Sarah Emma Edmonds: Soldier, Nurse and Spy

Army Private Franklin Thompson had some crazy adventures in the Civil War.

He nursed hundreds of wounded soldiers on battlefields; rode down dangerous roads through the night to deliver mail. He dressed up in crazy disguises and spied on the Confederate army, sneaking into their camps and back out again unscathed. He fought on through pain, illness, and heartache. And all the while, no one knew that Frank was actually a woman.

This is the story of Sarah Emma Edmunds, who did many wild and adventurous things. She lived for years as a man, served three years as a soldier in the Union army, wrote a best-selling book, and became one of the only women soldiers to get a pension for her military service. In a time when a woman’s role was fixed and certain, she was brave enough to live on her own terms, no matter what it cost her.

Get ready for high adventure, midnight rides, and a potential love triangle. let’s go traveling.

resources

Books

They Fought Like Demons: Women Soldiers in the Civil War by DeAnne Blanton and Lauren M. Cook. Vintage Civil War Library, Random House, 2002. My favorite, now and forever.

She Rode With the Generals by Sylvia Dannett, T. Nelson & Sons, 1960. Though a bit dated in some of its views, this book really delves into the truth behind Emma's memoir, trying to verify and breathe accurate life into the woman behind it. Super helpful in finding out more about the details of Emma's life.

Liar, Temptress, Soldier, Spy by Karen Abbott, HarperCollins, 2014.

Nurse and Spy in the Union Army by Sarah E. Emma Edmonds, DeWolfe, Fiske, & Co., 1864.

The Mysterious Private Thompson: The Double Life of Sarah Emma Edmonds, Civil War Soldier by Laura Leedy Gansler, University of Nebraska Press, 2007.

Online

“Sarah Emma Edmonds (1841-1898).” From "Spies and Spymasters of the Civil War" by Donald E. Markle.

"Sarah Emma Edmonds Seelye." Michigan in Letters.

“I am naturally fond of adventure, a little ambitious, and a good deal romantic, but patriotism was the true secret of my success.”

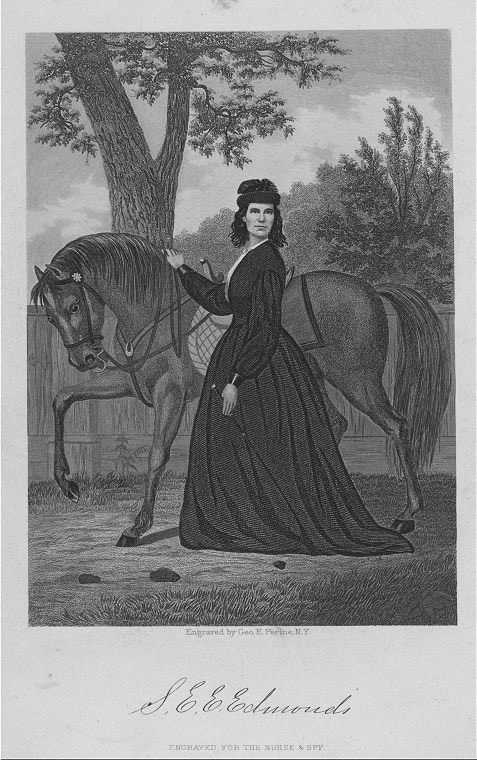

Emma’s image, before life as a man and after. A dashing figure in either set of attire!

Courtesy of the Archives of Michigan.

transcript

keep in mind that this is a rough draft - it won't follow the finished product exactly. i like to edit, correct, and ad-lib as i record.

Sarah Evelyn Emma Edmondson was born in New Brunswick, Canada, in 1841. Her parents, Isaac and Betsy Edmondson, were immigrants: Isaac’s people had originally come over from Scotland. When he decided it was time to find him a wife and have some babies, he plucked Betsy right off an Irish boat. New Brunswick wasn’t an easy place to be a dirt farmer. In this wild, sparsely populated frontier, the winters were frigid, the fogs intense, the soil difficult. So when Isaac married Betsy, he did so with the hopes of fathering a brood of sons to lend a hand. But instead, he got himself several daughters in succession - Eliza, Frances and Mary Jane - and then, finally, came Thomas. But wait...he had epilepsy, which made him a dud in Isaac’s eyes. With each new birth, Isaac grew more bitter and full of rage. So it was that when their last child came along, Isaac was itching for a healthy boy. But he got Emma. He resented them all, but particularly that last one - his last child, his last hope, turned against him. There was a coldness in him, a resentment, that Emma felt all of her young life.

Fanny Campbell, the Female Pirate Captain: A Tale of the Revolution was published in 1844 American by Maturin Murray Ballou. It's about a woman who goes to sea to rescue her fiancé and, delightfully, becomes commander of a pirate ship and free-wheeling lady of pleasure. This heroine continued to be popular long after the book was published, especially in Emma's imagination. Wikicommons.

When Emma was 13, a peddler came by the house and, perhaps seeing a spark in her, gave her a novel. It was the first she’d ever read. Fanny Campbell, The Female Pirate Captain, published in 1844. She was enthralled by how Fanny chopped off her hair, disguised herself as a boy, and went off to sea to find adventure in the great blue yonder. The one thing she didn’t like was why Fanny did it: to rescue a dashing fiancé. In her opinion, that was something to pity her for. “I regretted that she had no higher ambition than running after a man.”

And exciting as it must have been to girls in the Victorian age, the book does conform to the antebellum era’s ideals of womanhood. In the end, after rescuing her lover and the rest of the crew, Fanny goes home, gets married, and takes up her place again in the private sphere. But it’s radical in the way it heralds a woman being assertive and brave. It legitimized the notion that a woman could be virtuous AND adventurous, if she played her cards right. That stuck with Emma. She said that, after reading it, “I felt as if an angel had touched me with a live coal from off the altar….I went home that night with the problem of my life solved.”

She wanted to be a traveling missionary: something that would combine her thirst for adventure with her love of God. But there was one life problem Emma still had to tackle: how to get out of marriage. She’d seen how her father treated her mother, who Emma viewed as a saint. She was his inferior in every way - a servant to be commanded. He often beat her, just like he beat his frail son and his daughters, and chastised her in public. His treatment enraged her, filling her with a hatred of men. “In our family the women were not sheltered but enslaved; hence I naturally grew up to think of man as the implacable enemy of my sex. I had not an atom of faith in any one of them. If occasionally I met one who seemed a little better than others, I set him down in my mind as a wolf in sheep’s clothing, and probably less worthy of trust than the rest.”

But that didn’t matter to Isaac: he planned to marry off his daughters. One by one, Emma watched her sisters sold off. When she was 17, she noticed an elderly, freshly widowed neighbor watching her a little too keenly as she pulled potatoes. Her father noticed, too, and soon struck up a deal with this neighbor. He wanted her married, and wouldn’t hear any refusals. But Emma was having absolutely none of that.

We don’t know how Emma actually made her escape. All we know is that she did it, and dear old dad pursued. But soon she realized that she’d have to go further afield if she didn’t want her dad to find her. But how to get free? This was a time, remember, when women can’t travel by themselves, without a chaperone. Though Emma wasn’t a rich girl; she hadn’t grown up in the cult of true womanhood. But there was a flip side to that coin: Emma was poor; she had no money to run away with. It would be really hard to make a living on her own. At least, one she wanted.

With so much going against her, most women would have just gone home. But Emma did something radical. This girl, alone and still in her teens, put on pants, cut her hair, and made up a new identity: Franklin Thompson. He replied to a job ad as a traveling Bible salesman.

It was the perfect job: she’d be able to travel, and thus avoid her father finding her, and enjoy some freedom. She’d be able to make money of her own. But at first, she was so worried about being recognized that she traveled at night and slept in the woods during the day. Tired and hungry, she knew it was time to try and sell some books. Those first visits going door to door must have been sweat-inducing. Would they see past her clothes and know what she was? But her fears turned out to be unfounded: the strangers bought her persona, every time. Emma was tall for her era, and rather lithe from her years of hard labor. She had a strong jaw and cheekbones - not a delicate flower. She didn’t have any trouble passing, generally. In fact, people tended to take a liking to young Frank Thompson. She outdid most of the company’s other salesman, making enough money to get along quite well. Over the next few years she prospered, buying nice clothes and a horse and buggy. She made mad money and a lot of admirers. She took ladies to balls, drove around with them in her carriage - she even prompted one or two to fall in love with her. Whoops.

How did she pull that off? Well, for one, courtship was different in the 1850s. These dates would have involved little more than closely watched conversation: no one would have been trying to cop a feel. But let’s dig deeper: why would Emma call that kind of attention to herself, when impersonating a man was illegal? It wasn’t very often that such laws were enforced. But there was the risk that she’d be sent home to Isaac, which must have scared her more than anything else. Plus, it must have taken a toll on her soul, to live a lie. She would never have been able to be fully relaxed, or fully honest. So why do continue to do it? Well, because it turns out that life as the enemy was actually pretty good!

