Women in Tudor England: Fashion with Anne Boleyn

The queen of England washes her face and hands in a basin.

She lets her ladies in waiting remove the clothes she slept in and help her slip into a finely woven linen smock. What will she wear today, she wonders? It isn’t a trifling question. For Tudor women like her, dress is a kind of language, of symbols and meaning. In a world where she is supposed to be meek and submissive, fashion gives her a powerful voice.

For a queen, clothes aren’t just clothes. What she wears sends a message – sometimes several – to the eyes that are always on her, watching. It expresses her opinions, showcases her alliances, broadcasts her favor – or lack thereof. They are her magnificence, her right to power, made manifest. And Anne Boleyn needs all the power she can get. When King Henry VIII divorces his first wife, Catherine of Aragon, marries Anne, and kicks off the Church of England, it has ramifications that rock England to its foundations. There are plenty of people who see Anne as a false queen. Never did a royal woman need to think harder about dressing to impress. In the fight to hold on to her crown, the court is her battleground, her outfits her armor. So let’s suit up.

Today we’re time traveling with Natalie Grueninger, author of many books on Anne Boleyn and Tudor England, and the host of the wildly popular podcast Talking Tudors.

Grab your finest silk stockings and your most daring French hood: let’s go traveling.

sources

Books & Scholarly Articles

G.W. Bernard. “Who was Anne Boleyn?” in Anne Boleyn: Fatal Attractions. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1npjv0.7

Erin Griffey. “Introduction,” in Sartorial Politics in Early Modern Europe: Fashioning Women, edited by Erin Griffey. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2019. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/northeastern-ebooks/detail.action?docID=618461

E.W. Ives. “Faction at the Court of Henry VIII: The Fall of Anne Boleyn,” History 57, no. 190 (1972): 169-188. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24407850

Michelle L. Beer. “The Social Queen,” in Queenship at the Renaissance Courts of Britain: Catherine of Aragon and Margaret Tudor, 1503-1533, 70-96. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer, Royal Historical Society, 2018. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv1qv11t.9

Catherine L. Howey. “Dressing a Virgin Queen: Court Women, Dress, and Fashioning the Image of England's Queen Elizabeth I,” Early Modern Women 4, (Fall 2009): 201-208. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23541582

Lissa Chapman. Anne Boleyn in London. Barnsley: Pen & Sword History, 2017. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/northeastern-ebooks/reader.action?docID=4805218

Leah Kirtio. “‘The inordinate excess in apparel’: Sumptuary Legislation in Tudor England,” Constellations 3, no. 1 (2012): 17-29. https://doi.org/10.29173/cons16283

Richard Thompson Ford. Dress Codes : How the Laws of Fashion Made History. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2021. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/northeastern-ebooks/detail.action?docID=6462797

Niki Toy-Caron. “Clothing and Power in the Royal World of Catherine of Aragon, Anne Boleyn, and Elizabeth I,” University of New Hampshire Inquiry Journal, Spring 2020. https://www.unh.edu/inquiryjournal/spring-2020/clothing-and-power-royal-world-catherine-aragon-anne-boleyn-and-elizabeth-i

Downing, Sarah Jane. Fashion in the Time of William Shakespeare: 1564–1616. Bloomsbury, 2014.

Podcasts

April Calahan and Cassidy Zachary. “Tudor Fashion, an Interview with Eleri Lynn, part 1.” Dressed Podcast. December 8, 2020.

April Calahan and Cassidy Zachary. “Tudor Fashion, an Interview with Eleri Lynn, part 2.” Dressed Podcast. December 10, 2020.

Natalie Grueninger and Sarah Morris. “Anne Boleyn’s Coronation Procession with Sarah Morris.” Talking Tudors Podcast, episode 76. May 30, 2020.

Natalie Grueninger and Dr. Michelle Beer. “Katherine of Aragon & Queenship with Dr. Michelle Beer.” Talking Tudors Podcast, episode 120. July 28, 2021.

Online Sources

“Anne Boleyn.” Historic Royal Palaces. https://www.hrp.org.uk/tower-of-london/history-and-stories/anne-boleyn/#gs.fybztx

Anne Boleyn and Hever Castle.” Hever Castle & Gardens. June 7, 2021. https://www.hevercastle.co.uk/news/anne-boleyn-and-hever-castle/

Justine De Young. “1530-1539.” Fashion History Timeline. August 18, 2020. https://fashionhistory.fitnyc.edu/1530-1539/

Sarah Bochiccho. “1590-1599.” Fashion History Timeline. January 5, 2020. https://fashionhistory.fitnyc.edu/1590-1599/

Bess Chilver. “Tudor Clothes.” The Anne Boleyn Files. https://www.theanneboleynfiles.com/resources/tudor-life/tudor-clothes/

Natalie Grueninger. “Items of Dress for Queen Anne Boleyn and the Princess Elizabeth.” On the Tudor Trail. August 21, 2011. https://onthetudortrail.com/Blog/2011/08/21/items-of-dress-for-queen-anne-boleyn-the-princess-elizabeth/

Natalie Grueninger. “Anne Boleyn’s Appearance & Demeanor.” On the Tudor Trail. http://onthetudortrail.com/Blog/anne-boleyn/anne-boleyns-appearance-demeanour/

Zarrina Bull. “What did a Noble Tudor Lady wear?” On the Tudor Trail. December 9, 2013. http://onthetudortrail.com/Blog/2013/12/09/what-did-a-noble-tudor-lady-wear/

episode transcript

there are likely to be typos is here, so forgive me: it was written for audio.

Anne makes a splash

Let’s start in 1520, back when Queen Catherine of Aragon is still on the throne, regal and glorious. She’s just asked her tailor to make up three gowns in a French style as described by a man named Thomas Boleyn. He’s just come back to England from that fashion-forward country, and he’s brought his fetching daughter with him. Anne Boleyn was born in England, but she spent a lot of her formative years in France as a lady in waiting to Margaret of Austria and then Mary Tudor, Queen of France. In his memoirs, French courtier Brantome will remember Anne as ‘the fairest and most bewitching of all the lovely dames of the French court.’ So when she comes to the English court in 1521, around the age of 20, she does so with an air of fresh sophistication, blowing in like a sweet coquettish breeze.

