Clara Barton: Angel of the Battlefield

Season 1, episode 3

If you know anything about Civil War nursing, then you'll have heard of Clara Barton.

She was many things: A celebrated teacher, a pioneering woman civil servant, a battlefield nurse, a public speaker, and a leader of many initiatives, whether the men around her were keen on them or not. In a time when single, middle-class women didn't have all that many career options, she went ahead and had, oh, let's call it five different careers. This dynamo contained many contradictions: she was incredibly shy, but also brazen in her pursuit of her goals; she was anxious and insecure, but also sure and steady. This "Angel of the Battlefield" was a whole lot more dynamic, and a whole lot more complicated, than you might think. Let's re-examine the life of this fascinating character.

Grab a few bedsheets, your first aid kit, and a traveling camp bed. Let's go traveling.

“When I reached [home], and looked in the mirror, my face was still the color of gunpowder, a deep blue. Oh yes, I went to the front!

”

My Sources

(My Faves are in bold)

podcasts

The History Chicks, Episode 14. I adore these ladies, always, and they did a great job of painting a picture of Clara's life. If you haven't listened to them yet, go do it. They are my go-to, feel good, enjoy women's history dynamos.

Books

Stories from My Childhood by Clara Barton. You can find it on Archive.org.

A Quiet Will: The Life of Clara Barton by William E. Barton. Ebook published by Big Byte Books, June 2015.

Clara Barton: Professional Angel by Elizabeth Brown Pryor, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1988. This was my favorite, as I felt it gave the least biased view of Clara, and delved the deepest into the realities of what she had to face.

online

The Clara Barton Missing Soldiers Office Museum. This is an incredible resource. Not only do they have a heap of great information on Clara Barton's life and work, but on nursing in general and the many other women who contributed in her lifetime. You'll find great primary resources, and so many cool stories. Plus, you can visit her Missing Soldiers Office! Next time I'm home in D.C., I'll be stopping in for sure.

The Clara Barton Papers. I heart the Library of Congress; they have digitized a HUGE amount of her correspondence, diary entries, speech drafts, and other pieces of writing.

The National Park Service and the Clara Barton Museum. This one has a lot of great images from Clara's life, including some of the everyday stuff she had around her.

"Clara Barton: Angel of the Battlefield." by Claudia Swain. Boundary Stones: WETA's Local History blog, August 2016.

"The Shape of Your Head and the Shape of Your Mind." Erika Janik, The Atlantic, January 2014.

"Clara Barton." The National Park Service.

"Founder Clara Barton." The American Red Cross.

For the sources I used on nursing more generally during the Civil War, check out my post on Lady Nurses (episode 2).

Clara rockin' that bustle look in her later years. This is thought to have been take in Danville, NY, around age 60, and right around the time she was founding the American Red Cross. Go ahead, girl: you've got a lot to smirk about!

Courtesy of the Clara Barton National Historic Site/National Park Service.

episode transcript

Keep in mind that this is a draft document, and it won't match the episode exactly. i add and delete as i go, ad-libbing all sorts of absurdities in the dark confines of my recording fort.

Clarissa Harlowe Barton was born in Oxford, Massachusetts, on Christmas Day, 1821. She was the fifth and last child of the family, and the youngest of the bunch by about a decade. So while Clara, who they often called Baby, grew up surrounded by loving siblings, they often felt more like parents, and she felt like an only child. But being Baby came with advantages: she was everybody’s pet project. Each family member took it upon themselves to educate her, often in things that would come in handy later in life.

Her dad, Stephen Barton, had married young Sara Stone back in 1804. Rather hastily, I might add, as their first child was born only five months later. Whoops! The Bartons and Stones had long been a part of this rural New England community: full of churches, clapboard houses, farms and mills. Now a well-respected middle-class farmer, Stephen was considered a man of sound judgement and stately bearing. But as a young man, he joined up with the military, going off to fight in the so-called Indian War out on the Ohio frontier. His three years of service left a lasting impression on Stephen, full of stories he liked to tell Clara about around the fire. “I listened breathlessly to his war stories,” she said. “Illustrations were called for and we made battles and fought them.” Clara absolutely adored her dad. They used to set up mock battles and talked about politics--not the most mainstream of occupations for a girl of the time.

But each member of the family were her teachers, in one way or another, and Clara was quick and eager to learn. She said she didn’t remember a time when she wasn’t able to read. Her older sisters taught her writing, art, literature and geography. Her brother Stephen disliked school so much as a young buck that, at 12, he still couldn’t read. But this late-bloomer went on to teach himself math, which he became ace at. So when he wasn’t busy working at his mill, that’s what he taught her. Stephen and her other brother David, dashing adventurer and all-around wild child, also taught her other unseemly things for a lady. For example, they taught her how to throw a ball “like a boy”, to hammer a nail into a board, and tie good knots. David was also a very dedicated lover of horses. So when Clara was five, he took her out into the fields with some young colts and popped her up on one - no saddle, that’s fine - and they rode off at top speed into the sunset. Yikes. Clara would become an amazing horsewoman who would often awe and shock those around her by riding astride instead of sidesaddle! Oh my.

Her busy and industrious mother taught her the domestic arts every woman had to learn: cleaning, sewing, cooking, etc., though she wasn’t ever so great at making clothes. This sounds less glamorous than bareback horse riding, but these skills were some of the ones she was most grateful for later. She credited her mom with the fact that, even out on a battlefield, she could bake a perfect pie with crinkly edges.

But this rosy portrait doesn’t tell the whole story. Where her dad was calm, her mom was full of nervous energy, and a weird habit of letting vegetables and pies go half bad before she’d let anyone eat them. Right. She was tough to impress, and quick to anger. Once she pulled apart a new cook stove and threw it into the pond because she didn’t like the way it heated. So this house was not without its parental fights and rages. And then there was her eldest sister, Dolly, intense and smart and very troubled. When Clara was six, she suffered some kind of mental breakdown. She’d fly into wild rages: once, she almost killed someone with an ax. So there was that.

Her family was full of big, driven, intense, and erratic personalities. Picture yourself at a raucous family dinner, surrounded by loud voices fighting over that basket of bread rolls. You have two choices: rise to meet the madness, or shrink back against the wall. Young Clara took the second option. She grew incredibly shy, retreating ever further inward, extremely sensitive to any critique or joke. She wanted attention and praise from her family - desperately. She wanted to be able to hold her own. But she felt outmatched by her much older siblings. And as the youngest, she got teased her a lot, which seemed to give her a debilitating fear of being wrong. Take this comment, which she wrote about her childhood:

“In the earlier years of my life, I remember nothing but fear.”

She also lived in fear of being a burden. The fact that her mom sometimes seemed to find her one didn’t help. She found it overwhelming to ask for anything. Her mother was mystified by how, instead of just saying she needed a new dress, she’d burst into tears and run to her room. Understanding of a sensitive nature, her mother wasn’t.

Plus, like many children in large households, Clara often felt lost in the shuffle. In this family of busy, ambitious people, she’d either get intense attention - critical and pointed, making her a canvas to paint their own ambitions on - or none at all. So Clara grew up with an intense desire for both attention and approval. She’d soon find it through being a super good student.