But this fortune couldn’t last forever. Something happened: some great misfortune. Emma somehow lost all of her money, left with nothing but her sample Bible and a gold pocket watch. Who even knows what happened to that fancy carriage. Anyway, she found herself with no way to continue working. Broke, she struck out down South for Hartford, Connecticut, home of the Bible publisher whose books she’d been selling.

It was an epic journey that involved walking through feet of snow, cold and hungry, hitching a ride on the occasional horse sleigh. By the time she arrived in Hartford, she was, as she put it, “a stranger in a strange country; a fit subject for a hospital; without money and without friends.” She sold what remained of her valuables, rented a room and a new suit of clothes, took a nap, and trotted off to Hurlburt and Company. She introduced herself - as Frank Thompson, of course, and then “almost in the same breath I asked them if they had any use for a boy who had neither money nor friends, but who was hard to beat on selling books. They laughed a good, hearty, manly laugh...” and so they hired her.

She travelled back and forth between Canada and the U.S. for a while, selling books with great success. During nine months in Nova Scotia, she earned back all of her lost money and then some, and managed to go on more than one date. Though dating ladies in this era had occasionally awkward consequences. “I came very near to marrying a pretty little girl that was bound that I should not leave Nova Scotia without her.” She also earned over $900: $100 a month. Compare that to the 8 to 10 a month she would have earned as a domestic, and you can see how she got over her scruples about her deception!

She travelled West, eventually landing in Detroit and then Flint, Michigan. She was there, in 1860, when the call to arms from President Lincoln came. A war was starting, and she watched as many of her friends joined up amidst the patriotic fervor. Emma found herself at a crossroads: she was Canadian, and a woman, and thus wasn’t required to stay and fight. But she believed in the Union and was against slavery. What part could she play in what she called “this great drama”?

Should she volunteer as a female nurse, or join up as a soldier? If she signed up as a woman, she’d have to give up Frank Thompson - and she’d been him for so long, living the best years of her life. Frank would see a lot more action in the war, and a lot more freedom. Having been living as Frank for a while, she would have felt the same pressure to join up as the rest of the men. There was a lot of it. But was she willing to take her deception to that level? Under the scrutiny of the U.S. Army, would she even be able to pull it off? As a devout Christian, the whole Frank vs. Emma issue must have been a thorny one. So she prayed on it. And 19-year-old Emma decided it was God’s will that she join up.

“I was not able to decide for myself. I carried this question to the Throne of Grace and found a satisfactory answer there.”

It was probably the Throne of Grace she was thinking of as she stood nervously in line at Fort Wayne in Detroit, waiting for the doctor to examine her. As we discussed in our last episode, these exams weren’t often very thorough. They were supposed to be, though: government regulations said that: “In passing a recruit, the medical officer is to examine him stripped; to see that he has free use of all his limbs; that his chest is ample; that his hearing, vision, and speech are perfect…” and so on. But so many people were joining up that they often involved nothing more than a few taps and bumps, clothes left on. The army needed bodies: functioning eyes, some teeth, and enough fingers to pull a trigger. But Emma didn’t know that, and she no doubt would have been terrified. There was a good chance she would be caught, turned away, laughed at, as many of the women who tried to join up were.

When her turn came, the doctor looked her over, then wrapped his fingers around her wrist. Her hands were one of her biggest threats: they were small, delicate, and no longer had the calluses they had when she was young on the farm. Those hands could ruin her.

The doctor looked her in the eye and asked, “what sort of living has this hand earned?” She replied, “that hand has been chiefly engaged in getting an education.” And that was it: Emma was in. Or rather, Frank was in, part of the 2nd Michigan Infantry. She told herself that God approved of her mission and excitedly headed off to Washington City in June 1861 for basic training.

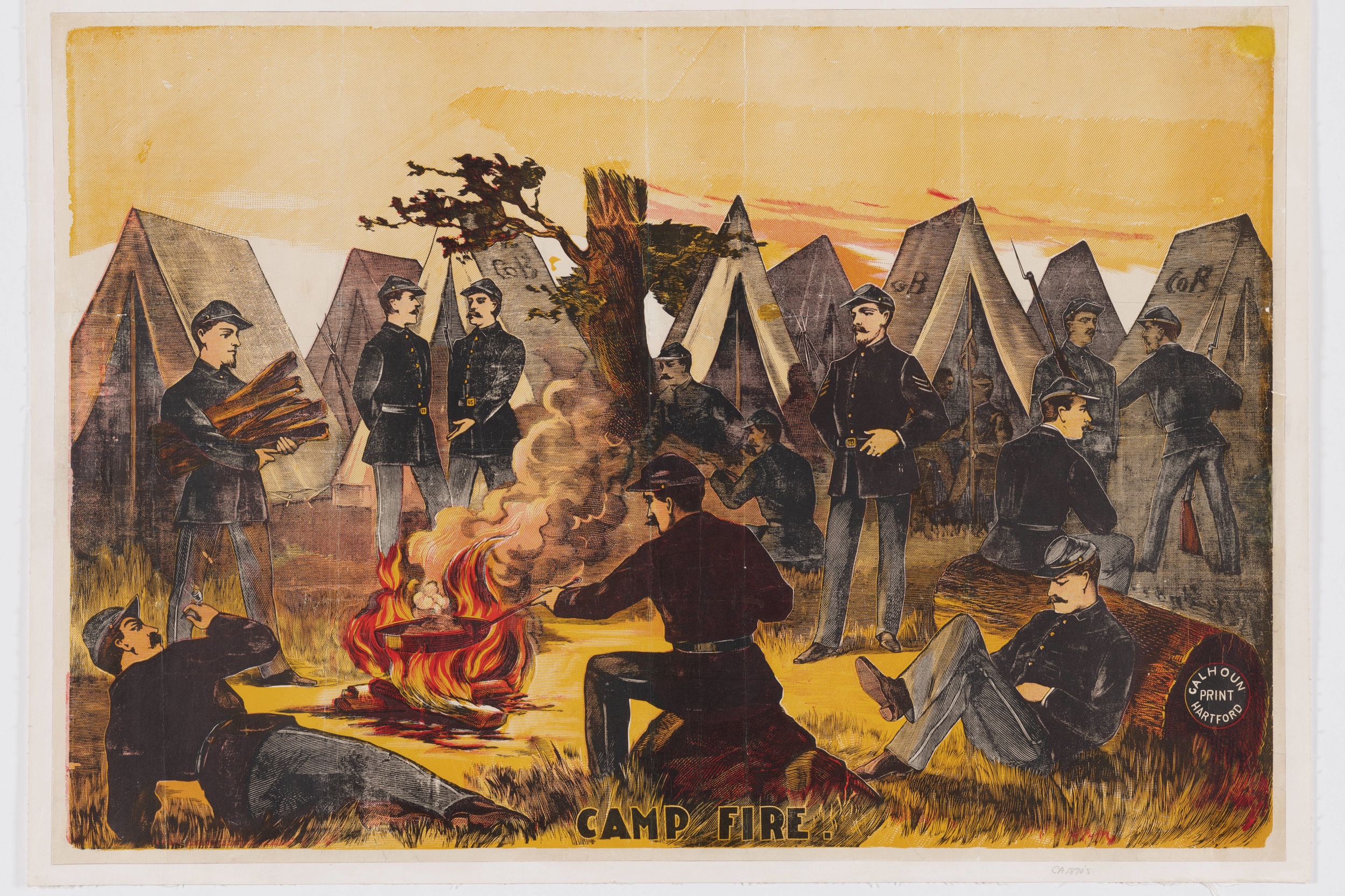

Life in Washington was loud, hectic, and full to bursting with soldiers. Still-green soldiers marched down the Mall; they lounged in Senator’s seats in the Congress building. The tents they stayed in were 7 x 7, made for two to four men. A lot of women soldiers ended up caught at this early stage, failing to pass under such close quarters and scrutiny. These men didn’t know how to mend ripped pants, wash a dish, or do laundry. It was a suspicious amount of knowledge in the domestic arts that got some women caught in the ranks, so Emma dumbed her skills down as much as possible. She had years of practice at being Frank Thompson, and was used to, and enjoyed, hard work, routine and long days.

Hers started at five AM - an early call time that meant, conveniently for Emma, that soldiers tended to sleep in their clothes - with breakfast, then moved on to endless drilling and dress parades in the streets. This was a civilian army, not a professional one. Some of the commanders wouldn’t let them have real bullets to practice with, afraid that they’d all end up killing each other. But Sarah did just as well as the rest, if not better: she could march for days, ride like a pro, and was a whizz with a musket.