NATALIE: I should say that Anne was also just incredibly, naturally elegant. And you probably know, you can probably think of a person now that, you know, that just looks good in everything and just knows how to put pieces together. This was Anne. This possibly, of course, came from her time in the glittering European courts that she grew up in. So people tried to emulate her and they tried to copy her didn't always work exactly. But she was known for being incredibly elegant and stylish, and knowing how to use clothing to reinforce her status as well.

What IS the court, exactly? It’s the center of government, the place where anyone with ambition wants to spend time. But it isn’t a place, exactly, but a person. Specifically, the monarch himself. The court moves with the monarch several times a year. Why?

NATALIE: When you literally have around 1,000 people living in a palace, you need to move regularly so that it can be cleaned and whatnot. But there's also, of course, the plague affected their movements a lot and during summer they always - well, I say always, most of the time up to and left London and went on what we call a royal progress. So these were magnificent progresses throughout the countryside. They're trying to get away from the plague and the sweating sickness but however they also this is also an opportunity to of course check on what your subjects are doing. And to show your magnificence into a wider range of people because normally… Of course this is, you know, it's on display a court where there's a select group of people but what you want is for regular everyday people to see you because without the support of, and we see this later in the reign without the support of the people you know your reign is in trouble.

King Henry is the sun, and his courtiers, household, and hangers on are the many stars and planets that circle him, always trying to move closer to the warmth. But the queen is her own kind of sun, with her own parallel court orbiting around her. As such, Catherine of Aragon has her own household, there to help her look and feel her queenly best.

A key part of that household is her ladies in waiting, of which Anne Boleyn has just become one. These ladies surround the queen, always, dressing and washing her, keeping her company as she sews, gossips, and prays. Some of them even sleep in the queen’s rooms on nights when King Henry doesn’t stop by. Which, these days, is happening more and more often. These ladies are often young, and single: one of the perks of being a lady in waiting is access to rich and influential men who might make advantageous husbands. But it also brings them in proximity with the king. No wonder that Henry will find so many love interests amongst them. Four of his six wives are servants of the women he’s married to. His third wife, Jane Seymour, will serve as lady in waiting to both Catherine of Aragon AND Anne Boleyn. Classy as always, Henry.

Anne is great at the game that is court life. She might not be traditionally beautiful, one contemporary puts it, but “…for behavior, manners, attire and tongue she excelled them all.” She is witty, sharp, and always captivating. Enough to catch Henry’s eye in 1524 and hold it fast. By 1526 he stops sleeping with Catherine, given up his mistress Mary – Anne Boleyn’s sister, by the way – and starts writing Anne letters that range from merely flattering to a little bit whiny. He gives her presents in the form of jewels and fine clothing: crimson satin, cloth of gold. He uses clothes to show his growing obsession with her – and with many of his wives to come. In 1540 he’ll shower his new mistress, Catherine Howard, with 23 lengths of fine soft silk.

NATALIE: So if we go back to early in Henry and Anne's relationship, he starts giving her gifts, very expensive gifts of clothing and jewelry. And this is, of course, a sign of favor. So everyone that sees her and sees her wearing something that they know Henry has given her immediately understands that there's been a shift in this relationship. And one interesting gift that he does give her of clothing are some they're called nightgowns sometimes, but they're basically a loose gown, you know, but not like the sort of dressing gowns that you and I would wear to you know, sit on the couch or watch TV. These are all incredibly beautiful fabrics fur lined, fur edged, and he gives Anne some gifts, and the tailor that's making them is Catherine of Aragon's tailor, so I just always think this poor man like, you know, he has to kind of be very careful and walk this tightrope, you know, and Henry's affections for Anne...but then of course, he's also still serving the queen.

Catherine of Aragon is a smart woman. She sees what’s going on between her husband and her maid, but there’s only so much she can do about it. Do you know what she does when Henry starts making noise about whether or not their marriage is valid? She increases her clothing budget by 50 percent. She uses fashion to try and beckon her husband back to her AND put her lady-in-waiting in her proper place. Does it work? No. But it shows us that, for a Tudor queen, clothing is a kind of weapon; we see Catherine using it to fire shot at Anne. To show her, and everyone else, that SHE is the true and rightful queen. The queen’s so-called Great Wardrobe becomes a battleground for Catherine and Anne in the years they’re forced to share Henry, stuck in a royal menage-a-trois.

fashion’s power

Let’s step back from this awkward living situation for a minute and discuss why clothes matter so much in Tudor England. We spent a lot of time in episodes 4 and 5 of our Everyday Life in Tudor England series discussing what your average Tudor women would wear, and why clothes and textiles are so prized and expensive, so go listen to those if you haven’t already. In this episode, we’re going to focus on women at the upper echelons of society, and why fashion is such a powerful tool for a queen.

So why is fashion so important to a Tudor monarch? It’s about a whole lot more than looking good.

The first thing we need to wrap our minds around is that magnificence is expected of a sovereign and his consort. When I say magnificence, I’m not just talking about looking good. The origins of the word “fashion” come from the Latin verb “to make or to shape” a person. For the Tudors, getting dressed is about not just expressing a self, but creating it. Your status, your character, your very morals are all put on display by what you wear. Tudors see magnificence as a quantifiable virtue: one on which others, like justice, depend. Magnificence is something that can be measured, and the clothes a king and queen wear is their inner virtue made tangible. Clothes, it’s thought, truly make the man – or the woman. When you’re a monarch – or, say, a rather controversial queen – that really matters.

NATALIE: So clothing was of crucial importance to queenship, to this whole display of magnificence. It reflected your status.

So, what, you’re thinking…people believe that Henry is the rightful ruler of England just because he wears nice velvet trimmed with fancy golden thread? Kinda. It’s clear that there’s a direct correlation between how magnificently a monarch dresses and how worthy they’re considered, and thereby how much support they can inspire. Take Henry VI, the guy who loses the throne during the Wars of the Roses. He was seen getting around in the same long blue gown all the time, as if he had nothing else to wear. To his subjects, that meant he didn’t have, as one of them put it, “the showing of a prince to win many hearts.” His shabby attire isn’t what cost him his crown, but it certainly didn’t help him keep it.

Meanwhile the guy who replaced him, Edward IV, aka the husband of Elizabeth Woodville,

understood the power and prestige his clothes could give. He spent some five to six million pounds a year on his wardrobe. Henry VII, the founder of the Tudor dynasty, has gone down in history as something of a penny pincher, but it turns out he spent quite lavishly on clothes. His account books show us that there was always a spike in his clothes spending during times of war and trouble: this is no coincidence. Henry VII’s claim to the throne was always a little dubious, and he knew it, so he made sure to always dress to impress. This isn’t just to inspire love from his subjects. Ambassadors are always writing home to their home countries in painstaking detail about the state of the English royal household, from the privy attendant to the queen. How fancy are the materials of their dresses? How well are they kept and maintained? These things offer a clear window into how well the English monarchy is doing.