At four, she was sent to school. This was not the preschools of the 21st century, with naps and snacktime and finger paints. Countries schools usually featured one school room, one teacher, and some 40 students of all different ages. She was by far the youngest kid there, and shockingly timid. But that didn’t mean she wasn’t super keen to do well. After dutifully spelling out words like dog and cat, she got bored, looked down at her speller at the most advanced section, and told her teacher, ‘I read an artichoke’. To say she was an accelerated learner is putting it mildly.

And wouldn’t you know it, doing well at school won her the praise she was looking for, so she threw herself into it. When she came into possession of a children’s atlas, she insisted on waking her sister up every morning to help her find mountains, rivers, and capitals. Which is kind of cute, as long as that sister had her morning coffee.

Shyness continued to be a roadblock for Clara. We’re talking painfully, cringingly, ‘if you laugh at me I will throw up and die’ kinds of shy. Her teachers tended to love her; they gave her all sorts of extra lessons in things like astronomy and poetry, far beyond what the rest of the class was learning. But she was one of those kids who’d rather eat lunch with her teacher than face the cafeteria and kids her own age. It can’t have helped that she was always straining at the edge of her seat, waving her hand around, and struggling with a slight lisp. Once, Clara gave the answer to the teacher’s question about Egyptian Kings as follows: “Potlomy.” The older kids started giggling when the teacher told her that it was ‘Tolemy’. She burst into tears and left the room. DRAMA.

For a woman who would become a teacher, a battlefield nurse, and a lecturer, this whole side of her young self is so interesting to me. Even later in her life, she wrote:

“To this day, I would rather stand behind the lines of artillery at Antietam, or cross the pontoon bridge under fire at Fredericksburg, than to be expected to preside at a public meeting.

”

But luck swept in around age eight, when the family moved onto a bigger farm after her uncle Jeremiah Learned died. Clara found herself left to run wild with her many cousins, which drastically improved her social skills. They explored caves, rode horses, ran across logs in the mill stream - that’s some dangerous business. But even then, she was still looking for the approval of adults. When a painter came by the house to do some work, she asked if she could be his apprentice. He taught her how to paint, to prepare oils, and make putty. Think of yourself at eight. How many minutes would it take before you got bored with this game? But she was a diligent worker. She even varnished the dining room chairs. Can you varnish chairs? I’m not sure I can.

Her Puritan blooded dad was not a fan of dancing, singing, or general wildness in his family circle, so she was forbidden to do any of those things, but one Sunday a bunch of kids convinced her to sneak out and go skating. To teach her how, her cousins tied scarves around her waist and pulled her along, which inevitably ended in two bloody knees and a pronounced limp. She was so afraid of her parents disapproval that she did what she’ll often do in later life: hid her ailments. It took several days for her parents to discover her ailments.

As she got a bit older, her parents realized that maybe they hadn’t been paying her enough attention - Clara was getting a little too wild for her own good. Her mom worried she wasn’t learning how to be a proper lady. So she started pushing her to make girlfriends and hosted little tea parties. Clara was confused. She got praise for being strong and smart and capable of varnishing chairs a few years ago, and now she’s getting censured for it? She had run into the Victorian Tomboy Conundrum: what was cute when she was little became improper when she was a teen. There was danger in her predicament: if you don’t fit into the female mould society has cast for you, then you risk being an outcast; fit in, and you’ll be forced into a kind of life you may not want. A problem that MANY of the women we’ll meet will have to deal with.

When Clara was 11, tragedy struck. Her brother David, ever the wild man, went to a barn-raising, where a bunch of people came together to construct a barn, and he fell. Hard. The doctor prescribed cupping and leeches, which helped turn his general aches into an illness so bad he couldn’t get out of bed...for TWO YEARS. Clara was his nurse for the duration, dedicating herself completely to his care. Her family watched as Clara “became schooled to handling the great loathsome crawling leeches which were at first so many snakes…” He didn’t get well again until after a regime of many steam baths! Who knew you could steam yourself back to wellness? Maybe it helped that all that steaming also came with rest, good food, and a break from the leeches.

Clara loved being a nurse: she was good at it, and it gave her purpose. But taking care of Stephen took a toll on her. At 12, she actually stopped growing. Clara was very good at taking care of others, but often not good at taking care of herself. As a teen, Clara continued taking care of other people, nursing the poor, volunteering, and doing some work at her brothers’ mill. But her shyness and extreme sensitivity were still debilitating. Her parents were perplexed: what to do with her? Luckily, they had an interesting house guest.

L.N. Fowler was an expert in phrenology: that’s the popular 19th-century art of feeling head lumps to determine someone’s strengths and weaknesses. It seems silly now, but this practice was cutting edge for its time, and signaled the beginnings of psychology. It helped spawn terms we still use, like ‘highbrow’, ‘lowbrow’ and ‘well rounded’. And it was generally pretty friendly to women’s rights, as it acknowledged that women had the same potential for mental acuity as men. Well, except for the phrenologists who insisted that feeling lovely lady head lumps provided evidence that women were made for things like morality, kindness, and religiosity. But anyway.

What he had to say turned out to be uncannily foreshadowing. “The sensitive nature will always remain,”he proclaimed of Clara. “She will never assert herself for herself; she will suffer wrong first. But for others she will be perfectly fearless. Throw responsibility upon her.”

So it was decided, to her horror, that she should be a teacher. At 17, she took charge of her first classroom in a local school. It included 40 students ranging in age from 4 to 13. Please imagine, for a moment, the potential madness of a classroom full of 40 kids, all of wildly different ages, for a new teacher with no training who’s barely older than some of the students. I’ve been a teacher and, unlike Clara, love performing, and this scenario makes me want to hide and maybe cry. She was so scared on her first day she couldn’t speak--so she got them to read a passage out of the Bible and asked them to tell her what they thought it meant.

The younger kids were ok, but those four big boys with their arms crossed in the back...they were trouble. They’d bodily thrown their last teacher out of the school and locked the door. So how’s this for some bravery - when they started playing some rough game during one of their breaks, she joined in. "When they found that I was as agile and as strong as themselves," she said, "that my throw was as sure and as straight as theirs, and that if they won a game it was because I permitted it, their respect knew no bounds." Pretty smooth, Clara.

The boys thought this was the best thing ever, and by the end of the term she was a huge success. Her classroom was so well behaved that she got an award for discipline, which she objected to: she hadn’t HAD to discipline anybody, thank you kindly. And then someone explained the award to her, and she was like, OHHH. Cool.

For more than a decade, she was constantly in high demand, teaching in every season. Neighboring towns begged her to bring some discipline to their ‘trouble schools’. Though she never found them all that troubled. Well, except for one time, when a boy was so bad she had to break out her riding whip, crack it once or twice, and then trip him with it. But don’t worry: the class got a nice picnic afterward! She even founded a school for workers’ children at her brother’s mill. She was so well thought of, and knew enough of her worth, that she declined one teaching job when they refused to pay her as much as their male teacher got.

“I may sometimes be willing to teach for nothing, but if paid at all, I shall never do a man’s work for less than a man’s pay.”

This, in the 1850s.

She dedicated herself to teaching, and loved watching her students grow. She did the things I’ve always loved in my favorite teachers: she set the bar high, and insisted they had what it took to meet it. But she found those years exhausting. And there was no chance for further study, for advancement. Clara yearned for something more.