There were plenty of reasons she should have been caught: the close quarters, the fatigue, her suspicious adeptness at domestic skills. I mean, her buddies jokingly called her ‘our woman’ because of her voice and her feet, so small that army regulation boots didn’t fit her. It helped that her tent mate, Damon Stewart in Flint Michigan, took Frank under his wing. He assumed that Frank had lied about his age to get into the army, hence his baby face and squeamishness about swearing. His belief meant that others didn’t question. And she had a bit of a reputation as a lady’s man, though these conquests were probably as chaste as they came. Frank was not impressed by the general chaos of the army in these early days, particularly the frequent visits to brothels. God-loving Emma was not into drinking or debauchery, which must have made it difficult for her to blend.

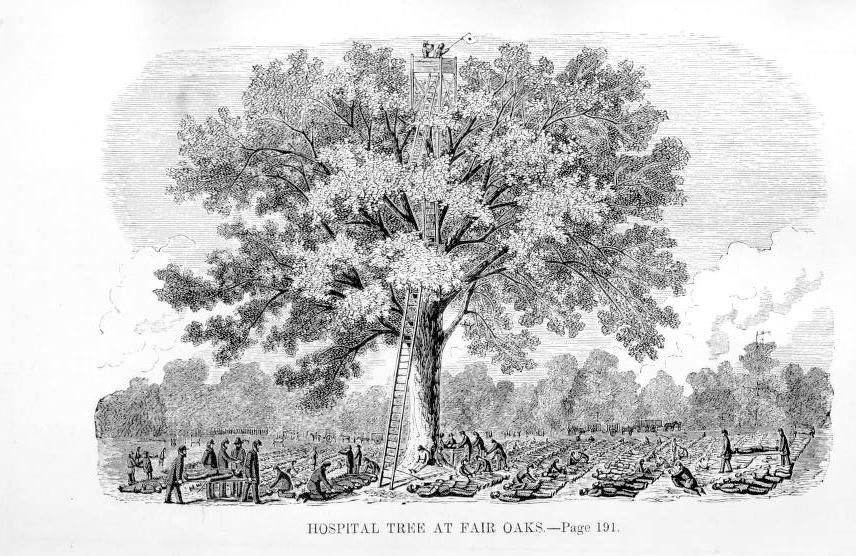

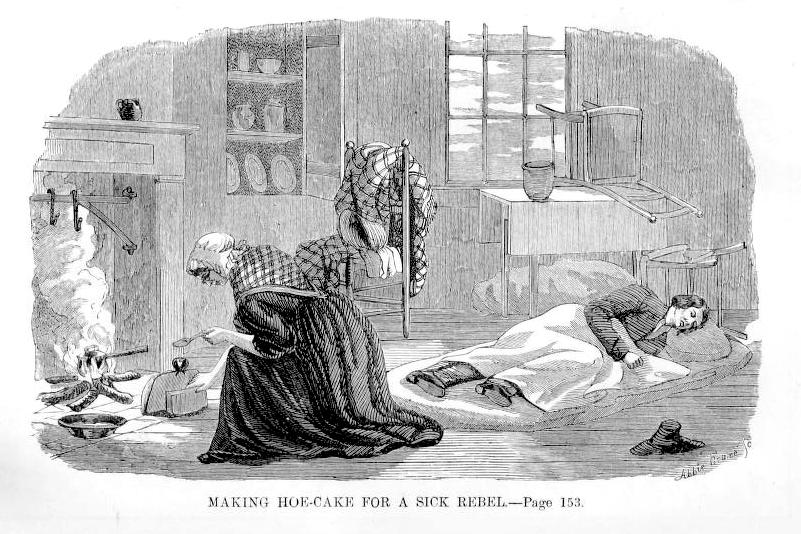

She spent most of her time tending to the sick. There were already a lot of them: some 30% of the Army of the Potomac was sick before they even went into their first battle. Typhoid was carrying soldiers off right and left. She and her fellow nurses did what they could: they put up awnings around the sick tents and planted evergreen trees around them, and dug out pits to try and deal with the torrential rains.

Every day, she waited for their marching orders to come. The papers cried out for action with slogans like: “Forward to Richmond!” Then finally, in July 1861, it came.

They set off with much music and fanfare, but she was dismayed by what became apparent on their march to Manassas, Virginia: even after months of drilling, the army was still a big, disorganized mess. They broke ranks, wandering off to pick blackberries, and stopped frequently to take off their still-not-broken-in boots. The army had roughly 33 miles to travel - back in our century, by car, that would take us less than an hour. It took them several days.

Picture a bunch of office workers strapping on heavy packs and heading down the Appalachian Trail with almost no training whatsoever. By the time they got to the field of battle, they were sunburned, parched, and tired. But they were excited: this was it, at last.

At this point, nobody really knew what they were in for. Spectators drove from miles around to watch the battle, bringing picnic baskets. Everyone thought this war would be one battle and done. Little did they know the shit storm that was about to hit them.

But hit them it did. Emma watched with her fellow nurse mates as things heated up. “Now the battle began to rage with terrible fury. Nothing could be heard save the thunder of artillery, the clash of steel, and the continuous roar of musketry.” Emma watched as men got mown down, officers and privates and helpers alike, legs crushed, arms gone, grass running red. With bullets whizzing around her, she rushed to get soldiers water and to help the wounded get to safer ground.

Let’s skip the ins and outs of this battle in favor of a summary: the Union seemed to be making headway, but then things turned against them. The Confederates rallied; the Union buckled; the very inexperienced soldiers got scared, and so the “Great Skedaddle” began.

Soldiers limped, ran and drove stolen ambulances back to Washington, tails between their legs.

It wasn’t just a defeat. It was a humiliation. But what really made Emma angry was seeing soldiers run away from their duty.

“Many that day who turned their backs upon the enemy and sought refuge in the woods some two miles distant, were found torn to pieces by shell, or mangled by cannon ball. A proper reward for those who, insensible to shame, duty for patriotism, desert their cause and comrades in the trying hour of battle, and skulk away cringing under the fear of death.”

Emma didn’t run. She fell back for supplies in Centreville, then made her way to a stone church where the wounded were being kept. She was horrified to see bodies and amputated limbs piled up high, dying men with no water. She stayed with them as long as she could, hearing last words and confessions and, having no scissors, ripped away blood-soaked clothes from wounds with her teeth. In the end, she had to leave them behind and hide in the bushes to keep from being captured. It made a shame burn in her that she wouldn’t soon forget.

By the time she stumbled back to Washington, Emma was feeling disillusioned. First, because of all the death and dying. The sick tents were in chaos; dysentery and typhoid were rampant; the wards were loud, disorganized, dirty. “Oh, what an amount of suffering I am called to witness every hour and every moment,” she said. But she also discovered the same phenomena as many Civil War nurses: that after a while, the horror faded away. “There is no cessation, and yet it is strange that the sight of all this suffering and death does not affect me more. I am simply eyes, ears, hands and feet.” More than that, she wasn’t feeling good about the army’s moral fiber. “Every bar-room and groggery seemed filled to overflowing with officers and men,” she said. “...and military discipline was nearly, or quiet, forgotten for a time in the army of the Potomac.”