Of course, it isn’t just a king people are looking at closely. His image is only as solid as that of the queen by his side. Catherine of Aragon understands the power of her wardrobe, both to underscore Henry’s rule AND shore up her own power. Anne Boleyn might be more famous than her predecessor when it comes to fashion, but there’s no denying that Catherine knew how to dress for what she wanted. When she first arrived in England, she paraded through London dressed in splendid Spanish fashion, showcasing her powerful relations back home. But it wasn’t long before she started wearing English styles, using them as a way of connecting and endearing herself to the people. Over her long reign, she wore Spanish or English dress depending on which one suited the political and social situation. Anne, by contrast, will continue to wear mostly French fashion: trendy, for sure, but it doesn’t exactly make her seem like a woman of the people.

GETTING DRESSED with a queen

Let’s get back to Anne, who has been hanging out in her underwear since this episode’s intro, and help her decide what to wear. Wait, actually, first let’s wander a few palatial rooms over and see what Henry’s putting on. I know, I know: do we really need to see Henry VIII in his altogether? No thank you! But it’s important we see what it is he’s wearing, as he sets the tone for English fashion, but also because it tells us a lot about the Tudor court at this period, and about the women who help rule it.

Unlike his rather austere father, Henry VIII is all about ostentation: the bolder and brighter the outfit, the better. But this isn’t just a matter of personal preference. He creates the image he wants to project with the silhouettes he chooses to wear. Mostly he wants to underscore his youth and his exuberance: this ain’t my daddy’s court, ya’ll! And so he spends quite lavishly on his ensembles. His layers are simple enough: he’ll wear a linen shirt as a base layer, very fine, of course, and often embroidered at the cuffs and collar. Henry has seamstresses to mend this layer when needed, but it’s considered a wifely duty to make shirts, even at this level of society. Which is how Henry’s shirts become something that Catherine and Anne go to battle over. In 1530, when Anne discovers a servant bringing Henry’s old shirts to Catherine’s chambers so she can mend them, she freaks. Darning the king’s underwear is an intimate, wifely duty, and would legitimize Catherine’s queenship in the eyes of the entire court. So Anne nips the whole thing in the bud, making sure that SHE will be the one darning Henry’s undies ever after. Well, she hires another woman to do it, obviously, but it’s the look of the thing!

Next up, Henry adds a doublet, which is a kind of long-sleeved jacket top. An inventory from 1516 says that Henry owned 134 of these things, in 29 different colors. He makes it racy by lowering the neckline of the doublet, letting his linen show over the top. He also popularizes something called ‘slashing’, which the queen will also take on board. Here’s a visual: grab your nicest sweater vest. Now take a razor and cut, or slash, little rips in it, through which you can see whatever you’re wearing underneath. This is essentially what slashing is. And it’s fashionable because it shows not just your top, but your bottom layer: you’re rich enough to afford to cut holes in your shirt? Well then.