So at 29, she left Massachusetts and went to the Liberal Institute in Clinton, New York. This was one of maybe three colleges that accepted women, just by the way. Being a mature-age student, she didn’t exactly hit it off with the rest of the student population. So once again she was that kid who mostly talked to the teachers, kept to herself, and studied too hard. Like, way too hard. Clara was not going to parties or watching Netflix. One of my very favorite podcasts, the History Chicks, compared Clara to Hermione Granger, and I’m not sure there is a more apt comparison. She kept going to the teachers to ask for more work, taking on pretty much every course available. One of them, Louise Barker, was so concerned about her bookishness that she hatched many schemes to lure Clara out of the library.

But yes, since you’re wondering, Clara DID have gentleman callers throughout her 20s - and by that I mean men who wrote her letters and took her on horseback rides. This is the 19th century. There were a few she’d known back in Oxford, including cousin Jerry Learned (you know, whatever). There was a math professor, Samuel Ramsey, who Louise Barker used as a part of her schemes to get Clara a social life. Another guy courted her, and when that failed, he went out to the goldfields and sent her back $10,000 of his riches. Their correspondence about it can be summed up like this: “um, yikes, well, this is awkward. I’m not really into you, so...take this back?” And he was like, “sigh. I’m sad. But you know, just keep it.”

She had esteem for these suitors, but she couldn’t commit to any. As one friend said, “Clara was herself so much stronger a character than any of the men who made love to her that I do not think she was ever seriously tempted to marry any of them.” If she found someone with a bigger personality than hers - someone who could match, or even outdo her, then maybe she’d think about it. But if she did, I think she knew that being a wife wouldn’t satisfy her grand ambition. Your classic Catch-22 dating situation. And so in a time when marriage was considered a woman’s highest calling, and the most certain way to her financial security, Clara stayed single. Clara, who was not independently wealthy - not even close. A brave move, in this era.

Despite appearing cheerful and calm and gallivanting on horseback, Clara wasn’t having an easy time of it. Her brother Stephen was embroiled in an embarrassing legal case in which he was implicated in a bank robbery. Her mother was ill, and then died suddenly, and Clara didn’t have enough time to get home for her funeral. Despite many letters home, she felt lonely, plagued with self-doubt and depressed thoughts.

Some of these thoughts, it seems, had to do with her year of schooling ending, and the uncertainty of what she was going to do next. Clara was always happiest when she was working herself into the ground for a cause she believed in, and unhappy when she felt idle and without a clear purpose.

So school ends. What to do? She didn’t want to go back to teaching in Oxford. So she went to visit a good friend in Bordentown, New Jersey. During her walks through the streets, she started noticing wild, dirty, boys. A lot of them. “I found them on all sides of me. Every street corner had little knots of them idle, listless, as if to say, what shall one do, when one has nothing to do?” They would be happy to go to school, they told her, but there wasn’t a public one for them to attend. So, in very Clara fashion, she turned her vacation into a work opportunity. She went to the chairman of the school committee and told him that she wanted to open a school for these boys. He was nice, but essentially canned the idea. His list of objections were as follows:

These boys are more fit for the prison than the schoolroom.

The parents won’t like your free school charity. It’ll insult them.

The community, and other teachers, will shun you. They don’t know you.

A strong, local man teacher couldn’t do this. And well, you’re a woman!

She told them thanks kindly, but I’m going to go ahead and do it anyway. I’ll use my own money (I’m hoping it was the jilted lover’s oil field money). But I’d like your blessing all the same. They reluctantly gave it, found her a run-down brick building, fixed it up a bit, and left her to it.

Step right up, boys! Let's get to learnin'.

Clara Barton's school house (taken later, between 1919 and 1929). Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

On her first day, she found just 6 boys sitting on the fence, looking like a bunch of birds who would fly away at any moment. She pointed out plants and birds to them, all casual, ‘stay or go, no big deal, whatever’. They followed her into the classroom, where they started asking about the big map on the wall. It turned out they were bored with all their idle riff raffing: they wanted to learn. By day 2 she had 20 students, and by the end of the week she had 40. Before long, the school swelled to 600 boys - and, eventually, even some girls. She had to turn them away, there were so many. But the committee told her they were worried about her safety. These kids were criminals, after all.

So Clara put the case to the classroom, in a way the teacher in me loves so very much. “Now boys. You see the reputation you beat among the best people of the town. You must either remain as you are or redeem yourselves.” And so they did. She hired more teachers, and the shocked committee built her a new building. The project was a success, and entirely hers.

Satisfied with how things were going, she went home for a summer break. And what did she find, upon her return? That the town had hired a new, male principal. But don’t worry, they told her - you can stay on and be his assistant, mkay? We’ll still pay you a salary - less than half as much as his! That’s cool, right? She did stay on for a bit, but Clara was NOT down with this development. After building up this school from nothing, she didn’t need anyone to “give me directions and tell me what I shall and shall not do.” Especially The Critter, as she called the new guy, who didn’t like any of her ideas and was generally kind of a boob.The faculty frayed, tensions grew, Clara’s voice gave out. She was ill and stressed and completely exhausted. So at 32 she left the classroom, not knowing she would never teach again.

What else is an unmarried girl to do? If she wasn’t going to teach, there weren’t many options open to her. Nannying, domestic work, factory work, or marriage: thumbs down. But a friend was moving to Washington, so she decided to go too - because, why not. At first, she just wanted to read and chill. But we already know she was terrible at chilling, and anyway, she needed money. So she went to her local Congressman, Colonel Alexander de Witt, and was like, ‘hey, could you kindly find me a job?’ - as you do! And thus, in 1854, she became one of the first female clerks in the U.S. Patent Office.

This is a time before typewriters, remember, so she was copying out patent applications by hand. Charles Mason, the commissioner of patents, appreciated her excellent, easy to read handwriting. He also enjoyed her excellent conversation, keen political mind, and discretion when it came to confidential papers. So he offered to pay her $1400 - the same salary as the male clerks working around her. This at a time when there were less than 600 women in the entire country working in a clerical position, AND most working women were making less than $200 a year.

And she liked the work. At that time, the Patent Office was part office, part museum, full of interesting artifacts, bright ideas, and inventive people. The city, too, was growing on her. It was a little wild and stinky, but it was full of intellectuals. She attended small parties, called levees, and made frequent visits to the Senate to sit in the gallery and hear politicians speak. She was busy, felt useful, and was being praised for her work: the Clara Barton Trifecta of Happiness.

But her job was far from stable. Such appointments were often temporary, and depended on who was in charge and what your politics were. Plus, she was a woman in a male-dominated world. Many of her co-workers did NOT enjoy the presence of a woman in their midst who was being paid as much as them. Take Secretary of the Interior Robert McClellan. When Charles Mason left to go back home to Iowa, McClellan immediately demoted Clara to copyist, earning 10 cents per every 100 words she copied. You try writing out a 1,000 words by hand, and time yourself. How long did it take you to earn $1.00? Even a workaholic like Clara could only earn $900 a year this way, a big pay cut, and that’s only if she was given work to do. Some months, she wasn’t given any.

Then Mason came back to the Patent Office, and she became a bit of an office mole, helping him find out who the bad apples were and cut them. This is where we see some of Clara’s very best, and, to me, most challenging, qualities. She was so smart, so driven, so ready to help and be useful. But she was also your classic know-it-all: she liked to show people up, and she was being a bit of a tattletale, for better or for worse. Her co-workers could not BELIEVE a woman was trying to get them fired, and they tried to make her as uncomfortable as possible. They spit tobacco juice on her dress, blew smoke in her face, and made up stories about how many men she was sleeping with. HARLOT. Gross. She persevered, but the job lost its shine.