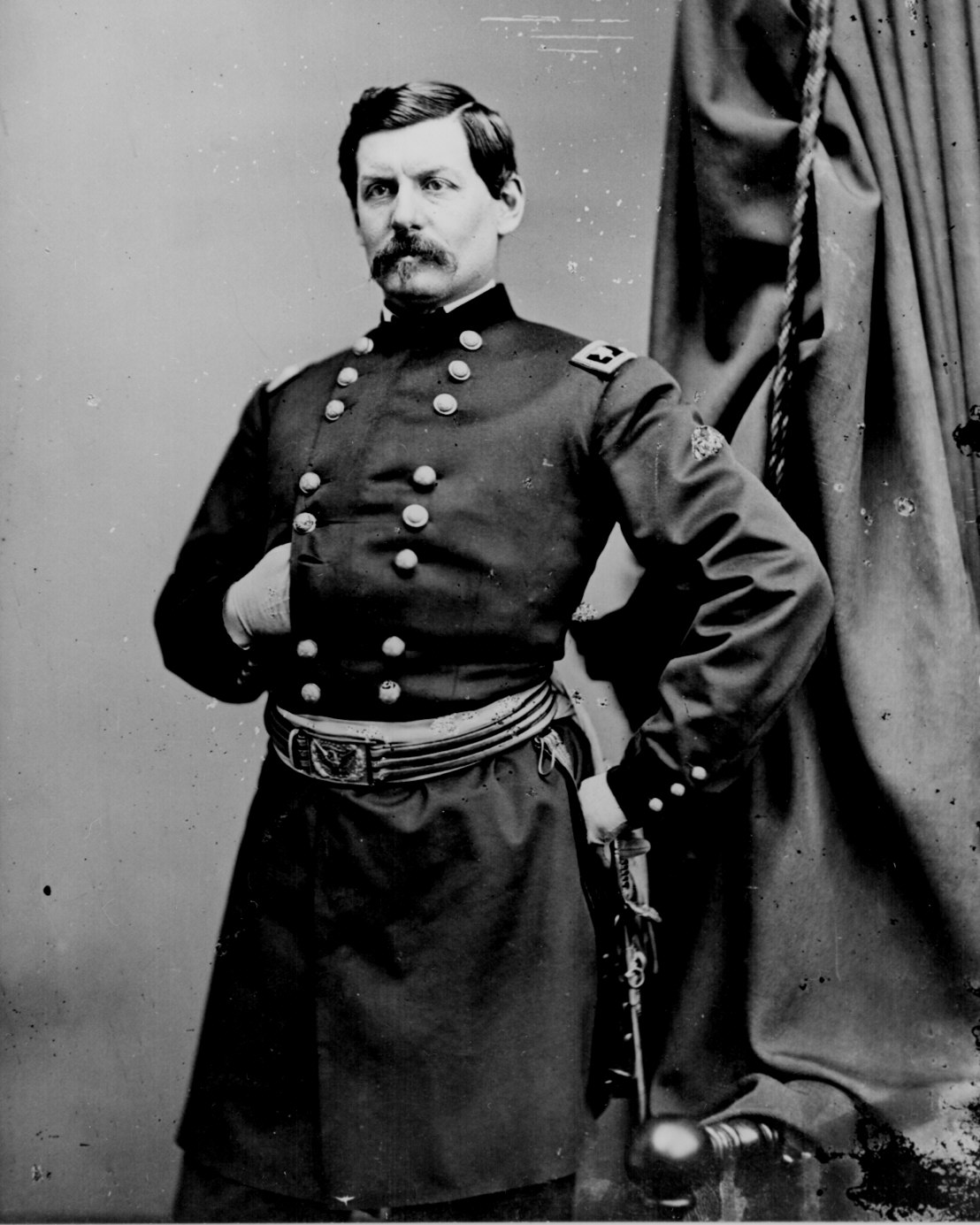

It was during this time that Emma made a friend--a rather studly friend. Private Jerome Robbins was also part of the 2nd Michigan Infantry, though a different company than hers. When they met he was visiting a wounded friend where Emma was working, and they struck up a conversation that lingered on. They found they had much in common: they both loved learning and debating, God and General McClellan, and hated the immoral way so many of the soldiers in camp acted. Their friendship was fast and deep. They could talk easily for hours, like they’d known each other for years.

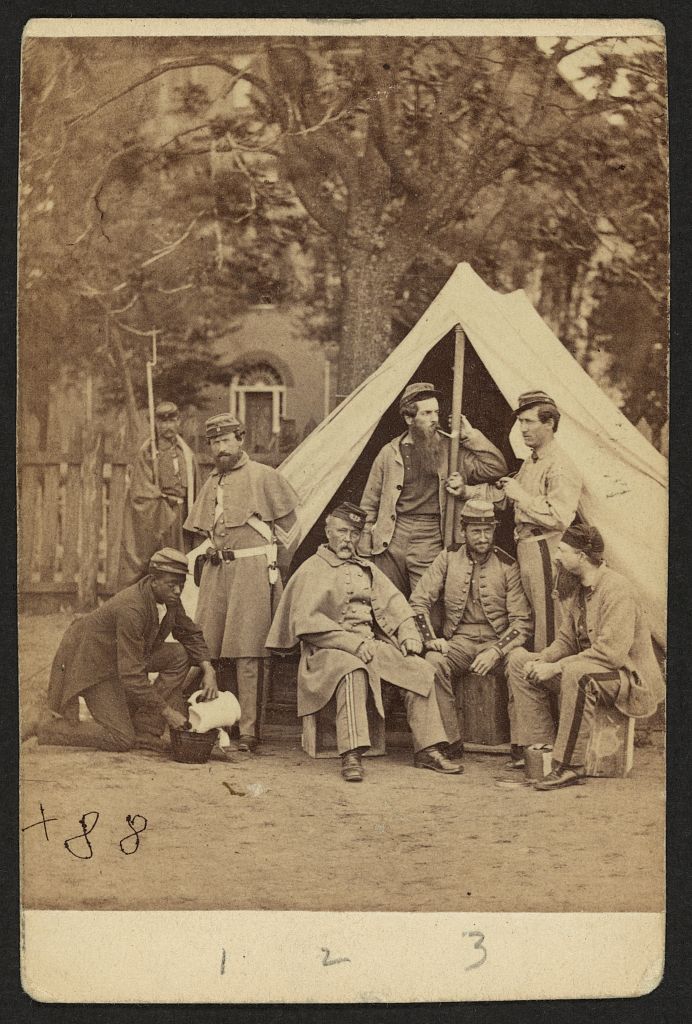

Hello there, handsome. Jerome Robbins, Emma's good friend, and maybe lover. Okay, probably NOT her lover, but they sure did like taking naps together. They met at Mansion House Hospital in Alexandria and bonded over things like General McClellan and their love of Jesus. When Emma told Jerome that she was really a lady, things got...a little bit tense and uncomfortable. But he kept her secret for the rest of the war.

Courtesy of the University of Michigan Bentley Historical Library.

Emma had long ago sworn off men - they were the source of so many of her troubles and anxieties - but there was something about Jerome. Apparently, he was taken with her as well. He wrote in his diary about having pleasing conversations with Frank Thompson, of being impressed by his nursing skills. “He is an assistant in the hospital and I think well able to win and repair the hearts of those about him,” he wrote. But he knew that there was something about Frank that he wasn’t quite getting. “A mystery seems to be connected with him. Hard to name.”

Jerome made frequent visits - sometimes multiple times a day - to the hospital. By November, Jerome became a steward there. They were joined at the hip: going to prayer meetings in the evenings, talking for hours, taking long walks together. Before long, they were even taking joint naps.

“I arose greatly refreshed after a good sound sleep on a couch with my friend Frank Thompson. ”

Amidst the chaos and the violence, he became a safe harbor. Emma longed to tell this kindred spirit who she really was, but was afraid to: what if he rejected her? What if he turned away, disgusted, never to return? There was another complication, too: Jerome had a girlfriend back home named Anna. He talked quite openly about his love for her, while Emma simmered with awkward feelings of jealousy. But there was something between them: something real. She could feel it. Emma couldn’t lie to him anymore.

One day they walked together out onto Long Bridge together. Her heart must have been pounding as she told him everything: about her family, her father, her run away from home. She couldn’t have known it, but other secret soldier girls would go on to profess their love to friends in the army, to find that love returned. And then others who, when they discovered a woman amongst them, tattled and got them kicked out of the army. This meeting could either answer her hopes or end in tragedy. It probably won’t shock you to know this little interview didn’t go quite the way she hoped.

“My friend Frank is a female,” he wrote in his diary. “I won’t say that it is not strange to me...How sad is the reaction which often occurs when we think we have friendship in exchange for friendship and find that friend differing so widely from our own natures…I learned that in friends we may be deceived”

His wrote for several pages, his handwriting gone frantic and cramped. He underlined several words, among them: heart, her, feelings, real. The entry makes it clear that it was a heated exchange, and that they both left upset and angry. “Perhaps a knowledge on her part that there is one in a Michigan home that I do regard with especial affection,” he wrote, “creates her disagreeable manner.”

The days went by, and Jerome didn’t turn Emma in. From then on, he only wrote about her as Frank. It was dangerous knowledge to have: men had been court martialed for helping women disguise their sex. But he knew it was dangerous for her, too, and kept her secret. It’s clear he felt confused about his feelings. He writes about missing Frank and wanting to talk to him; wishing that things between them weren’t so strained. But Emma didn’t know that: she was mortified, and probably heartbroken. She kept busy with nursing at another hospital and tried to avoid him at all costs.

In 1862, as the army mobilized, she came under the command of a Colonel Orlando Poe. Poe gave her a new duty: that of mail carrier. She got this job, Poe said later, because she was effeminate, and he didn’t want to take any strong-looking soldiers from the fighting ranks. But it was an important job. The only way to spread the word was by letter or by telegraph, which most soldiers wouldn’t have had access to; important information was carried in the mail. And Emma knew that “It was nothing short of a calamity for a heavy mail to be captured by the enemy.” It was also dangerous: mail carriers were often overtaken by the enemy and shot. But being so good at riding, she excelled at it. She even named her horse: Frank, of course.