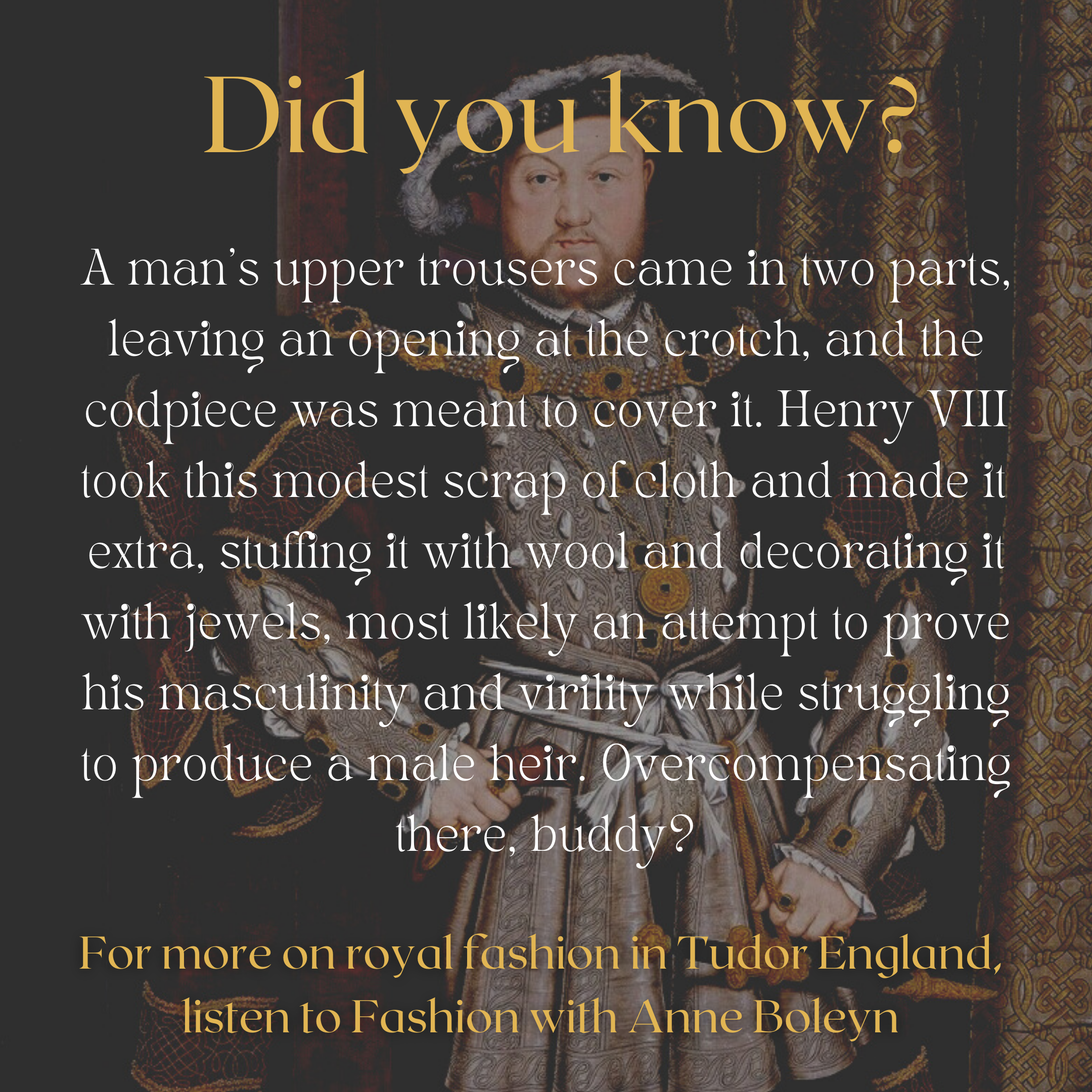

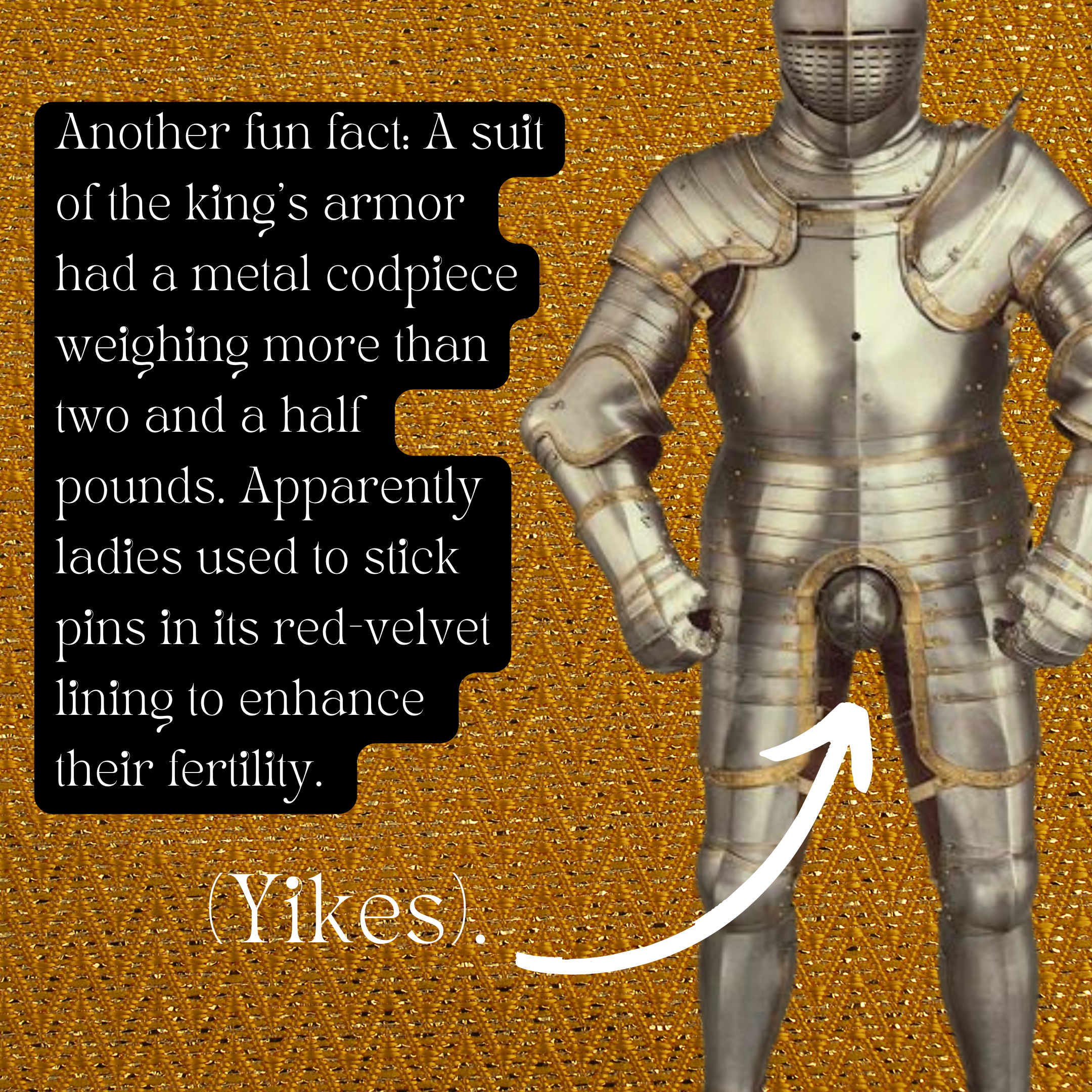

Down below, Henry will slip on some nether hose, which encase his calves in fine wool, linen or silk. His upper hose are essentially a fancy form of baggy shorts that are tied to the doublet to create a kind of suit situation. But can we talk about the giant codpiece – I mean elephant – in the room? What is the DEAL with this giant cloth phallus? Remember that a gent’s clothes in this age are made of several parts that are tied or pinned together; the legs of the upper hose separate pieces, leaving a gaping crack running between them that certainly makes it easier to pee. But to avoid public flashing, they needed something to cover it up, hence the codpiece. It started as a flap of fabric, but Henry takes the codpiece to a WHOLE new level. In his court, we start seeing them embellished with jewels and decorations: bedazzled crotches. Alrighty. They’re padded, too, stuffed with cork and wool, swelling to occasionally ridiculous proportions. Watch out, Henry: your tiny man complex is showing! The codpiece becomes a walking, not-quite-talking symbol of Henry’s virility. It’s a way of pumping up his manhood, but it’s also a clear sign of anxiety about how much trouble he’s having making heirs.

Henry might put on a jerkin, which is essentially a vest, then a gown, which Henry likes to have hemmed to just above the knee so we can all appreciate his finely toned calves. On top of all that comes a coat. That’s a lot of layers! No wonder a square, boxy frame is so popular in Henry’s court. That’s especially true as he starts getting older and…well…much, much larger. By popularizing a boxy frame, he glamorizes his increasing size, aligning it with his magnificence. He wants to take up space because it makes him look imposing. Something his daughter, Elizabeth I, will take on board during her own reign. More on that later.