Meanwhile, tensions in Washington were high over whether or not slavery should be allowed to expand into newly admitted states. In 1856 she went to see politician Charles Sumner give a blazing speech against the spread of slavery. It was so incendiary that, the next day, Congressman Pierce Butler almost beat Sumner to death on the Senate floor. Yikes. It was amidst this climate that the administration changed and she found herself out of a job. She went home for a while, painted, took French lessons, and burned through her savings trying to help out wayward family members, but she felt frustrated and lost. And for anyone who’s been forced to move back home as an adult and live with your parents, you know this is...not a great situation. Her confidence plummeted. She’s staring out her childhood window, wondering if this is it for her. So it was with some relief that Abe Lincoln was voted in as president in 1860, and she got her job back.

When she arrived in Washington, she found it buzzing with war talk. Everyone was talking about how South Carolina had seceded from the Union, and whether there was going to be a war. She thought the extremists on both sides were being too hasty: slavery should be gotten rid of slowly, over time, not all at once like the abolitionists wanted. Better for everyone to calm down and work together. It must be noted that she wasn’t a blazing abolitionist - not yet - and she was in the majority in her beliefs.

But like it or not, war was coming. On April 14, 1861, Fort Sumter was attacked. On April 15th, Lincoln put out a call for 75,000 volunteer troops to come to Washington. Four days later, while changing trains in Baltimore, Maryland, some troops from New England were attacked by a Confederate mob. The Baltimore Riot killed three soldiers and injured almost 40, making them the first casualties of war. The government was not AT ALL prepared to deal with soldiers, wounded or otherwise. They had no barracks or army hospitals, so they ended up putting them in places like one of the Senate chambers. Clara went to see if there was something she could do for them, and what did she find but a whole bunch of former students. It moved her to see them confused and anxious to know what was happening. They only had one Worchester newspaper among them, so they asked Clara - who would rather be shot at than speak in public - to stand on the podium and read it. Which of course she did.

This was a life-changing moment for Clara. These boys, her boys, had almost nothing. No beds, no changes of clothes, not enough rations. If the Union was this ill-equipped now, before the fighting had even really started, what would happen out on the battlefield?

Over the next few months, Clara spent a lot of time with her old students in their makeshift, dirty, disease-ridden camp. Soldiers must have written home about her, as she started receiving supplies from their families through the mail. She got so much she had to move into a warehouse-like apartment, but she was happy to be distributing supplies where they were needed. It was something she could do to help.

And then she watched, horrified, as soldiers staggered back into Washington during what was called the Great Skedaddle, which happened after the Union’s defeat at the First Battle of Bull Run. Some of the wounded lay out in the field for days before anyone found them; those that got back had to wait for any medical attention. She helped nurse one guy who’d been sick with fever for six weeks, with no one tending to him - his sister had to ride out to the camp and nurse him herself. His skin was falling off, and he was starving - literally. So she started actively writing her friends back home, begging them to send supplies.

“It is said that the army is supplied...but in the event of a battle, who can tell what their necessities might grow to in a single day?”

It became clear to Clara that these soldiers needed a middle woman. Someone to stand between the front and the hospital, the bullet and the surgeon. From the minute they were injured or got sick, they were a ticking time bomb. The army didn’t have it handled. But they also did NOT want women at the front, and that’s where she was determined to go. It was one thing for women to nurse in city hospitals now and then. But to go out to a battlefield and attend to strange men in dirty tents? Prostitution! I cannot stress enough: in the beginning, this was seen as outrageously unseemly. And so Clara, quite rightly, was nervous about it.

“I struggled long and hard with my sense of propriety,” she wrote, “with the appalling fact that I was only a woman whispering in one ear, and thundering in the other, the groans of suffering men dying like dogs...I said that I struggled with my sense of propriety...I am ashamed that I thought of such a thing.”

She decided to leave her position at the Patent Office to dedicate herself to her new distribution agency. But they held her job and paid her a partial salary for the duration. A woman working in a government agency AND granted paid leave - was that ever an exception to the rule.

But you couldn’t just swan on over to the battlefields: you had to get passes, or else you wouldn’t get through the picket lines. She pressed her connections and her friends, and got nothing. She wrote strangers, and got nothing. And then she found out her father was dying.

She went to his bedside, telling him all about her plans and fears. It was her ex-soldier father who convinced her to go to the front. He’d been a soldier - he knew their minds - and he knew that they would respect her. When he died, she still didn’t have passes, but she knew her course.

“This conflict is one thing I’ve been waiting for. I’m well and strong and young - young enough to go to the front. If I can’t be a soldier, I’ll help soldiers.”

She went to see Colonel Rucker, the quartermaster. When he asked her what she wanted, she burst into tears. And like it or not, that approach worked for Clara! He gave her passes and ordered her wagons, becoming the first woman to be officially given that blessing. On August 1862, she loaded up a wagon with a couple of ladies and headed for the field.

She arrived four days after the battle, at a depot where they were laying out wounded to wait for the next train to Washington. She watched as wagons dumped load after load onto fields laid with straw, like they were barn animals, their bodies packed together so tightly that she was terrified she’d step on one. She thought she was prepared for this, but she wasn’t. The army was out of everything - bandages, shirts, clean water, you name it - and she brought with: two water buckets, five tin cups, one camp kettle, one stewpan, two lanterns, four bread knives, three plates, and a two-quart tin dish. Clara and her ladies were “a little band of almost empty handed workers, literally by ourselves in the wild woods of Virginia with 3,000 suffering men crowded upon the few acres within our reach.” Those 3,000 men were thirsty, hurting, starving. It wasn’t just that they didn’t have water. It’s that they didn’t even have cups to drink water with. This was life and death, playing out before her eyes.

So they handed out tea, put socks on wet feet, and covered bodies with blankets. This was some of the first attention they got after this battle. Some of them cried when she knelt down next to them. “I never realized until that day how little a human being could be grateful for…” she said. “The bit of bread which would rest on the surface of a gold eagle was worth more than the coin itself.”