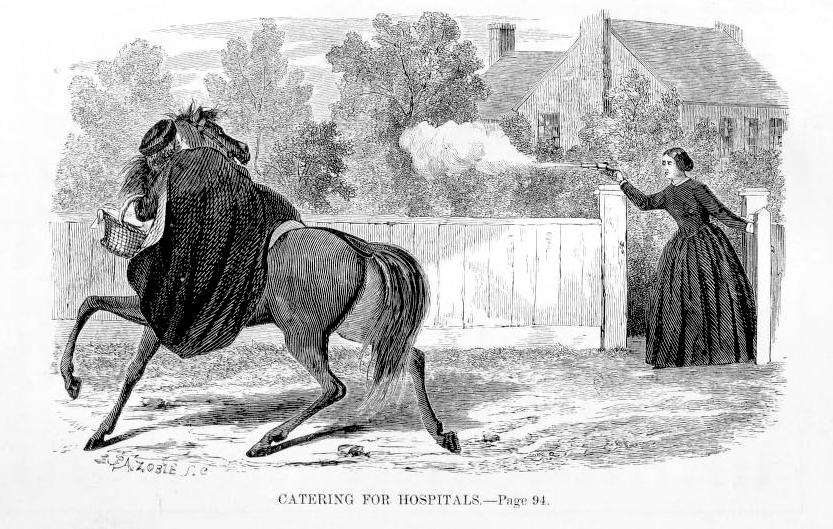

The army made their way by steamer boat, and marching through mud, down to the Virginia Peninsula. Emma would ride Frank out to neighboring farms and houses, trying to produce food for the army’s ever-dwindling supply. It was in this way that she met with a bit of a misadventure.

At one house, a woman came to the door and invited her in, rather cordially given the circumstances. As she meandered around the house, supposedly gathering supplies, Emma knew that something was off. “I looked at her; she was trembling violently, and was as pale as death.” But the woman gave her some supplies, and Emma got on her horse. It was at this point the woman shot her. Well, she missed - but barely. Emma didn’t think; she just reacted. She got out her pistol and shot the woman through her palm. The woman, shrieking, tried to run, but Emma tied her hands and led her back to camp. She did feel bad, though, so she let the woman sit on Frank for a while. But still, she told her in no uncertain terms that “if she uttered another word or screamed she was a dead woman.” Apparently, Emma’s captive ended up becoming a nurse for the Union army. They called her Nellie, and she and Emma worked side by side for a while. Bizarre.

Around the same time, Emma struck up an acquaintance with a chaplain called James. She’d known him back in Canada, but her disguise was good: he didn’t recognize her. Though it was pretty awkward to hear him wax poetical about his old friend Emma.

It’s hard to say if this story is true or not, in terms of whether he recognized her; it’s also hard to say what kind of relationship they really had. Emma does tell us in her memoir that he wasn’t married, and that there was a strong bond of sympathy between them. I like to think he might have shared the burden of her secret.

One day, Emma came back to camp to find it quiet and solemn. When she asked what had happened, they said that James was dead. “My friend!” she wrote. “They had buried him and I had not seen him!...he was gone and I was left alone with a deeper sorrow in my heart than I had ever known before.” In her memoir, there are few times we hear Emma thirst for vengeance or violence: this is one of them. The rage she felt at seeing her good friend buried made her understand why Nellie had shot her. To Nellie, Emma was a symbol of everything that had been taken away from her. Maybe that’s why she decided to accept an invitation to become a Union spy.

Meanwhile, the Union’s head detective Allan Pinkerton needed help with his spying network. The army was in desperate need of intel, and one of his best men had recently been captured. He needed to find some new recruits who could lie, pretend, be patient, cunning and discreet. It was a dangerous job - men had been hanged for it - but she was willing to go off and do something more than tend to the sick. “The subject of life and death was not weighted in the balance. I left that in the hands of my Creator, feeling assured that I was just as safe in passing the picket lines of the enemy, if it was good will that I should go there, as I would be in the Federal camp. And if not, his will be done.” And so she went back to Washington for an examination.

She was grilled by none other than General McClellan with questions about her loyalty, her allegiance. Why did she want to sign up for such a dangerous job? She passed that test, and then the firearms test, with flying colors. But she was nervous about the medical exam. What if they asked her to strip down? What would she do then? But it was just a phrenological exam - the practice of feeling one’s head and reading its lumps - which apparently proved her organs of secretiveness and combativeness were satisfactorily large. She was all good: and now officially a spy.

She only had three days to prepare for her first mission: to steal her way into Yorktown, VA. But how would she do it? Well, she decided, she’d disguise herself as a black man. Naturally.

Don't mind me...I'm just another guy looking for work in a Confederate camp! Or am I Sarah Emma Edmonds, skin died dark with solvate nitrate? Hard to say, really.

From Emma's memoir, Nurse and Spy in the

Union Army.

This sounds insane: this woman dressing up as a black man and just walking right over into the enemy camp. But apparently, it was a popular disguise. Spying was still in infant stages in America. Men dressed as women, white people pretended to be black - and it worked, maybe because people weren’t really savvy to spies yet. One thing that would have attracted Emma to the disguise is that, if caught by fellow contrabands, they were very unlikely to report you. They’d even aid you; you were, after all, on their side.

So she “purchased a contraband suit of clothing, real plantation style, and then I went to a barber and had my hair sheared close to my head.” Next, she got the postmaster to get her a wool wig from Washington and actually used it to dye her skin: head, face, neck, hands, arms with some silver nitrate. The transformation was complete. No one in her own camp recognized her. She became Ned the black man, looking for work.

She slipped out at night, past the pickets on guard duty, and spent the night hunkered down in the trees. From there, she attached herself to a group of contrabands and worked her way with them into a Confederate camp, looking for work. Without much ceremony, she found herself working on a breastwork with about a hundred others, wielding a pickaxe, shovel and wheelbarrow. By the end of the day, her hands were blistered raw. Afraid it would wear away the dye on her skin, so she got another guy to switch duties with her. She was now a water carrier, which let her roam freely around the camp and listen in. That’s what she did for two days, taking notes that she kept hidden away in her boot heel.

At some point, one of her fellow contrabands noted, “Jim, I’ll be darned if that feller aint turnin’ white.” When she looked down at her hands, she saw she WAS turning white. What to say to them? “Well, gem’in [gentlemen], I’se allers ‘spected to come white some time; my mudder’s a white woman.” And they all laughed.

She had what she needed, now: but how to get out? Later that night, as she carried dinner out to the pickets, a sergeant stopped her. A man had just been shot at his post and they needed a replacement double quick. He put a musket in her hands and said, “Now, you black rascal, if you sleep on your post I’ll shoot you like a dog.”

She was so close to the Federal line: all she could do was wait until no one was looking and make a break for it. As rain started coming down, washing over her skin, her disguise melting away in earnest, she snuck away into the night with her gun. Scared to approach the Union lines for fear of being shot, she slept in the undergrowth until daylight. In the morning, tired and silver nitrate streaked, she convinced the Federal pickets to let her back into home base.

She changed into her camp and, blistered and maroon-colored, went to report her intelligence. And how did she feel about sleeping in the woods and narrowly escaping death?

“I am naturally fond of adventure, a little ambitious, and a good deal romantic, and this together with my devotion to the Federal cause…made me forget the unpleasant items and not only endure, but really enjoy, the privations connected with my perilous conditions.”

During her time in the army, Emma would go on several more spying missions, dressed as everything from an Irish peddler woman with a dubious accent to a Southern male civilian. Though she often paid a price for going off grid without backup: once, she got lost in the swamps around the Chickahominy River, contracted malaria, and was so weak she lay there alone, without food or proper shelter, for days. It was, without question, one of her very roughest nights, and one whose consequences would follow her. “There I was, all alone, surrounded by worse, yes, infinitely worse, than wild beasts - by bloodthirsty savages--who considered death far too good for those who were in the employment of the United States Government.”

Despite the hardships, she was a successful spy, using male and female guises to sneak right into the enemy’s camp. She had too many adventures to detail them all, so I’m going to give you my favorite - and the one that officially ended her spying career.

She was dressed up as a southern civilian boy, going door to door to find eggs and butter for the army. Really, she was trying to root out Confederate plans and guerilla cells.

At one house, she found herself crashing a wedding. The bride was a widow whose husband had been killed a few months back; I mean, when pickings are growing increasingly slim, you snap up whoever you can! The groom in question was a confederate captain: tall, handsome...and a little too keen for Emma to join up with him.

“See here, my lad,” he told her. “I think the best thing you can do is enlist and join a company which is just forming here in the village and will leave in the morning. We are giving a bounty to all who freely enlist, and are conscripting those who refuse. Which do you propose to do?”

He gave her two hours to make her decision, then placed her under guard so she couldn’t run away. Thankfully, those guards were already pretty far into their cups and more than happy to answer Emma’s questions about the army’s numbers and movements.

Off they rode in the morning, probably all a little hung over, Emma as their unwilling conscript. The handsome captain told her how grateful he’d be when all this was over. The more he talked, the more anxious Emma grew. She needed to get away ASAP.