As queen, Anne is both a model and a mirror, for everyone at court and any who aspire to live at the heart of it. Every day of her reign, she makes some fashionable change. Back in episode 5, we got dressed as a Tudor woman, putting on a smock, a petticoat, a kirtle, and a gown. If you haven’t listened, I suggest you do, as we walk through each of these layers in detail. But right now we’re dressing a queen, which is complicated and time-consuming. First, her ladies will warm her smock – aka her undies – by the fire. This shift dress is made of linen – in Anne’s case, probably a very fine linen, likely Holland cloth, trimmed with white lace, and embroidered. She’ll slip on a soft pair of fine wool stockings or hose, held in place by garters made from ribbon, and sometimes a pair of silk ones over that. Then comes her petticoat, made of fine wool, which is meant to act as a barrier and insulator between her body and the finest layers of her outfit. The term “petticoat” comes from the French for “little coat,” and both men and women wear them. Most of them are made of fancy red fabric, as red is the color thought to protect and herald good health. Then on goes her kirtle, the sleeveless body whose stiffness is meant to lift those bubbies and smooth everything out. We’ll also be working with a farthingale. Katherine of Aragon brought this fashion over from Spain, which influenced all the women at court. The word farthingale comes from the Spanish word verdugos, used to describe smooth twigs, which is what was typically used to craft this structured underskirt. Willow twigs were pushed through teeny sleeves in one’s petticoat, forming hoops that give it structure and form a kind of bell around our bottom halves. They’re pretty narrow in Anne’s day, unlike the farthingales that we’ll see her daughter Elizabeth I bring into fashion.

The forepart is next, an apron-like panel of fabric that hangs down the front. It’s often lavishly decorated, made out of sumptuous fabrics. It’s a bit of an optical illusion, the forepart: it can easily be mistaken for a petticoat. Imagine: the queen is SO prosperous that she can afford to have an entire skirt made of that sumptuous brocade! After that we will slip on an overgown with long ‘hanging sleeves’. Then come the lower sleeves, which often match the forepart, and are detachable. Anne will also wear a placard: a lovingly decorated fake bodice that gets pinned to her chest to hide her dresses’ laces. Sometimes they get pinned under the laces, which is nice for pregnant Tudor ladies, as it both hides their growing belly and gives it room to move. Even so, the placard is not what you’d consider a comfortable piece of clothing. It’s more like chest armor, rigidly squashing your top half into shape. And no matter what the HBO show the Tudors might suggest, you’d best not show too much cleavage here. That iconic square neckline that hint at the treasures that lie below it, but only Henry is meant to see the laces that will set them free.

When it comes to fabric, Queen Anne is going to be rocking things very few women in England can afford to. In our era, the most expensive clothes that money can buy are made so because of the designer who created them. It’s about the prestige of the name. But in Tudor England, a big part of their value comes from the textiles themselves.

NATALIE: So in all the accounts we have not only a variety of materials, just incredibly lavish materials mostly being imported from Europe. So Henry basically had first dibs, so when the merchants would come into London with all their new wares, Henry got to see it all first because of course he has have the best of everything. And I imagine Anne also saw everything and selected.

Much of what a queen is wearing doesn’t come from English farms, but abroad, from Holland and France and Venice. Even color has a monetary value. The more expensive a color is to produce with the natural dyes of the era, the most coveted it is.

Take scarlet, which is a name for a fine type of cloth AND a sought-after color. The brightest red dye used to make it is called carmine. It’s made with cochineal: insects dried, crushed, and brought by ship over from South and Central America. Some red food coloring is still made this way today. True black, too, is expensive to make, so if you see someone wearing it you can make certain assumptions about her status. Catherine of Aragon favors black and purple silk and velvet, creating a look that is both regal AND pious. And then there’s cloth of gold and silver: a luxury staple for kings and queens. To make it, goldbeaters hammer metal into thin sheets, then cut into very fine strips. Those strips are wrapped tightly around silk thread, or carefully woven into textiles on its own. Sometimes someone will weave these gold strips in with a brightly colored contrasting silk, which is where we get such luxuries as “crimson cloth of gold.”

The Field of the Cloth of Gold, oil painting of circa 1545 in the Royal Collection at Hampton Court. Henry VIII on horseback approaches at bottom left. You can tell it’s him because of all that cloth of gold.

NATALIE: …it was certainly eye catching, and if you imagine the…you know that some of the clothing of course had had actual real gold thread and silver thread, and imagine that with candlelight and how incredible that must have looked it's, yeah, it's quite amazing.

Of course, all of this fine cloth cost a goodly fortune. An inventory of Henry VIII’s wardrobe from 1547 says that just one yard of cloth of gold is worth 53 shillings, 8 pence, which is equivalent to 88 days’ work for a skilled laborer. Another yard of fabric from his collection, black with silver, would be worth some 3,000 pounds today.

NATALIE: Henry apparently spent around 4,000 pounds per year - this is pounds in Tudor money, it's not pounds now, which I think is something like 1.5 million pounds today or something ridiculous like that. He spent that much money on his clothing per year. So this demonstrates just how important it was to look the part, to look magnificent. You have to dazzle everyone around you...

But when textiles cost this much, sometimes even queens have to pinch pennies. That’s why it’s handy that our outfits are essentially stitched together piece by piece. For the savvy queen who wants to look like she’s never in the same outfit twice, she can mix and match her sleeves and forepart with a new gown. Elizabeth I will be particularly ace at this. Her wardrobe is famously huge, including some 6,000 dresses, but really it is more like 2,000. Elizabeth didn’t have as much money as her dad, as he spent so much of it, and so she will get really good at making her wardrobe look expansive when it really isn’t. She cleverly mixes and matches her pieces, and she has her tailors alter them constantly, remaking them to look like new. In one six-month period, her tailor William Jones altered 40 gowns. She will also make it known that she loves gifts of textiles and jewels above all things, so she will be gifted lots of things she can turn into fresh outfits.

feeling sumptuous

Most of the women in England could never afford the kinds of outfits Anne or Catherine are wearing. Even if they could, they couldn’t legally wear them. Not with the sumptuary laws that dictate who can wear what.

These laws, which have been around in some form since medieval times, are all about codifying what people wear. Not just the cut of your jacket, mind, but what material it’s made from and what color the cloth might be. Henry’s sumptuary laws are broken up by rank and/or income, which means you can tell where someone fits in the grand social scheme of things with one quick glance at their clothes. Cloth of silver or gold is ONLY for royals. Same with purple silk. Velvet of blue or red is only yours for the taking if you’re the rank of knight or above. Servants, meanwhile, can’t wear gowns with more than 2.7 meters of fabric in them, and farm workers are forbidden to wear cloth that’s worth more than 2 shillings per yard.

Is anyone going around actually policing these very strict rules? Not really. These rules are easy enough to flout, and the people who break them most often are nobility.