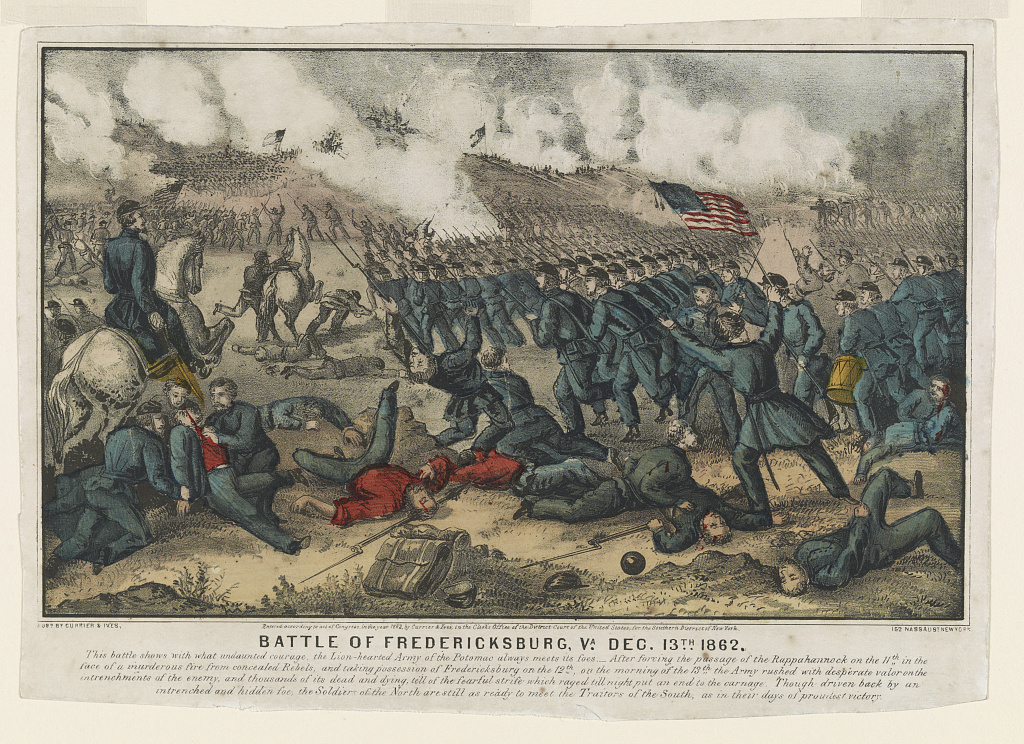

Several battles happened in quick succession in these months of 1862: Cedar Mountain, the Second Battle of Bull Run, Chantilly, Fredericksburg. Clara Barton was at them all, and had to harden up very quickly to attend to the soldiers she called “her boys”. In our last episode, we discussed the horror of Civil War wounds. Now imagine seeing them fresh, just after a battle; imagine that these boys were once students of yours. Because that’s literally what happened to Clara. After the Battle of Chantilly, she bent down over a pale boy with a mangled arm to ask what she could do for him. To her surprise, he threw his one good arm around her and starting sobbing. “And do you know me?” she asked him, kinda shocked. He sobbed that he was Charley Hamilton, who used to carry her satchel home from school. The thought of having one my old students sobbing on my shoulder with a missing arm is...well, it’s a little much for me. “Oh what a place,” she lamented later, “to meet an old time friend.”

Sometimes the greatest, and hardest, gift she could give was her emotional strength. To stand in for the mothers, sisters, and wives that dying soldiers desperately wished they could see. One day a surgeon came to get her: he said there was a boy who was dying, mortally wounded in the stomach, who wouldn’t stop asking for his sister Mary. Would she please go and see if she could calm him down? So she went and found him screaming: “Mary! Don’t let me die alone!” And so she shooed all the doctors away, turned the lamp down low, and pretended to be Mary. He threw his arms around her neck and cried into her hair. “I knew you’d come. I have called you so long.” He was only supposed to last an hour. But when morning came, he was still alive, and thanked Clara. He knew he was dying, and begged her to make sure he got put on the train headed back to Washington. She said she couldn’t make them put him on; those trains were for those who might survive, and he wouldn’t - but he was his mother’s only son and had promised her that he would make it home, dead or alive. So Clara fought to have him put on a train. Many days later, she found him again at a Washington hospital. He’d lived long enough to reunite with his mother and sister, who held his hand before he died.

That’s what Clara had to deal with, again and again.

And it’s not like being a field nurse was a day job. She wasn’t working hard all day, then retiring to some nice little cottage at night. She often slept in the field, in muddy tents and on straw pallets, and ate what the rest of the soldiers ate. This woman would never - ever - ask for anything to ease her pain or give her comfort. She’d rather chatter all night in freezing rain than ask anyone for a blanket.

As 1862 rolled on, she developed a system: find out where a battle was happening, go out to the front, come back to Washington, sleep for a day, repeat. She got more efficient at predicting where a battle would happen. It probably helped that she had friends in the government, and that the army officers were getting more and more grateful to see her heading out to the field. She discovered that, if she got caught behind the army’s long train of supplies and wagons, she’d get to the battle way too late to be of use. So she picked up a new mantra: “follow the cannon.” If she followed the cannons instead of the supply train, she’d be there when the action happened.

The consequence of her new mantra was that she was at the front, on the battlefield, for some of the war’s bloodiest battles. And unlike some nurses, she treated soldiers no matter which side of the war they fought for, which was a somewhat novel idea for the time. But even as she got more famous, there were people who thought her whole enterprise was pretty unseemly. It wasn’t proper for a woman to go out into the field. It wasn’t womanly! A woman with less conviction might have buckled. But Clara responded:

“...if you chance to feel that the positions I occupied were rough and unseemly for a woman – I can only reply that they were rough and unseemly for men.”

There were other women who went out to the battlefield, but not many. Often, she was one of the only women to be seen. Like at Antietam, where 7,280 Union men were killed...and that’s just during the course of one morning. 40,000 soldiers died in total. Imagine that: thousands of guys in a ruined cornfield, all screaming for your attention. Of tending to the wounded there, she said: “I was faint, but could not eat; weary, but could not sleep; depressed, but could not weep.”

But Clara didn’t have any time for weeping. It’s at battles like these that she really earned her nickname, The Angel of the Battlefield. She showed up with chloroform and bandages just when it seemed like surgeons were going to have to start wrapping wounds in corn leaves; when a surgeon had just two inches of candle left to operate by, she came in with scores of lanterns. To the people she rescued, it seemed like she was everywhere.

But even angels bleed. At Antietam, she bent down to give a soldier some water. As she helped him up, a bullet passed through her sleeve and into him. He fell dead, right in front of her. All she could think to do was get up and move on. Another time, she found a soldier groaning with pain. He had a bullet buried in his right cheek, and the surgeons were busy: couldn’t she just get a knife and dig it out? Mind you, she didn’t have any official doctor training. But he really, really wanted her to do it, so she just went ahead. “I do not think a surgeon would have pronounced it a scientific operation,” she said, “but that it was successful I dared to hope from the gratitude of the patient.”

