years old in some cases. And the people who are writing, these ethnographers were European white men for the most part, so I'm sure there were a lot of challenges with asking women and men about their pubic hair.” A lot of the data was observational—a subject discovered in the field rather than sought out—but still, it was also very revealing.

Let’s start in the West. Shorn fields are the norm: a 2014 university study found that about 89% of women did some form of pubic hair removal, compared to 65% of men. That same study found that 49% of women took it ALL off, while only 18% of men did the same. A nationally representative US study done in 2016 found that, in adults aged 18 to 65, 84% of women removed at least some of their hedges, compared to 66% of men. Studies in the UK, New Zealand, Australia: all with just about the same results. And a lot of the results seem tied to age and level of sexual activity. In the West, very young women and post-menopausal woman are much less likely to do any ladyscaping. The more sexually active you are, the more likely to get out the shears.

Lots of things have been cited as potential motivators for pubic hair removal: pornography and product marketing are among them, for sure. A 2010 study that looked at Playboy centerfolds from 1953 to 2007 showed lady bushes getting progressively smaller, and then disappearing entirely, as the years went by. We’re also dealing with shifting social norms, and the feeling many have that downstairs hair just isn’t very sexy. Recent studies do suggest that marketing, pop culture, and pornographic movies all contribute to teaching women that their lady carpets are unfeminine, unclean, and unattractive.

“I do believe that pornography and product marketing and just culture in general has a significant impact on the way we experience our own bodies and our attitudes towards our bodies, but what my research shows is that it’s not just that: there’s something else going on.”

A 2014 study suggested that both men and women in the West tend to prefer at least some hedge trimming, though men are more likely to want their partner to take it ALL off. Studies show that some men actually find it disgusting, and we’re not entirely sure why this is. It could be that, given the imagery floating around on the internet, they’ve been conditioned to expect a shorn slope. It could also be instinctual. Our human disgust reflex responds to any perceived threat of infection, and so it could be an evolutionary response to pubic lice and other hair-down-there disasters. In an online study from 2016, heterosexual men who rated as particularly disgust sensitive had a significant preference for a partner with no pubic hair whatsoever. Lyndsey says one of the most popular theories on this issue is that complete removal makes the vulva more visible, which is why more men might be attracted to that. And though there isn’t quite so much research on men and their forests, studies suggest that homosexual men tend to trim or remove all their pubic hair more often than heterosexual men: their numbers are more on par with women.

While some studies suggest that women feel pressured to remove their pubic hair for a variety of reasons, the overwhelming motivation cited for trimming the hedges is personal: to have better sex, to feel cleaner, and just for overall emotional wellbeing.

Meanwhile, in non-Western countries, women are STILL much more likely than men to remove it. Lyndsey’s study found 26 societies, primarily horticulturalists, hunter-gatherers, and other pre-industrial subsistence cultures, that explicitly reported removing their pubic hair, and women were mentioned more frequently than men. The difference is that while the West cites disgust or social expectations as primary drivers, the non-West is more strongly motivated by health concerns. In one anthropological study, Lyndsey found a story from a woman who complained about her muff getting moldy because it didn’t get the chance to dry all the way after washing. And that is something nobody can get on board with. “…in the West and in non-western societies the most common reason for removal is hygienic. But in Western culture they talk about feeling cleaner if they remove their pubic hair. But when they do, the non-western societies talk about pubic lice or disease or pathogens. They actually talk about the physical hygiene rather than just a sense of feeling clean.”

In non-Western societies, another driver for removing a lady’s netherforest is to show the community that she’s reached sexual maturity. Even though puberty is when you actually start growing hair, taking it off sends a message that you’re ready to marry and have babies. Now that we’ve finally started growing it, let’s take it all right off, shall we?

They also claim unsightliness as a pretty common reason for wanting to give pubic hair the chop: many studies suggested that community members found a full bush unsightly. Though not everybody’s down with this view. In a 1980s study, the Kwoma of New Guinea said that the “thickest and most luxuriant” lady carpets were considered a mark of female beauty. A 1960s study showed that men of the Igbo society were suspicious of a woman with no pubic hair. It’s a punishable offense they associate with promiscuity: pubic hair won’t grow if a woman has frequent sex.

“…there were nine societies that specifically retain their pubic hair, and in one case a man was trying to choose between two women, trying to choose a wife, and he decided on the one woman who had the most luxurious pubic hair. And so she was his ideal woman because she had the most...”

In other societies, the ideal women had NO pubic hair. So even in places where health concerns seem to be a top motivator, it’s certainly not the only one.