These laws have a practical purpose. Because the vast majority of our finest fabrics come from Europe, these laws protect the English wool and linen industry. But also, they are about drawing very clear lines between the classes. A rich merchant can’t wear the same doublet as King Henry. Because…well…that would be confusing! Henry in particular wants his court to look fly, a fetching backdrop, but NEVER more magnificent than him. Interestingly, most of these don’t apply to women in Henry VIII’s era. They can wear whatever they like.

Sort of. For women at court, clothing is status. You want to demonstrate a sense of current fashion – to draw a visual link between yourself and the queen. But your clothing also needs to speak to your modesty. As Hannah Wooleys will write in 1673, in The Gentlewoman’s Companion; or, a Guide to the Female Sex, women should: “incline somewhat to the Mode of Court (which is the source and foundation of fashion); but let the example of the most sober, moderate, and modest be the pattern of your imitation.” You wouldn’t want someone to think you weren’t a proper lady, would you? As in so many times and places, a Tudor woman has to think hard about what her clothes say about her virtue. Even a queen – perhaps especially her. There’s a REASON Catherine of Aragon wore white when she married Henry: it was meant as a symbol of her virginity, which had so recently been contested. As is true throughout the ages, a famous woman’s outfits are constantly at risk of calling her character, and her virtue, into question.

it’s all about that hood

Once Anne is dressed, her hair will be brushed and mostly covered. ALL ladies in Tudor England are wearing head coverings: A white linen cap and then some kind of hood. People will think you’re a hussy otherwise. But what KIND of hood? This is a loaded question. One choice is the English, or Gable, hood. This is kind of like a hat in the shape of an open pentagon that will cover all of our hair, with lapets that hang down over the ears, a bit nunlike. And then there’s the French hood. It comes from – you guessed it – France, and it becomes quite popular during Anne’s reign. Women like Henry’s sister, Margaret, and Catherine of Aragon both wore the French hood before she did, but Anne’s often credited with making it a Thing. It’s rounded instead of boxy, fitting close to the head, and it's considered just a little bit racy because of how it sits back a little, showing a sliver of hair at the front. But the style, imported from outside of England, picks up certain connotations. It becomes associated with Anne, her supporters, and everything she comes to represent. That includes Protestantism – Anne is a real devotee - and support for the Church of England. A woman’s hood suddenly becomes dangerously political. That’s why our next queen, Jane Seymour will ban the French hood, deeming the English one a much more patriotic and, truth be told, safer choice.

Let’s not forget our jewellery. Anne will definitely be wearing some, and not just that sexy choker you’re imaging with that big, fancy looking B. She’ll be rocking pearls and jewels in gold settings, worn as pendants or brooches, on necklines, sleeves, and hoods. These, too, carry a potent kind of power. When Henry starts courting her, jewels are one of the first gifts he gives her. In 1532, Spanish ambassador and Anne Hater Eustace Chapuys reports that “the Lady has been busy in buying costly dresses, and the King, not content with having given her his jewels, sent the duke of Norfolk to obtain the queen’s as well.” Henry wants Anne to have the royal jewels to underscore her position and destabilize Catherine’s, and Catherine is livid about it. She refuses, as she puts it, “to adorn a person who is the scandal of Christendom.” But she can’t fight Henry’s iron will, and eventually has to give them over. How does it make Anne feel, to wrap her neck in jewels that another beloved queen wore not long ago? It’s hard to say. But the queen’s jewelry and wardrobe aren’t her own: they belong to her position. Which should mean she gets to keep them for her lifetime, but it turns out the position of England’s queen isn’t as stable as a lady might like.

But the queen doesn’t only have her own wardrobe to think about. She’s also responsible for outfitting the entirety of her household: ladies in waiting and servants too. There’s what’s called the dynastic livery, ordered in bulk twice a year for pages, minstrels, stable staff, basically anyone who works for the monarchs. Both king and queen have something called the Domus Magnificence: the Guard Chamber who keep her safe, the Privy Chamber who deal with all of her most intimate actions. These are the people who surround the Queen, always, and they all require special uniforms. Members of the queen’s household wear her colors and her badge.

NATALIE: …because of course everyone in your household has to look good. There can't be any one kind of walking around not looking great because they are a reflection of your magnificence as well. So where Anne is reflecting Henry's court, her household is reflecting her magnificence, so it's a matter of really just dazzling everyone.

Then there is the livery given to individuals, which will vary depending on their relationship with the queen. They are an extension of her own image, reflecting her magnificence and honor, and through them she can make subtle statements to anyone who’s paying attention.

NATALIE: Of course, livery which is clothing that was given to your household is incredibly important because this extends the Queen's presence at court. So even if Anne was not able to, to....obviously she can't be everywhere at the same time. Her household members are in her livery and everyone knows they're probably wearing her badge or her colors. And people know that's the Queen's people. And it was so important, in fact, that lady Lyle which was living in Calais during the Anne's reign was absolutely, you know, I don't know how many letters she wrote four or five that survive, absolutely begging to be given this livery. She wanted to wear it in Calais, because it shows a sense of belonging. You are part of the Queen's household.

Thus the queen’s livery becomes a battleground for Catherine and Anne. When Anne’s first married to Henry, Catherine boldly orders new livery for her household, embroidered with intertwined H’s and K’s. Anne hits back by having a special monogram sewn into HER household’s livery. It reads: “this is how it is going to be, however much people grumble.”

dress language

When Anne and Catherine of Aragon get dressed, everything about their outfits is important. They are both forever on display, always observed. As a controversial public figure, Anne is constantly walking a high wire: one wrong move, sartorial or otherwise, can mean the difference between her rise and fall. But fashion also gives her a unique kind of voice. A good Tudor woman may not be able to openly express political opinions, but her wardrobe gives her agency, operating as a form of silent, powerful speech.

NATALIE: So clothing reflects different allegiances. So for example, you know if Anne's wanting to emphasize her, her French links, she might of course appear in a French hood, or that kind of thing. We know Catherine of Aragon, sometimes when she wanted to really emphasize her Spanish heritage would wear a more Spanish style, gown or outfit. So they reflect those allegiances like that as well.

In 1520, at an important meeting between Henry VIII and Charles V, she complemented Henry by wearing cloth of gold and pearls, but her distinctly Spanish style also flattered Charles. At other times, she used fashion to subtly rebuke Henry. That same year, at the famous meeting between the French and English kings called the Field of Cloth of Gold, Catherine pointedly wore a Spanish headdress: a visual sign of her displeasure. That’s some soft power at work right there.