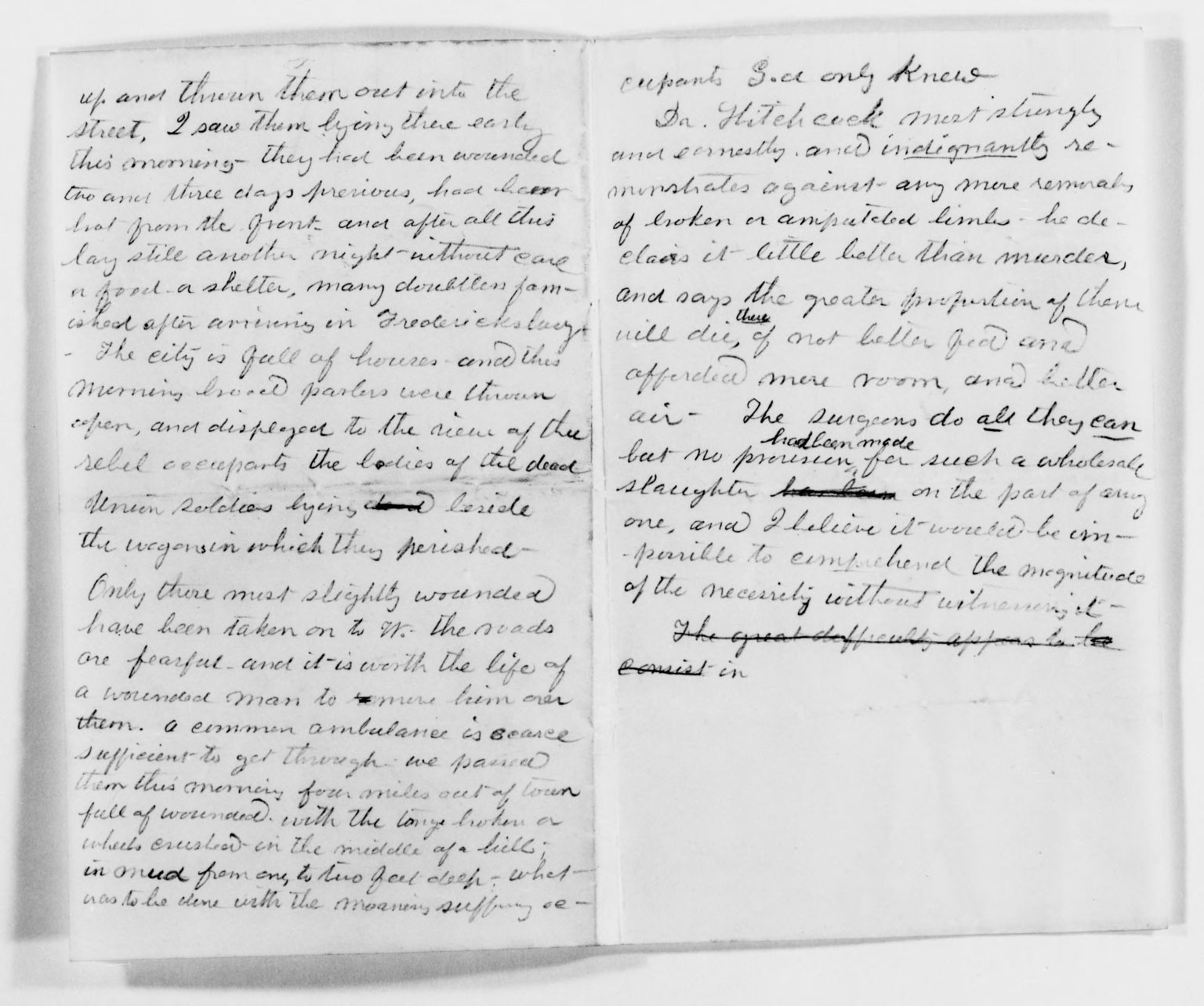

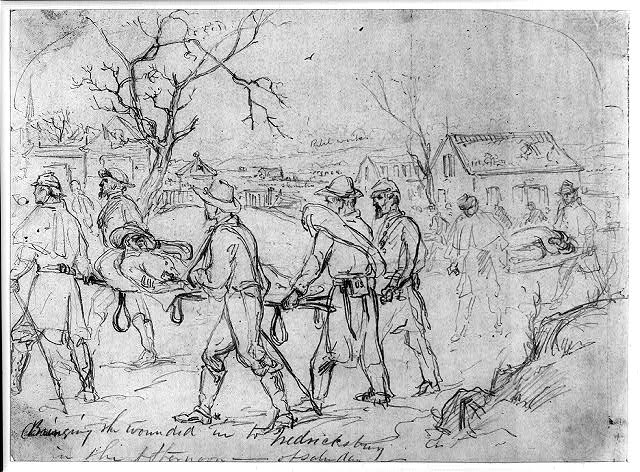

At the Battle of Fredericksburg, Clara saw the most intense fighting of her nursing career. As the Union loitered, trying to finish building a pontoon bridge to cross the river, the Confederate army took up posts in every window. So when the Union soldiers started trying to come over, they picked them off. Thousands of them. She was either insane, or much braver than I am, because when a surgeon wrote her a note begging her to come into the town, she did it. She crossed in a boat, with snipers shot pinging all around her. Guys were shot right in front of her. What she found was “a city of death, the roofs riddled by shell, its very church a crowded hospital, every street a battle line, every hill a rampart…” A rider, who saw her and assumed she was a civilian, was incredibly shocked by her unseemly presence. “You are alone and in great danger, Madam,” he said, all gallant like. “Do you want protection?” She replied that she believed herself “the best-protected woman in the country.” The gallant old dude had to admit she was right.

But this battle was really gruesome. She spent most of it in an old plantation called the Lacey House, which was so full of the wounded and dying that they were lying under tables, on the stairs, and leaning up against corners. The steps of the mansion hosted a pile of amputated limbs. She often had to stoop down and ring blood out of the hem of her dress - let me repeat. Ring blood out of her dress, and keep on going. I’d like to emphasize again that she wasn’t a trained nurse, used to combat. She wasn’t technically in the military at all. She was just a civilian woman trying to lend a hand, surrounded by bullets and the dying.

So it’s no surprise that after Fredericksburg - after five months of near constant nursing - she went back to Washington in a bit of a daze. She looked in the mirror and found herself:

“...shoeless, gloveless, ragged, and bloodstained, a new sense of desolation and pity and sympathy and weariness, all blended, swept over me with irresistible force, and perfectly overpowered, I sank down...and wept as I had never done.”

She let out all of the tears, all the despair, that she couldn’t let herself feel in front of the soldiers. When she finally got herself together, she opened up a mysterious box that had been delivered. She assumed it would be filled with supplies for the boys. But they were supplies for her: dresses, handkerchiefs, linens, collars. It overwhelmed her so much that she sobbed all over again. “...a new cord was struck; my labors, slight and imperfect as they had been, had been appreciated; I was not alone…”

In 1863, she decided to go further afield to South Carolina. She was pretty famous by this point: she could go where she wanted, and men saluted her when she went by. It wasn’t that busy a time for her, in the realm of nursing, and she guiltily enjoyed daily rides with the many officers wanting the privilege of her time. One of these was a certain Colonel Elwell. They rode horses together, shared books, and talked late into the evening. Maybe VERY late. Some of their notes suggest a friendship with just a little side of steamy. In his notes to her, in which he called her Birdie, he’d beg her to come and visit his room. “I cannot forget the expression on your face while we were talking. It was the expression of happiness, the deepest happiness, not the evescent flash of joy, but the deep realization of what only comes to us now and then. Was I mistaken? Was it but a reflection of what I feel in my own heart? I think not.” Oh my! But alas, her dear friend Elwell was married. So whether or not there was steam there, it was always going to end in friendship.

Meanwhile, things weren’t going as well as she’d hoped with her and the army. While she had some friends in high places, there were others who didn’t like her bossy bootsing, her demands and her criticisms. They commandeered her tent to try and get her out of there, and the official army hospitals didn’t want her either. Clara was industrious, and very driven, but she didn’t always play well with others, particularly when those others wouldn’t let her set the rules. But she also held people to high standards, and was upset when they couldn’t, or wouldn’t, meet them. She left the South deflated and depressed. Again.

But then in 1864, she was finally given an official position in the army, made head nurse in charge of diet and nursing at an X Corps hospital near Point of Rocks, Virginia, in the employ of Major General Benjamin F. Butler. We will learn more about how Benjamin “Beast” Butler sucked in some respects in later episodes: let’s just say he was a man of extremes, and not a fan of mouthy southern ladies. But he loved him some Clara, make no mistake.

Clara was in charge of what was called the "flying hospital", a traveling tent city that moved with the army. One of her biggest contributions here was in the realm of nutrition. Food was often scarce, and a very far cry from nourishing. So Clara busied herself making things like pies, gingerbread, and roast beef. She also found some codfish, which apparently reminded the New England patients so much of home that they burst into tears over it. Codfish. Mkay.

