That Loosener of Limbs: Sappho and Sexuality in Ancient Greece

When it comes to the words that made it through time to us, ancient Greece is particularly loud with men’s voices.

But if you listen, you hear one woman through the crowd—we still hear her today, thousands of years after she lived.

Heralded as a genius in her time, she was called “The Poetess” and “The Tenth Muse.” People made coins with her face on them, and created honorary statues of her all over Greece. Even Aristotle, that grumpy bastard, wrote she was “honored even though she was a woman.” Sappho wrote poetry that rocked her ancient world.

In our century, she’s heralded as one of the earliest same-sex love advocates, boldly writing about lesbian desire. It’s from her home island of Lesbos that we get the word “lesbian.” But when you look for the woman behind the name, she turns into one of those Victorian-era shadow portraits: no individual features, just an outline filled in with a whole lotta black.

Who was this mysterious woman poet? What did it mean, in her time, to write about same-sex relationships? And what did it mean to be in one?

Grab your lyre, a flower crown, an open mind and your fanciest pen. Let’s go traveling.

let’s get inspired,

shall we?

Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema's Sappho and Alcaeus, courtesy of The Walters Museum.

MY SOURCES

books

Ancient Greek Love Magic. Christopher A. Faraone, Harvard University Press, 2001.

Sappho: A New Translation of the Complete Works. Cambridge University Press July 2014.

The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women Across the Ancient World. Adrienne Mayor, Princeton University Press, Sept. 2014.

PODCASTS

071: “Love, Sex and Prostitution” by Ryan Stitt, The History of Ancient Greece Podcast. This episode is chock full of fascinating details about sexuality in ancient Greece.

“Sappho of Lesbos.” The Dirty Bits, Tawny Platis. I didn’t listen to this one until AFTER I was done researching mine, but it’s delightful. If you enjoy Sappho’s voice in my episode, definitely go and check out this one!

online

“Girl, Interrupted: Who Was Sappho?” By Daniel Mendelsohn, The New Yorker March 2015.

"Guide to the classics: Sappho, a poet in fragments” by Marguerite Johnson, Feb 2018, and “The myth of the ancient Greek ‘gay utopia’” by Alastair Blanshard, Dec. 2017, Theconversation.com.

“Sappho.” The Poetry Foundation.

“Four Ways to Love: How the Ancient Greeks Used Magic to Fulfil Hopes, Dreams, and Desires,” Feb 2017, and “Homosexuality in Ancient Greece - One Big Lie?” Dec. 2018, AncientOrigins.com.

“Homosexuality.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

“Acceptance through Restriction: Male Homosexuality in Ancient Athens” by Brigid Kelleher, Historical Perspectives: Santa Clara University Undergraduate Journal of History, Series IIVol 16, Article 1, 2011.

“A brief history of sex and sexuality in Ancient Greece” by Paul Chrystal, Historyextra.com, June 2016.

“Sappho of Lesbos,” “Telesilla of Argos,” “Anyte of Tegea,” and “Ten Noble and Notorious Women of Ancient Greece” by Joshua J. Mark, Ancient History Encyclopedia.

“Sappho and Her Social Context: Sense and Sensuality” by Judith P. Hallett, Signs Vol. 4, No. 3 (Spring, 1979), pp. 447-464, The University of Chicago Press.

“The Parody Of A Sex Manual That Sparked The Passions Of The Ancient World” by María Isabel Carrasco Cara Chards, CulturaColectiva.com, Sept. 2017

transcript

I CHOP AND CHANGE AS I RECORD, SO THE audio WON’T BE A PERFECT MATCH FOR THE TEXT BELOW. IT’S VERY LIKELY THERE ARE TYPOS, too - I DO MY BEST, BUT when it comes to getting an episode up something has to give, ya know? also, the quotes in bold are ones I’ve made up for the drama, so please don’t quote them in your high school history paper as fact!

HER LIFE AND TIMES

If you’re thinking this episode might be just the thing for your family road trip, be warned: we’re about to sail through some pretty racy waters that may not be suited for tiny ears.

Sappho is born somewhere around 630 BCE on the Greek island of Lesbos, not so far from modern-day Turkey, and lives most of her life in the island’s main city of Mytilene, or perhaps Eressos. She is surrounded by hot sun, sparkling blue sea, craggy fields, and a flowering culture that seems to have more room for female intellectuals. But it’s also a place full of clan rivalries and dramas. We think she’s exiled at least once to Sicily for having political views that ruffle one too many important feathers. If her poetry is anything to go by, we think she has several brothers. In Herodotus’s Histories, we get a reference to one of them: a charming sailor named Charaxus, who pays quite a huge sum to buy his favorite hetaira Rhodopis down in Egypt. Herodotus says that Sappho later writes a poem publicly rebuking Rhodopis for stealing his money, and her brother for buying himself such an expensive lady. Oooh, burn!

You’d guess that, given her career path, she must be brought up by some fairly progressive parents, but she’s probably subject to many of the same restraints as other Greek women: the pressure to focus on domestic tasks, not to mention marrying young. But from what we know, it seems like the island of Lesbos may give their ladies a bit more room to move, which probably helps, as does her family’s fairly lofty status.

Growing up, we assume she gets some lessons in music, or at the very least the chance to pursue her own study of it. It turns out she’s got quite the way with a lyre. But to become The Poetess, revered and respected as an artist, she must be some kind of force to be reckoned with.