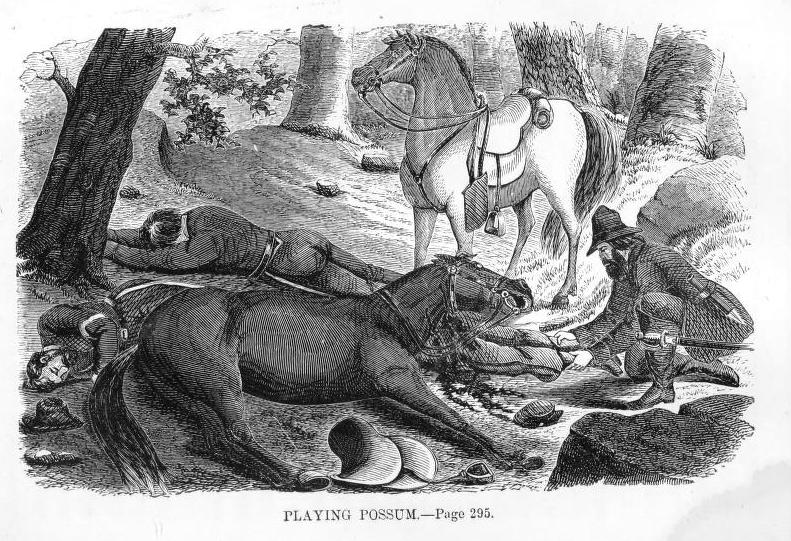

Luckily, they ran into a Union cavalry unit. There was a tussle - a confusion of guns firing, people yelling - and in the confusion, the Union captain, who recognized her, waved her over to their side. The Confederate bridegroom was not best pleased to have been duped by Emma. He stared at her in abject horror - and in that moment, they both raised their guns.

But Emma was the quicker draw. And she shot him directly in the face. Damn, Emma: you couldn’t have gone for an arm or something? The bullet punched a hole through his nose, leaving him decidedly less pretty than he’d been. “I was sorry,” she wrote later. “For the graceful curve of his mustache was sadly spoiled.” I’m not sure his facial hair situation would have been my main concern. But the 19th-century mustache was NOT to be trifled with.

When she wasn’t spying, she was mail carrying, or nursing at the battlefields. At one point, Emma was thrown off of a mule, who slipped in the mud, dumped her into a ditch, and then rolled over her. Everything hurt: her leg, a finger, a foot. When she got back to camp, she knew her leg was broken. But she wouldn’t go to the doctor for fear she’d be discovered; a visit to the hospital was the downfall of many a lady soldier. Instead, she “silently endured the misery and the distress which the unfortunate accident entailed upon me, rather than to be sent away from the army UNDER GUARD like a criminal.” To her, that was the more unspeakable horror. So she endured it.

During the Battle of Gaines Mill in May 1862, as the army retreated, Emma found herself riding to the nearby hospitals to try and help evacuate staff and patients before the Confederates could take them prisoner. It was at one of these that she found Jerome Robbins. She urged him to leave with her, but he wouldn’t abandon his patients. She must have begged him to come - the cannons were coming. If he were taken prisoner, who knew if he’d live through it. But eventually she had to leave him, not knowing if she’d see him again.

He was sent to Camp Parole in Annapolis, where he was treated fairly well, lucky for him. They wrote letters back and forth - some 11 of them from her and 8 from him between September and October. That’s more letters than he wrote his girlfriend. Just saying.

While he was away, the army marched to just outside of Fredericksburg, VA, and Emma found herself carrying mail between there and Washington. It was probably there she met the extremely tall, extremely Scottish, extremely dapper, 26-year-old Lieutenant James Reid. There’s a lot we don’t know about Reid, but what we do know is sexy. He’d joined the army with the 79th New York Militia, called the Highlanders, who showed up in Washington wearing proper tartan kilts (and one assumes no underwear). Steamy. He’d eventually been captured and taken to Richmond, but released soon after on prisoner exchange. He was very unlike her friend Jerome: tall, fair haired and blue eyed, loud and dashing…and married. But he impressed her nonetheless.

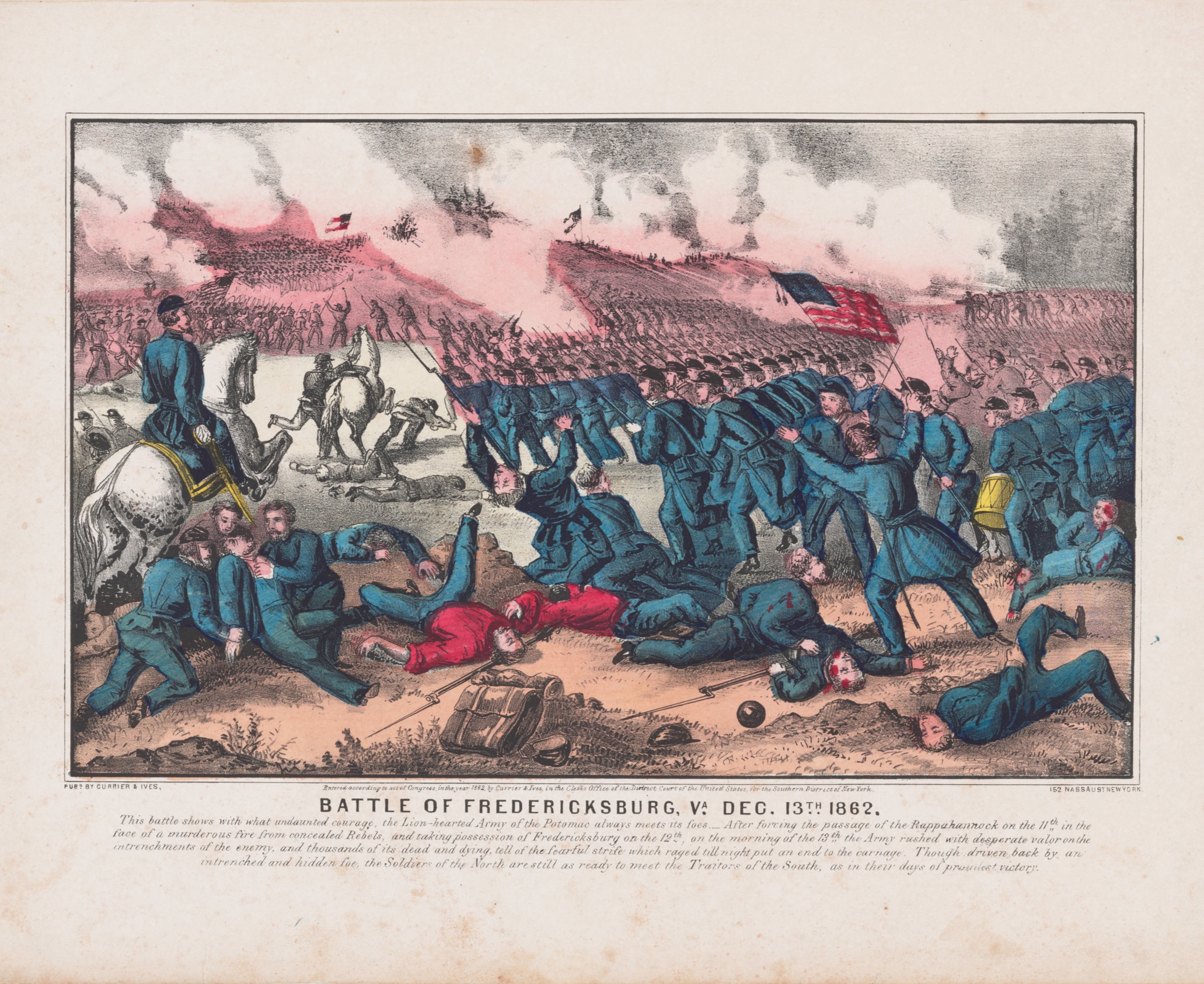

When she arrived back at camp, she found the army unhappily sitting in snow and mud, waiting. The army was either going into their winter quarters or taking Fredericksburg from the Confederates. Burnside’s staff told him it was a bad idea, but off capturing the army went.

After days of heavy fighting, Emma learned that Colonel Poe had lost his aide-de-camp. She volunteered to step in, wearing full military regalia. This was a big deal, in terms of rank and position: an aide-de-camp is kind of fancy. She rushed up and down the lines with him, carrying messages and dodging bullets. A fellow soldier said that she went “with a fearlessness that attracted the attention and secured the commendation of field and general officers.” But she also saw many awful things that seared themselves into her memory. She saw a man commit suicide on the field, and another shoot his own leg so he could get out of fighting. It was horrible to watch thousands of soldiers rush the city only to fall in rows. 3,000 soldiers were lost in the first hour alone.

And there, in the field, she saw a face she knew, lying in pain. We’re not sure if it was James Reid, the fiery Scotsman, but it might have been. She pulled him off the field, giving him opium and whiskey. And soon, he was riding back off into the field, leaving her to watch longingly - lustily? - after him.

Meanwhile, Jerome was finally being released from Camp Parole in December and making his way back to his army. He looked around the camp for Emma, but couldn’t find her. When he did, they had a jolly reunion. Good friends and close confidantes. Who knows: maybe they could be bunkmates! No, wait...Emma already had one. And he was tall, good looking, and Scottish.

Awkward!