But she was worried about her brother Stephen. For years, he’d lived and made his living in South Carolina. She and the family had begged him to leave the South while he still could, but he refused to abandon everything he’d worked so hard for. Clara hoped that, being closer to him, she could find a way for the Union to rescue him. Instead, the Union arrested him and threw him in a prison cell. Drama. He was treated really badly in Norfolk, VA, refused medicine and adequate food. But Clara got Benjamin Butler to save him. Clara to the rescue! But even then, Stephen wasn’t doing well.

So in the early months of 1865, Clara went back to Washington to nurse her brother and a young cousin who’d been slowly dying of consumption. She lost them both, and was devastated. The war ended in April, and Clara was once again at a loss and an all-time, black cloud low about her future.

But a current event pricked her interest. Now that the war was over, soldiers who had been kept in southern prisons were slowly starting to trickle back into the North. They needed food and clothing, and help getting in touch with their relatives. But it was more than that: so many men were missing. She’d been keeping lists of names and addresses in her diary - the boys she’d met who wanted to make sure she wrote to their families in case of death. So she applied for and won the approval of Abraham Lincoln to address the problem of missing soldiers. That permission was one of the last pieces of paper he signed before he was assassinated.

When diplomacy fails, be a teacher about it: write the president a very fancy-looking letter. Here is the one Clara wrote respectfully requesting that he 'let' her be in charge of helping find lost soldiers. She even drew lines on the page!

Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

And so The Office of Correspondence with Friends of the Missing Men of the United States Army was born and set up in Annapolis, Maryland. A notice in the newspaper went out saying she was the person to write if you had a family member missing, and missives absolutely poured into her makeshift tent. We’re talking over 63,000 requests in a time well before keyboards or jelly pens: she had to hire some assistants to help her answer them. And, you guessed it, the army wasn’t paying her. They gave her supplies and help with printing her lists of names, but that was it.

Let’s talk about the scope of this project: some half of the Union men known to have been killed were still unidentified. Some 190,000 unmarked graves - almost 200,000 families who didn’t know where their children were buried. She did what she could in the realm of info gathering - she would talk to the soldiers coming off the boats from the South, asking them for any information they had about the men they fought with. She used the press to publish her lists and got people to write in if they had information. In four years, she was able to locate some 22,000 men. A huge number of these were deceased, but at least she could give their families closure. But a few were actually alive and well!

Like one guy, who’d decided to shack up with a Southern lady and start a new life, who wrote to her complaining about his name being splashed about in the papers. How dare she! She wrote him back, that stern teacherly finger wagging: “It seems to have been the misfortune of your family to think more of you than you did of them, and probably more than you deserve from the manner in which you treat them.”

A huge part of that 22,000 located soldiers were thanks to one Dorence Atwater, who’d been a prisoner at the famously terrible Andersonville prison. This 18 year old secretly copied the names, ranks, and cause of death of thousands of Union soldiers while a prisoner, hiding it in his shirt sleeve knowing it could get him shot. He shared it with Clara, and in 1865, they went down to Andersonville, located and marked nearly 13,000 Union graves. That’s 13,000 families that could at least know what happened to their loved one, who knew that they were properly buried. In August, she was asked to raise the US flag at the dedication of Andersonville National Cemetery. Big deal.

But then, just like at her school in Bordentown, the gentlemen took her project from her. She was in their way - they could take it from here, thank you. So once again, she had a problem: she was out of a project. And by the way, she’d finally lost her job at the Patent Office, having not been there in, oh, five or so years, and had spent all of her money funding her initiatives. She was living on less than 50 cents a day. Whoops.

Luckily, a few things happened. Congress appropriated $15,000 to reimburse her for expenses associated with her search for missing men. She also testified in front of Congress about her experience at Andersonville. She not only told them about how horrible the conditions had been for the prisoners, but how terrible things were for African Americans in the South. And thus she became the first woman to testify in front of Congress, fighting against oppression. Yas, Clara.

But what to do now? She needed money and a project. Her friend and fellow nurse Frances Gage was like, “Easy. Do what I do. Start lecturing.” But in the mid-19th century, ladies making speeches was still a little risque, and Clara would rather gouge her own eyes out than speak for a crowd. But in 1866, and for two years, Clara went out on the circuit, giving speeches about what she’d seen during the war. And though she still had morbid stage fright, she turned out to be really good at speech making. She was a big success, thrilling audiences, earning her some $75 to $100 per lecture. She shared platforms with famous people like Frederick Douglass, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Mark Twain. These speeches about her exploits are actually a big part of why she’s still so famous today - girl was nothing if not good at crafting her own public image.

And though she was not ever fully entrenched in the suffrage movement, she did use her fame to try and make some headway for women’s rights. She was particularly well placed to do this because, unlike most women lecturers, many of the people in her audience were men. She told the vets in her audience: "Women were your friends in times of peril. And you should be hers now."

Before one such speech, Clara read an advertisement about it in a local paper. Don’t worry! It promised. She’s not going to be one of THOSE lady speakers who drove on about rights and such. So she marched up to the stage, did her usual thing for a crowd that was mostly gentleman veterans, and then delivered the following zinger:

“You glorify the women who made their way to the front to reach you in your misery, and nurse you back to life. You called us angels. Who opened the way for women to go and make it possible?...For every woman’s hand that ever cooled your fevered brows, staunched your bleeding wounds, gave food to your famished bodies, or water to your parching lips, and called back life to your perishing bodies, you should bless God for Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Frances D. Gage and their followers.”

Damn, Clara.

By 1869, age 47, Clara was exhausted. She’d closed up the Office of Missing Persons, and her hard living, stress, and lack of sleep were catching up. Her doctor advised her to take a break and go to Europe.

Eventually she ended up in Switzerland, which is where she a met a Dr. Louis Appia. And he had a question for Miss Barton: why had the United States not signed on to the Geneva Convention? Why didn’t they want to get on board with the Red Cross? She said she didn’t know: she’d never heard of it.

Well, 32 nations had signed onto the Geneva Convention, which laid out how soldiers were to be treated in times of war. It said that all things related to wounded soldiers had to be neutral, like when you call a timeout in capture the flag. Hospital personnel and nurses should be treated with immunity. The wounded should be taken care of no matter what side they fell on. Medical supplies weren’t to be raided or touched. So basically, everything she’d been trying to do out on the battlefield. This Red Cross thing sounded great!

Whereas I would then have gone to Budapest and spent several years floating in thermal pools, Clara started feeling listless. Lucky for her, a war was about to start. The Franco Prussian War, to be exact. Bad health be damned, she was going to the front with the Red Cross! When she did, what she saw hugely impressed her. They had so many supplies! Things were clean! The medical personnel were trained and treated well! And unlike in the Civil War, no soldier could lie around untreated. It must have been kind of upsetting to think of how many lives such a system would have saved, back in 1861.

But she wasn’t just handing out supplies. In the city of Strasbourg, Clara saw that many civilian women had been affected by the carnage. People were homeless, demoralized. So instead of giving them food, she fell back on her old teaching days and set the bar high.

She bought cloth, made designs, and gave it to these women to sew and either hand out to the destitute or sell to make some money. She didn’t just put clothes on these women’s backs - she helped them do it for themselves by founding workhouses.