Anne, of course, takes pains to dress quite differently than Catherine, continuing to wear distinctly French styles. Given England’s oft-tense relationship with that country, this does not win her a lot of devotees during her reign.

Henry weds Anne in a secret ceremony in 1533. They try to keep it under wraps, but her sudden change in clothing is part of what gives the game away. As one source notes, “On Saturday…dame Anne went to mass in Royal state, loaded with jewels, clothed in a robe of cloth of gold frieze…and was brought to church, and brought back with the solemnities or even more, which were used to the queen.” For her coronation she wears French styles, as do her ladies. But on her coronation medal, issued a year later, she is pictured in an English gable hood and English-style clothes.

NATALIE: …in 1534, the only surviving contemporary likeness of Anne Boleyn is a portrait metal, it's tiny, it's like the size of a coin. And she's seen dressed in an English what we would call an English Gable hood. So not her typical, you know, French hood that she was associated with. And it does appear that she's wearing pieces that were in fact part of the Queen's wardrobe. So these are pieces that pass on to the other queens and that she probably got from Catherine of Aragon. So she's making a very clear statement there that she is Henry's legitimate wife and that she's English.

It’s a gesture meant to make her look patriotic, as her image already needs a serious facelift. MANY people don’t like her or see her as the rightful queen.

And just to add to the scandal, Anne’s already pregnant. On September 7, 1533, she gives birth to a daughter: Elizabeth. It’s not the outcome she or Henry were praying for: the baby’s not a boy, after all. But with Elizabeth’s birth, Anne feels confident enough to flex her queenly muscles. And she does it, once again, through clothes. She demands that Catherine of Aragon send her the christening gown that Mary, Henry’s eldest daughter, wore. Catherine, it will not surprise you to hear, is having none of it. She writes, “God forbid that I should ever be so badly advised as to give help, assistance, or favor, directly or indirectly in a case so horrible as this.” Things get so heated that Henry has to intervene, showing us how intensely symbolic even a child’s gown can be.

Anne badly needs to have a son to cement her queenship, but there’s no doubt she loves her baby daughter. Sadly, she won’t get to see her grow up to become one of England’s most famous monarchs. Let’s give her the gift of time travel, just this one time, so we can see how her daughter will change English fashion and take royal power dressing to a WHOLE other level.

LONG LIVE THE QUEEN

When Elizabeth takes the throne, she already knows all too well about dressing for the job you want. From Day One of her reign, she’s magnificently dressed. When she entered rooms she literally sparkles, as one courtier writes, “like starlight, thick with jewels.”

But Elizabeth’s fashion is about SO much more than shining bright. She is the sovereign, and thus she sets the fashions, and fashion is powerful. She very consciously uses it to shape her image as the rightful monarch and silence haters who think that women aren’t supposed to rule.

First, we see the silhouettes, which really haven’t altered all THAT much since the beginning of the dynasty, change quite a lot for both men AND women. Fashion for women becomes much more expansive. Hair gets bigger, skirts expand, and ruffs…oh my, the ruffs. While the farthingale that Anne Boleyn is wearing is cone shaped, made with reeds or rope, Elizabeth’s reign sees them slowly but surely wider. Eventually, Elizabeth has to have a wheel fashioned for her farthingale, made possible by the increasing availability of whalebone due to expeditions across the Atlantic Ocean. Imagine that an innertube and the rings of Saturn had a love child: this is what a drum farthingale looks like, but it goes around your waist, sitting over a padded bum roll to take some of its weight. The so-called drum farthingale makes one’s skirts take on the size and approximate shape of a very giant bread box. Elizabeth could host an entire tea party on top of her dress, should she like to. This is also when we start to see the introduction of the body. No, not our physical bodies: this thing is as close to a bra as we’re likely to get in this age. I want you to picture a corset. Now picture one with lots of whalebone sewn into it to make it nice and stiff, with a kind of shelf jutting out of the bottom: these are our bodies. They’re often called ‘a pair of bodies’ because they come in two pieces, which are laced together to smooth us down and cage us in.

Look, these changes might not be a very practical, but it sure does allow us ladies to take up a whole lot of space. If you see the queen coming, you’d better MOVE, son.

Speaking of taking up space, let’s talk about ruffs. These starched lace collars stick out from around the queen’s neck, making her look a bit like a magnificently frilly lizard. Cuffs and ruffs have been around since Anne’s time, used as a subtly frilly collar, but Elizabeth really makes them into an independent clothing item. Ruff innovation is once again made possible by whalebone - bad for whales, but great for fashion. – and the increased use of starch. Starch is derived from grains, which was a little controversial, especially during times of famine, but that doesn’t stop Elizabeth’s court from getting into it. Ruffs are made of fine linen and lace, which is then dipped in starch paste over and over and left to dry, making it stand at rigid attention. Many can only be worn once before they start wilting from weather or body heat. Elizabeth has her own dedicated starcher, and it’s a full-time job. At one point, ruffs grow so huge that they need wires to support them. The biggest of the accordion-style ruffs could incorporate some 40 yards of linen in their many-pleated folds. Some people see them as the height of gaudy excess. Some complained, like Philip Stubbs in 1583: “they have great and monstrous ruffs, made either of cambric, holland, lawn, whereof some be a quarter of a yard deep.”

Pure magnificence. I mean…where to start? The drum farthingale, the painted pond full of flowers and animals, the lavish ruff and pearls. Elizabeth I knew how to make a statement. Even her shoes are full of bling.

Elizabeth I of England, 1592, from Hardwick Hall. [Wikicommons].

Paintings make all starched ruffs looks white, and some are, but others are tinted by different dyes in the starch. Yellow, green, pink: a ruff can be a surprisingly colorful accessory. Blue ruffs become popular, too. One of the reasons, writes Thomas Platter, is “because the womenfolk of England who have mostly blue-grey eyes, and are fair and pretty…lay great store by ruffs and starch them blue so that their complexion shall appear whiter.” But you’d better not be caught wearing one in the 1590s. Elizabeth bans blue ruffs, as it’s the color of Scotland’s flag. But others suggest that Elizabeth bans the color because, blue ruffs have become quite a fashion amongst London’s prostitutes.