We don’t know what their relationship was, but we know it was...close. Quite close, according to her old flame Jerome. He must not have been pleased, because he wrote in his journal with some heat about this new arrangement. “Have not had a very long chat with Frank and I feel quite lonely without him. But I suppose he enjoys his tent mate...Reid seems a fine fellow and is very fond of Frank.” Being tucked in for the winter, the soldiers didn’t have a lot to do other than hang out and perhaps stew about each other. Emma was a Christian woman: he must have thought it was all above board, or else he wouldn’t have kept hanging out with them. But still, as the months went by, he wondered what they talked about in that tent of theirs. What they shared over the long, cold nights. When they hung out, he made sure to mention his sweetheart Anne whenever possible.

He must have done that quite a lot, and things with Anna must have been progressing nicely, Because while away collecting mail, Emma sent Jerome a letter. Not one from Frank, but signed, for the first time, with her real name. And it’s...pretty telling.

January 16, 1863

Dear Jerome,

In the first place, I will say that I am happy to know that you are prospering so well in matters of the heart. In spite of the ridicule which sentiment meets with everywhere, I am free to state that upon the success of our love schemes depends very much of our happiness in this world….Dear Jerome, I am in earnest in my congratulations and daily realize that had I met you some years ago I might have been much happier now. But Providence has ordered it otherwise and I must be content. I would not change now if I could--if my life’s happiness depended on it. I do not love you less because you love another, but rather more, for your nobleness of character displayed in your love for her--God make her worthy of so good a husband.

Your loving friend,

Emma

Whew. Steamy!

In talking about this potential love triangle, I don’t mean to trivialize Emma’s accomplishments, or even to imply that she was having a wild time in camp. Though frankly, I hope she was: she deserved to have some fun and companionship between her bouts of malaria and shooting off mustaches! But I find their presence in her story fascinating. We already know that Jerome knew her secret, and that he had complicated feelings about it - and, I imagine, about developing such a close friendship with a woman, which probably completely defied many of his notions about the fairer sex. But it also makes me wonder whether or not James Reid knew her true identity, and what he did about it. Did he become a confidant for Emma - someone to be herself with as she grew increasingly lonely and weary of a soldier’s life? Or had she gotten so good at playing Frank that James never knew, even in such close confines?

During these idle months, a story spread like wildfire: a Union soldier had given birth in the field! Emma must have listened to the gossip keenly. The rank and file soldiers weren’t mad: they admired the woman. Although there was much gossip about who the father was; her tent mate, probably. If Emma was doing anything steamy in hers, that might have given her pause.

Meanwhile, Emma had grown tired of muddy marches and the army’s rotating carousel of commanders. “The weather department is in perfect keeping with the War Department, the policy being to make as many changes as possible, and every one worse than the last.”

And things around her were changing. Orlando Poe, her boss and mentor, had his commission ending. And James Reid resigned to take his sick wife back to Scotland. Many of the friends she’d made early on in her three years of service were done serving.

Plus, the malaria from her time in the swamps had come back calling. She lay in her tent all day, suffering fevers, cramps, and hallucinations. Her emotional scars were also catching up with her. One day a shell explored in camp and it turned her, as she put it, into a “poor, cowardly, nervous, whining woman.” She missed her family; she missed home; she was just... tired. “I think I realized in those hours of feverish restlessness and pain, the heart yearning for the touch of a mother’s cool hand upon my brow, which I had so often heard the poor sick and wounded soldiers speak of.” She lay in her tent, crying all the tears she’d held in for so long.

Through it all, Jerome nursed her. By night, he wrote entries that seem both worried and jealous, peeved that his good friend had given her friendship to someone else. “How strange are some of the incidents of life...It is unpleasant to awaken to the conviction that one dear as a friend can forget, in their selfish interest, that others may not be void of the finer sensibilities of the human heart. It is a sad reality to which we awaken when we learn that others are receiving the devotion of one from whom we only claim friendship’s attention.”

Emma tried to get a medical furlough, but was knocked back. So there was only one option left: to desert. Around April 17, 1863, Franklin Thompson vanished from the army. Deserting was a dangerous proposition - you could be hung for doing such a thing - and, in most people’s eyes, very shameful. But Emma didn’t think of it that way. “I never for a moment considered myself a deserter,” she said. “I left because I could hold out no longer.”

But it seems she left a bit of a mess behind her. Before James Reid left the army, just a few days after Emma did, he paid a little visit to Jerome’s tent. They had some words. We don't know what they were, but let’s pretend they went something like this:

James Reid: *sigh* I miss Emma. In my bed.

Jerome: Take that back, you horrid Scottish specimen!

James: Och, don’t be jealous just because she liked my kilt.

At any rate, Jerome was angry. He’d been her friend; nursed her; kept her secret and told her all of his. “Frank has deserted for which I do not blame him...yet he did not prepare me for his ingratitude and utter disregard for the finer sensibilities of others.” Of all others whom I trusted as friends he was the last I deemed capable of the petty baseness which was betrayed by his friend R.” I think Jerome is being a bit precious, to be honest. But he did have really excellent hair.

At any rate, the secret was out, and some people were talking. “We have been having quite a time at the expense of our brigade postmaster,” soldier William Boston wrote. “He turns out to be a girl, and has deserted when his lover, Inspector Read, and General Poe, resigned. She went by the name of Frank and was a pretty girl.”

Meanwhile, Emma made her way to Oberlin, Ohio, to recover from her illness, still living as a man. While there, she had some choices to make. Stay living as Frank, or put on a dress and be Emma again?

After traveling back to Washington, Emma wrote Jerome a letter. She wouldn’t say where she was staying, as she didn’t want the army to find her, but she did say that she heard him and James had a convo about her: care to share? It also requested he send a picture of himself. “Oh Jerome, I do miss you so much,” she said. “There is no person living whose presence would be so agreeable to me this afternoon as yours.” She said she hoped that Anna had accepted his proposal of marriage.

Well, she hadn’t: instead, she’d dumped him for someone else. This is your moment, Jerome!...cue romantic music! ...But he didn’t go to Emma. Maybe he really only felt friendship for her. Maybe he couldn’t get over what she’d done. Either way, there’s no evidence that she ever saw him again.

Emma packed her pants away and left Frank behind her. In terms of her outfits, anyway: in 1864, she re-lived all of his adventures in her memoir, Nurse and Spy in the Union Army. She used her own name - Emma Edmonds - but neglected to name her male alias. After all, Frank Thompson had deserted the army, and the war was still going on. She made up regiment and officer names, too, or just gave them initials, to keep everyone fairly anonymous. It’s for that reason that so much of what she writes, and who she’s writing about, is hard to pin down. Later, she freely admitted that her book was part fact, part embellishment, drawn from other people’s experiences as well as her own. But the underlying story checks out, and there’s no reason to doubt Emma - adventures with silver nitrate and all.

The book was an overnight success. Turns out people were thrilled to read about a secret lady soldier! Unlike our friend Loreta Velazquez from last episode, who wrote in her memoir about her many romantic conquests and generally gave no damns, Emma’s memoir stuck closely to the narrative arc of adventure books of the era. While she didn’t join for a man like Fanny Campbell: Pirate Captain, she sticks to the Female Warrior Bold motif by underlining her patriotism. And disappointingly, the book gives not even one whiff of Scottish romance. Maybe because she thought that was what an adventure story featuring a female protagonist HAD to sound like. Maybe she was just very conscious that her wearing pants and going off to war was already going to ruffle feathers, and didn’t want to get too many panties in a twist. Either way, she was careful to paint her adventures in a clean, chaste, patriotic light - and as her publisher wrote in the book’s foreword: “…perhaps she should have the privilege of choosing her herself whatever may be the surest protection from insult and inconvenience in her blessed, self-sacrificing work.”

The book sold some 175,000 copies - Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the biggest, most explosive bestseller of the 19th century, sold 300,000. So that’ll tell you something about how many people had Emma’s story in their hot little hands. And what does she do with her newfound riches - grab Jerome and a bikini and head down to Key West? Nope. She donates ALL of the proceeds directly to the Christian Commission and the Sanitary Commission to help wounded and veteran soldiers. Imagine handing over that much money, a rare windfall for a woman of her time and situation, to a cause you’ve already given so much to. It tells you more about Emma than her book ever could.

That year, she joined up with the army again: this time as female nurse, which is how she served out the rest of the war. After that, she went home to visit her family. Her parents had both passed away, but she was able to see her sisters and roam the woods with her brother. But she grew restless. On the way back to Ohio to finish the college classes she’d started there, she found Linus Seeley, a fellow Canadian she’d met during her time nursing in Harper’s Ferry. He accepted her for who she was, completely - even everything she’d done during the war.

He followed her to Ohio and they tied the knot in 1867. By all accounts it was a happy marriage. But what must it have felt like, to go from spy and free-wheeling soldier to devoted, domestic wife?

She wrote later:

“Well, you know how the census takers sum up all our employments with the too easily written words ‘married woman’. That is what I became; and of course that tells the entire story.”