But again, Clara collapsed, and was out for the count for several years. Apparently nursing in two wars will do that to you. She stayed in Europe for a while, then came back to America, where she found doctors that did her about as much good as they’d done her brother David. They told her to take three-hour baths, drink rum and cherry cordial. Eventually, she ended up in a sanitarium, or what sounds like a really lovely spa-like place. There she ate things like the original, not nearly as delightful Graham Cracker and a newly invented health food called granola. Eventually, she was well enough to take up a new project. About time, because let’s be honest, Clara, you have been a real slacker thus far in life!

That project would be the American Red Cross. She spent five years working hard, harassing people, and getting journalists and veterans on her side, and handing out pamphlets to anyone who would take one. She was that aunt who won’t stop talking about that thing she’s into. In a time when women weren’t often change makers, especially in the halls of Washington, Clara campaigned tirelessly, mostly alone, wading against the tide of people who might have shut her down. And at long last, on May 21, 1881, the American Red Cross was founded. It was a giant, gleaming, monumental achievement, and it shaped American relief work forever.

But Clara added her own personal twist to the Red Cross, and that was peacetime relief work. It wouldn’t just help in times of war, but in the face of any kind of disaster.

In our century, this organization is huge. In 2016, they gave some 4 and a half million people help after disasters, vaccinated millions of children, trained some 5 million people life saving skills, and donated some 40% of America’s blood supplies. But in 1881, it was just Clara and some buddies making pamphlets explaining what the Red Cross and the Geneva Convention was and passing them out to anyone who would listen.

Clara Barton led the Red Cross for 23 years. It would take a very long podcast to detail all of the things she did in those decades, so let’s highlight some of the most amazing. While the Red Cross was still a relatively small and riches-poor organization, competing with other rising relief agencies, Clara knew that she had to work hard to publicize it. It was only through becoming a national organization that it could be truly effective, and get people to care. She was great at PR: during a series of floods in the South, Barton hired out a big boat and sailed around delivering things herself. Much like she used to materialize out of the mist to deliver chloroform and bandages, her boat appeared out of nowhere, making it seem like the Red Cross was everywhere.

In her quest to make the American Red Cross known, she also accepted an invite to go and talk at an International Red Cross convention in Geneva, becoming the first female diplomatic representative in American history. They were so impressed with what she was doing with peacetime relief that they actually added a new amendment to the Geneva Convention, called the American Amendment. The Clara Amendment would have been cooler, but, ok. Though perhaps this wasn’t her goal, her presence and influence there was a huge coup for women’s suffrage. In the public world still dominated by men, she was speaking in front of large crowds and being listened to, making more headway for women’s rights than many. “Miss Barton has not proceeded to batter down opposing walls with a sledgehammer,” one admirer put it,“but has quietly and skillfully opened a door with a well turned key; it will never be closed.”

She also infused some revolutionary ideas into the relief work of the Red Cross. First, was that everyone deserved their help - no matter who they were or where they came from. The second was that the Red Cross shouldn't just swoop in and take over. Their role was not just to aid, but to help people help themselves for the short and long term.

For example, during the terrible Johnstown flood in 1889, she went out of her way to get to the poorer families that many other relief organizations were ignoring. She worked closely with locals to make sure that no one, no matter their station or the color of their skin, would be ignored. She opened several hotels for homeless people, then turned their management over to local women. She was a big fan of helping people help themselves.

In 1893, a terrible hurricane off the coast of South Carolina absolutely devastated the Sea Islands where Clara had once done some of her nursing. The predominantly African American communities who lived on those islands were left starving and destitute - a condition that, sadly, a lot of Americans turned a blind eye to because, well, racism. Clara Barton, upset by this, went off to help them, with zero government aid and very little money left in the Red Cross purse.

What she facilitated was astounding. She didn’t just supply them with food to get them through the winter. In fact, she would only give them food donations if they planted the seeds she gave them in their gardens, thus ensuring that they’d be able to feed themselves come spring. The harder the local people worked to rebuild, the more rations they got from the Red Cross. It may sound harsh, but the idea was to give the very demoralized locals the power to rebuild their own community, create their own prosperity, in a way that would last long beyond this particular crisis. Take the clothing department she set up, run by local women. They’d take old, donated garments, wash them, then cut and sew them into new garments, which they gave to the very needy in exchange for hot meals. She also encouraged them to plant the specialized cotton that had once made the Sea Islands quite rich and famous. It was hard to find, so Clara harassed the government - she was such an expert harasser! - to obtain it, thus ensuring the Sea Island people would have a long-term and sustainable cash crop.

With little support and a lot of skepticism, she helped get 30,000 people through the winter. Or rather, she helped them get themselves through the winter.

She also got involved in foreign aid. In 1891, Russia suffered a terrible crop failure, resulting in some 35 million starving people. America had never really gotten involved with foreign aid, and decided that they didn’t want to now. So Clara went ahead and did what she did best: took the hell over. The Red Cross, still not huge at this point, made corn donations that fed 700,000 for a month. She got involved in other foreign war conflicts, too, serving in Cuba, the Bulgarian and Serbian War, and the Spanish-American War, because - why not? In many of these conflicts she was once again in the field, making gruel over campfires, and living in a tent: her happy place. Despite the fact that she had to dye her hair to try and hide her now quite mature age.

Clara Barton was an absolute force of nature, but that didn’t always make her a great leader. She saw the Red Cross as her baby, her greatest project, and was very much of the mind that if you want something done, do it yourself. Like, do EVERYTHING yourself. Unfortunately, Clara had never learned to delegate or go with the consensus. She was no longer called the angel by her followers, but the Queen or the Great I Am. Other people saw her as dictatorial. When people offered her suggestions, she took it as criticism and reacted badly. When people disagreed with her, she saw it as treachery. Plus, she didn’t want to sit behind a desk, really. She wanted to be out in the field. Clara just couldn’t let go. And so it was that after a significant amount of pressure from inside the organization and outside of it, she was forced to resign in 1904, at age 73. Her baby was taken away from her. Poor Clara.

Ready to rest after, oh, let’s say five careers, she retired and took up knitting. Just kidding! She wrote a book about her childhood and founded the National First Aid Association of America. She helped create the First Aid Kit that’s probably in your closet. Girl never was very good at sitting still.

Clara Barton died at her home in Glen Echo, Maryland, at the age of 90, after a very long and extremely busy life. “If she had belonged to the other sex,” Henry Bellows wrote of her,“she would have been a merchant prince, a great general, or a trusted political leader.” Note to you, dear Henry: she wasn’t a man, but she still managed to do an outrageous amount. She heckled politicians for policy changes; she inspired hundreds of students, and then nursed them back to health out on battlefields, just because she thought it was the right thing to do. She founded an organization that almost 200 years later, is still one of the most important relief agencies in American history. She did more in her lifetime than most of us could do in five.

She wasn’t an angel - she had flaws, just like the rest of us. But that didn’t stop her from striving, always striving, to find her place in the world, and to do what she could to make it a better place. Of her life’s work she said:

“Others are writing my biography, and let it rest as they elect to make it. I have lived my life, well and ill, always less well than I wanted it to be but it is, as it is, and as it has been; so small a thing,

to have had so much about it!”

Until next time.

Voices

Nancy Wassner = Clara Barton

Billy Kaplan = the charming Elwell

Avery Downing = the dapper gentleman on horseback

Phil Chevalier = Henry Bellows

Music

All of the royalty-free music featured in this episode comes from Audioblocks.