It turns out the state of our hedges can tell our community a lot about us. It serves as a kind of social signifier, offering up information on our sexual and reproductive states. In a 1980s study, the Shona in Africa told a specific story about who removes what and when: young women removed their hair when they were sexually mature and ready to marry. But if a couple lost a child, they had to let their hair grow out as a sign of mourning, a period during which sex was off the table. Then, when the mourning period was complete, they would mark the occasion by shaving each other’s sexual jungles in a social ceremony, suggesting they were ready to become sexual beings again.

The biggest difference Lyndsey found between Western and non-Western societies practicing pubic hair removal was that the non-Western countries didn’t ever reference pornography or product marketing as a motivator. So again, we see that the images we splash about our public consciousness is not the only factor responsible for what we do with hair down there.

In terms of method, Westerners tend to shave or wax, mowing down that lady lawn with brutal efficiency. But in non-Western countries plucking reigns supreme: fingers and makeshift tweezers are the most common methods, though others are more creative. The Marquesas of Polynesia used shells; the Tapirapé in South America used bamboo; others used a bit of fine ash and their fingers. Sometimes we even have friends help us out. “The interesting thing about plucking your pubic hair is that it's very difficult to do yourself. You have to have somebody else to do it, and so it often involved a group of people.” Instead of drinking Negronis, let’s clear each other’s bikini lines! With shells! That sounds like an adventure.

the friends who pluck each other’s bushes with shells are friends forever.

Some societies in the study had very particular rules about methods of pubic hair removal. With the Amhara in Eastern Africa, religious doctrine stated that men should remove it by way of a razor and women by way of tweezers: to do the reverse was quite taboo. But once European razors made their way onto the scene, women started shaving and men stopped trimming altogether. So globalization has a part to play, too.

San women in Southern Africa had their pubic hair plucked out by their husbands, while the Tapirapé women removed their husbands’. In some societies, those of lower status were the ones doing the plucking. For men in another society, who plucked who was a matter of status. Men of higher stations would have their hair pulled out by a man of a lower station: a very intimate form of power move.

And so we see that our downstairs grooming habits can be many things: a sign of status, but also a potential bonding activity. It makes sense, if you think about it, that this might prove a way to bring ladies together. It’s an intimate thing, and a sign of trust, to allow someone to rip hair off such a sensitive and powerful region of our bodies. Perhaps doing it with friends even makes more sense than paying a stranger: for whatever amount of time you spend at the parlor, the person you pay to pour wax on your unmentionables has you entirely in their clutches. Think about THAT next time you get something waxed.

IT’S COMPLICATED

Here’s the truly fascinating thing that Lyndsey found…while men and women may both tend to their hedges in both Western and non-Western societies, across the board women are doing it more often. And the reasons why we do it – and our relationship with our sensual carpet – is very different on the whole than men’s.

The research suggests that when men trim, it tends to be for practical reasons: to prevent disease or just because it gets in the way of things. Lyndsey gives us an example from the Bakairi, who live in the South American Amazon:

“…in one case the boys after their first erection. They would then start tying their penis up against their abdomens with a cord but they would remove the pubic hair because it would. They didn’t want their skin to get irritated and get diseases or blisters from their pubic hair...it’s just a practical concern.”

But for women, the issue is a whole lot more loaded. Our lady jungles isn’t just a patch of hair. They are tied to our feelings about our sexual selves, our identity as sexy creatures, our feelings of attractiveness, self-confidence, and ourselves as reproductive beings. We even find this difference embedded in language. The Ingalik up in the Arctic region have gendered words for pubic hair: while men’s pubic drapery is called simply “crotch hair,” a woman’s is called “women’s sex organ hair.” A physical reality versus a sexual signifier. The studies bear this out, showing that sexual activity and maturity influence a woman’s decision about what she should do with her bush. In one study Lyndsey found, a woman only stopped removing her pubic hair when she was post-menopausal. “She was like I don't have to remove my pubic hair anymore because the men aren’t interested in it, in me anymore. So I don't have to worry about it. I don't have to care about it.”

Our lady jungles can serve as a powerful social signifier. But most societies aren’t walking around in the buff, you’re thinking: so who is my bush supposed to be speaking to? Lyndsey’s study posits that female pubic hair removal practices might signal our sexual receptiveness in long-term relationships, kind of a little a teeny “open for business” sign. It can also be a potent self-signifier: a way to tap into our own sensuality by, quite literally, bearing our wares.

CONCLUSION

When I first came to this topic, I thought it would just be a bit of fun: a risqué history to make us all break out our fans. But with all things women’s history, and related to a woman’s body, it turns out that our relationship with our lady jungles is far more complicated than I ever imagined. For us, our hair is layered in meaning: tangled up with our feelings about our sexual identities. My takeaway is this: no matter what your preference – an Amazonian jungle, a tightly pruned English garden, or a smooth and treeless peak – we should celebrate our choice and make it because it’s what makes us feel more comfortable. No matter what look you wear, we should always do it proudly.