And Emma was content to leave her story at that. At a time when many women were touring the country, giving dramatic reenactments of their time spying and fighting, she stayed quiet. While she was proud of her nursing, she seemed uncomfortable with all of the spying: the lying, the scheming. It didn’t fit with her new life. So she did what many women soldiers did: left it behind.

She and Linus had two boys, both of which died young, and a girl, Alice. By age 32, Emma’s health wasn’t great, in large part because of the malaria and injuries she’d suffered as a soldier. But she persevered. The couple adopted a couple of orphans, and then they moved to Louisiana to take up management of a home full of 67 more. These years were good ones: much like our friend Clara Barton, Emma was always happiest when she was busy and giving back to others. But the muggy climate kicked up her old war wounds, and before long, she really wasn’t feeling well.

Misfortune followed. In 1880, her daughter Alice died. With that, she’d lost all three of her natural born children. She lay in a dark room for days on end, grieving for Alice.

They moved to Fort Scott, Kansas, for a fresh start. Many war veterans were living there, many with health complaints from their time in the war, and before long Emma realized they were all getting pensions. That sounded nice, and fair; she thought she should be getting one, too. It was a gutsy move for a woman to go for a soldier’s pension: especially when the government didn’t want to admit women were there at all.

And so began the uphill battle to prove that she, Emma, had been a soldier in the Union Army. There were a couple of hurdles to jump: first, she had to prove that she was, in fact, Frank Thompson. Second, she had to get the desertion charge scrubbed. And of course, because she was a woman, she ALSO had to prove that her motives and behavior had been chaste and pure and clean as the driven snow. A male soldier could drink himself silly and go to brothels to his heart’s content, and he’d still get himself a pension for serving. But just by being there, a woman in camp sleeping next to other soldiers was probably a prostitute, or a deviant, or a spy. Or all three. And so she had to clear Frank’s name while also clearing hers….because, as my friends over at Queens podcast would say, sometimes history’s a bag of dicks.

She sent a letter to Michigan’s adjutant general, John Robertson, asking for Frank Thompson’s certificate of service and saying that she and Frank were the same. He wrote back that he’d be glad to, but she’d only used her initials in the letter: he’d need the writer’s name in full. So when Emma wrote back, she wrote freely for the first time. “My full name is Sarah Emma Evelyn Seelye. I enlisted and served as Franklin Thomson in Co “F” 2nd Michigan Volunteers.”

Now, she had to get some witness statements. In an era with no digital paper trail, no selfies, and no geotags, this was a crucial step. She didn’t ask Jerome; she needed people who hadn’t known her secret while she served, as she worried it would look sketchy - and potentially scandalous - to provide ones from men who knew about her, and said nothing. So she asked Mr. Hurlbert, the publisher friend who’d given her a job way back when, and was the one who published her book. She also went to see her old tent mate Damon Stewart. Remember that guy? She walked into his dry goods store in Flint, Michigan and asked if he could tell her where Frank Thompson was.

Damon: “Are you his mother?” he said, confused.

Emma: “No.”

Damon: “His sister, perhaps?”

Someone came up behind them, so she picked up a pencil and wrote on a scrap of paper:

Emma: “Quiet! I am Frank Thompson.”

He was so shocked and delighted that he invited her over to his house to meet his wife. He even invited a reporter along, who wrote a story all about Frank’s wonderful and faithful service. She stayed with them a week, during which time many of their old buddies came by to see her. Each one wrote her a letter in favor of her pension.

More and more of her old army buddies got in touch. They even made up a committee to help her win her pension. They invited her to a reunion of the 2nd Michigan, and though she was too sick to go, she was touched that they wanted to see her. “My brief message to the boys is this,” she wrote. “Frank’s heart beats just as warm and true as when it beat under a regulation blouse.” Later that year, Emma was invited to another reunion, where her friend Orlando Poe was excited to learn, after 20 years of wondering, what happened to his favorite mail carrier. The Michigan boys were all glad to see her: they clapped and yelled until she got up on the stage. She said, “Tears are in my eyes, but I shall never, ever forget your kindness to Frank Thompson. All I can say is that I am deeply grateful, and thank you.” Some of the wives didn’t share their enthusiasm. Because men weren’t the only ones who suspected lady soldiers of being loose characters. Oh, ladies. Don’t be jealous because you didn’t have the guts to go yourself!!

Finally, on March 28, 1884, the House of Representatives passed House Bill Number 5335, which said:

“Truth is ofttimes stranger than fiction… That Franklin Thompson and Mrs. Sarah E.E. Seelye are one and the same person is established by abundance of proof and beyond a doubt. She submits a statement . . . and also the testimony of ten credible witnesses, men of intelligence, holding places of high honor and trust, who positively swear she is the identical Franklin Thompson...”

It took a while longer, like years, for a special act of Congress to grant Frank/Emma an honorable discharge from the army, and with it her sign-up bonus and a veteran's pension of twelve dollars a month. It was a big win. But even then, Congress played up her nursing and played down her soldiering. They made sure to say the nursing work she’d down at the end of a war, while wearing a dress, “rendered much more valuable aid to the cause nearest her heart than she could possibly have done as a soldier.”

Emma and Linus went on to build a new home in 1889, though they never quite had enough money to turn it into the home for indigent veterans she dreamed of. She occasionally wore pants to work in the yard, which her neighbors wrote off as eccentric and endearing. The local kids were scared of her because they’d heard she was a spy in the war. They made up a game where they would try to get up close to her without her shooting off any of their mustaches. She invited them in for some cookies instead.

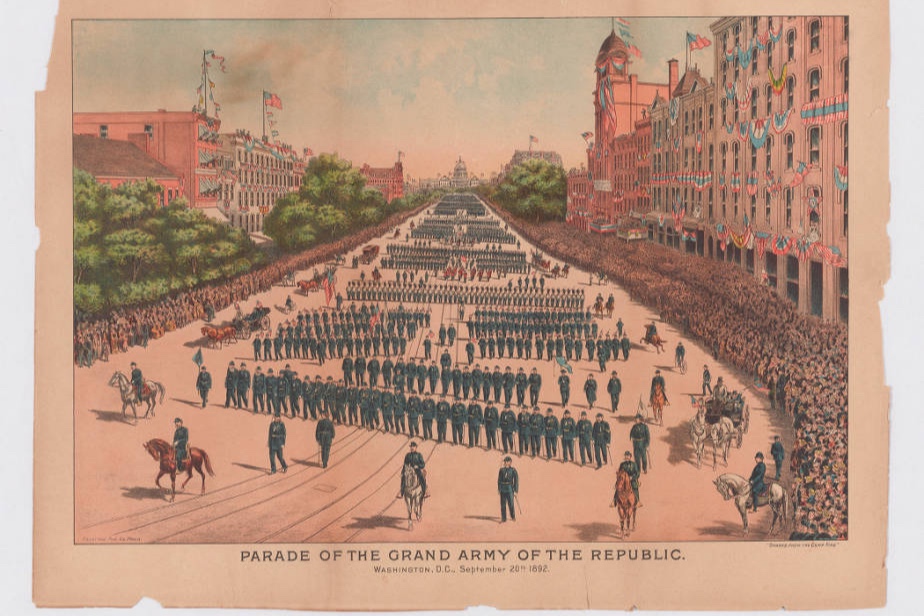

In 1897, she became a member of the Grand Army of the Republic, a nation-wide Civil War veterans group. No other woman claiming to be a soldier had been admitted, but she was voted in - the only woman ever to be so. It was, to her, the greatest possible honor. It legitimized everything she’d risked and done for the army she loved.

Emma finally died of her malaria on September 5, 1898, at the age of only 56. She was buried with full military honors in La Porte, but was later moved to Houston’s Washington Cemetery - to the Grand Army of the Republic grave site, buried with full military honors.

In his address to the Second Michigan in 1901, Colonel Frederick Schneider said: “No war ever displayed so much bravery and devotion among women as did the great Civil War. But none of the many instances recorded have surpassed the record for pure, unselfish patriotism and zeal for the cause of humanity, daring bravery and heroic fortitude as that of Sarah Emma Edmonds... the whole world made better from her having lived in it.”

Years later, in the 1920s, her obituary was found folded neatly into one of Jerome journals. It read, “A remarkable character has passed away.”

She was indeed a remarkable character.

At 17, she became Frank Thompson, braving the threat of imprisonment and social exile to make her own way in the world. She joined the war effort, even though she didn’t have to, saving lives and tending wounds, no matter what it cost. She fought for her right to get the pension she’d worked so hard for, proudly defying the notion that women were never there. Emma was never afraid to fight for what she believed in. I hope to one day be as brave.

Until next time.

Voices

Sarah Emma Edmonds = Claire Burke

Jerome Robbins = Avery Downing

James Reid = Simon Dinatris

Soldiers = Phil Chevalier, Andrew Goldman, and John Armstrong

Music

"Hoh Harph," "Speedy Delta" and "Driving to the Delta" by Lobo Loco. All other music is from Audioblocks.