These rigid fashions change the way women at court use their bodies, making their movements slower and more deliberate, and forcing them to hold their arms in front and their head high. But these expansive lines and rigid set of the Queen’s outfits also underscores a woman’s power and her presence. Much like the shoulder padded power suits of the 1980s, this is Elizabeth showing that SHE is the dominant figure here, not any man. By contrast, male fashions become smaller and more modest. Gone are those square, bulky shoulders, the codpiece finally makes its exit, and the upper hose start slimming down and creeping up to reveal a LOT more leg. Men’s attire becomes, in essence, much skimpier, putting the men on display for their queen. Bow down, boys.

But Elizabeth doesn’t only emasculate her many admirers. She also starts taking on elements of men’s fashion and making them her own. Doublets for women start showing up around the mid-1570s, and buttons – usually men only – are ordered for the queen in bulk. Is this the influence of European fashion, or is Elizabeth using fashion to visibly link herself with kingship? And she will say in a fashion speech, she might have the body of a woman, but she has the heart of a king. Why not wear a fetching doublet to express that?

You may also notice that, in her portraits, Elizabeth is pretty much never wearing a hood. Why isn’t this considered the era’s biggest scandal? Because as a virgin queen without a husband, she isn’t entitled to wear it for modesty. Her hair is a symbol of her continued purity, which is an important part of her image. Gradually it becomes the style for all women at court, making room for innovation in hair styling.

Under Henry VIII, women were exempt from sumptuary laws. After all, Henry didn’t see them as a threat to his magnificence. They were accessories, not power players. But now that a woman is indeed ruling the country, suddenly a woman in a very fine dress presents a threat. Elizabeth needs to be the most finely dressed, always – she does not tolerate anyone trying to outshine her. Especially as in her court, clothes send messages like never before.

Elizabeth’s court, and her clothes, are rich with symbolism. She is very thoughtful about what colors she wears. In Tudor England, colors have meaning. Red is linked to health and power, green with youth and hope. Elizabeth’s signature colors are white, which represents purity, and black, which represents constancy. She also takes to wearing quite a lot of pearls, another symbol of virginity. It’s all a means by which to create her image; the mythologize her as the Virgin Queen. That image allows her to rule on her own, without a man beside her. I mean, she’s basically married to England! This mythmaking is a big part of what helps her stay in power.

But Elizabeth takes sartorial symbolism ever further. She loves games, puzzles, and codes. A book comes out in 1586 called A Choice of Emblems, which is a symbols dictionary. It became a language through which her subjects could praise and celebrate their queen. She’s given presents that feature snakes, a symbol of wisdom, and rainbows to represent the celestial. If you look at her Rainbow Portrait, which I’ll put in the show notes, you’ll see her holding a rainbow – linking her to the heavens – dripping in pearls, and dressed in a gown covered in eyes and ears. Many people have assumed this was the painter’s invention, but some historians think the gown is actually hand painted. It’s as if she is saying to whoever sees the portrait, “I hear and see all, so don’t test me.” And I’ll bet her courtiers take heed.

The other form of decoration we see on lavish display in that portrait is naturalistic embroidery, which becomes super fashionable when Elizabeth comes onto the scene. Elizabethan dresses, vests, and gloves show the natural world in incredibly accurate detail, from spiders and birds to flowers and strawberries. These prints are coming from new books on botanicals: for the first time, we’re seeing books printed not just about religion, but domestic things too, including fashion. It becomes a mark of scholarship to recreate them on fabric – a way of categorizing and mastering nature. But these symbols have meaning, too: pansies represent thought, while rosemary means remembrance. And then of course there’s the Tudor rose, the sigil of the queen herself. Professional embroidery is mostly undertaken by men, but for aristocratic women it is a noble occupation: one that they could use to share opinions, make gifts, and express themselves creatively and intellectually. It’s even a way of making connections with their queen. Highborn women often embroider clothes specifically for Elizabeth, and she can express her favor – or her displeasure – by whether she decides to wear them.

ANNE’s END

Let’s get back in Anne in 1533. She’s had her baby girl, and there’s plenty of time to have the male child Henry needs to assure his dynasty. Half of England might dislike her, but Anne has every reason to look forward to all the years of queenship to come. In 1536, she and Henry feel so sure of their future that they make a pretty tactless sartorial choice. When Catherine of Aragon dies, Anne and Henry wear YELLOW to court, which signifies hope and sunshine. But that sunshine turns to clouds soon enough. On the day of Catherine’s funeral, Anne miscarries a child. A personal horror, of course, but it’s also a political disaster. Is that why Henry starts to turn cold on her? Perhaps, but it certainly isn’t the only reason. Some say she’s committed adultery, or at the very least flirting too loudly. Some say the king is sick of having such a loud and headstrong wife. He’s most certainly already fallen in love with another woman. All we can be sure of is that Anne Boleyn’s fall is a complicated thing, and no commanding outfit has the power to save her from it. She soon finds herself in serious trouble. Anne and five men, one of whom is her brother, are accused of several crimes, including adultery, conspiracy, and never having truly loved the king. One of the charges that doesn’t get talked about quite so often is that she and her brother laughed at the king’s clothes.

Anne is taken to the Tower of London. Catherine Howard, Henry’s fourth wife, will suffer a similar humiliation years from now, stripped of all her fine clothes and jewels. Her jailors strip away all signs of her queenly status, a punishment and a statement to any who see her. It’s likely Anne goes through the same.

No one could have predicted how swift Anne’s fall would be, including the lady herself. She suffers blow after blow, at the end. Her brother is beheaded; her marriage to Henry is deemed illegitimate, and her daughter is no longer an heir to the throne. On May 19, when Anne is led to the scaffold, she has very little power or agency left to her. But still, she uses fashion to project the vision she wants the people to see. She arrives at the scaffold in dark colors, an ermine cloak, and – interestingly – an English Gable hood. She goes to her death looking as regal as she can.

The day after Anne’s execution, Henry is engaged to her lady in waiting, Jane Seymour. And while she may go out of her way to wear a different kind of hood than Anne did, she will inherit most of Anne’s clothes. The queen’s great wardrobe will be passed down to all of Henry’s wives over the years, sartorial ghosts of the women who came before her. Fine fabrics that echo with the influence she once wielded, even only briefly. Her armor, even if it couldn’t keep her safe.

music

All music, which comes from in and around the Tudor era, comes to us courtesy of John Sayles.

voiceovers

Eva Folch, Jordan, and Baz at Voiceover Elite.