Like with the majority of ancient women, we don’t know what she looks like. Thankfully, ancient men just LOVE rating ladies on the prettiness scale and telling us all about it, but we have a few contradicting reports. Plato says she’s beautiful. A literary papyrus from long after she lives describes her as pantelos mikra, or “quite tiny.” Another guy describes her as “very ugly, being short and swarthy.” I like what Alcæus, another famous poet from Lesbos, calls her: “Violet-crowned, pure, sweetly smiling Sappho.” What goes on behind that sweet smile we can only guess.

This is probably not what Sappho looked like. But points for trying.

Detail of Sappho from Raphael's Parnassus (1510-11), shown alongside other poets. Wikicommons.

As she gets older, we think she might run a school for girls. Emphasis on ‘we think she might.’ It may just be that she keeps a girl posse around her—women she’s tutoring, say, or a group that’s some mixture of Sappho fan club and intellectual collective. She might even get married: if her poetry can be believed, she might also have a daughter named Cleis. SO many question marks. But when it comes to her work, we know a bit more.

In ancient Greece, you have a few kinds of writing: plays, verses meant to be recited out loud, elegies, usually accompanied by a flute, and epic poems like the Iliad. And then there’s lyric poetry. The lyric poetry of Sappho’s day is not the kind you still have nightmares about, recited in the slow-droning voice of your high school English teacher. Unless I was your English teacher, in which case everything was interesting and glorious. Instead they’re crooned out as melê, or “songs,” set to a specific meter and paired with a tune on the lyre. They’re performed at public events and private dinners, either by a solo performer or a chorus. So instead of Bon Iver playing through speakers at your dinner party, you’d have a live chorus plucking at strings.

Sappho writes in several different meters, but she isn’t just copying what all the emo poet boys are doing. Instead she goes ahead and invents an entirely new kind of meter, called the Sapphic Meter, with three lines of eleven beats and a final line of five. She’s also said to invent a particular kind of lyre and the plectrum, a kind of string pick. Kind of a big deal.

Her work is wildly popular, spread across the Greek world by the musicians who learn and perform her work. A writer named Stobaeus tells us that Solon of Athens is so thrilled with one of Sappho’s compilations that he asks the musician to teach it to him. When someone asks why he says: ‘So that I may learn it, then die.’ And apparently this guy was NOT one to cry over cute Superbowl commercials, so this counts as major praise indeed. Her work is so famous that people use phrases she coins in everyday conversation, just like we use Shakespearisms today. Where Mr. William gave us catchy turns of phrase like “Mum’s the word” and “neither here nor there,” Sappho gifted the ancients with new ways of describing beauty: phrases like “love, that loosener of limbs” and “more golden than gold.”

Given how we talk about her, you’d think that Sappho is the only female poet in ancient Greece. But there are others. Antipater of Thessalonike gives us a list of Nine Grecian Female Lyric Poets. Let’s let him introduce them to us:

“These are the divinely tongued women who were reared on the hymns of Helicon and the Pierian Rock of Macedon: Praxilla, Moiro, Anyte the female Homer, Sappho the ornament of the fair-tressed Lesbian women, Erinna, renowned Telesilla, and you, Corinna, who sang of Athena’s martial shield, Nossis the maiden-throated, and Myrtis the sweet-voiced, All of them fashioners of the everlasting page. Nine Muses Great Ouranos bore, Nine likewise Gaia, to be a joy undying for mortals.”

Surprised there are so many? We shouldn’t be, considering the nine Muses the ancient philosophers all prayed to for inspiration were female.

just living that muse life.

The Nine Muses, from a Roman sarcophagus, courtesy of the Louvre

I don’t think Sappho will mind if we take a few minutes to meet a few of them.

One of the major names on Antipater’s list is “renowned” Telesilla of Argos. As a fifth-century youth, she was often quite sickly, so she prayed to the gods for guidance. They tell her that to get well, she should devote herself to the Muses. And so, much like many a 19th-century invalid who found themselves miraculously healed by spirits, she gets well as soon as, you know, she has something to do other than wait by her hearth to get married. Much like Sappho, she pioneers a new poetry meter, known as the Telesillean Metre. And though only a few of her lines have trickled down to us, she’s influential enough to be mentioned by such literary greats as Pausanius, Plutarch, Athenaeus, and others.

And in the midst of writing furiously and being rather famous, she also helps defend Argos against the Spartans in 494. After the Spartan king burnt many of her kinsman alive as they hid in a local sanctuary, she puts down her quill, says “not on my watch, and mobilized the women, kids, and elderly left behind in the city to fend the invaders right off. “With Telesilla as general,” Plutarch says, “they took up arms and made their defense by manning the walls around the city, and the enemy was amazed.” Did this for sure happen? Scholars aren’t sure, but I also like the image of a poetess picking up her spear and showing those Spartans how a battle is won.

Ladies with wings: crazy inspirational. Why shouldn’t they be inspiring ancient Greek women as well?

Hesiod and the Muse (1891), Gustave Moreau, Wikicommons.

And then there’s Anyte of Tegea, who Antipater calls “the female Homer.” We actually have more of her work in hand than we do of Sappho’s. This third-century poetess was one of the first to focus in on the natural world rather than devoting her work to the godly realm, and also one of the first to write the epigram: a pithy saying meant to be clever, amusing, and often sarcastic. Some of her most famous work was in the realm of epitaphs, which it seems many people are eager to have her write for them. Here’s a touching one about a boy who dies in battle:

The earth of Lydia holds Amyntor, Philip’s son; he gained many things in iron battle. No sickness led him to the house of night; he died, holding his round shield before his friend.

She’s especially good at memorializing pets, like in this one she wrote for someone’s beloved dog:

You died, Maira, near your many-rooted home at Locri, swiftest of noise-loving hounds; A spotted-throated viper darted his cruel venom into your light-moving limbs.

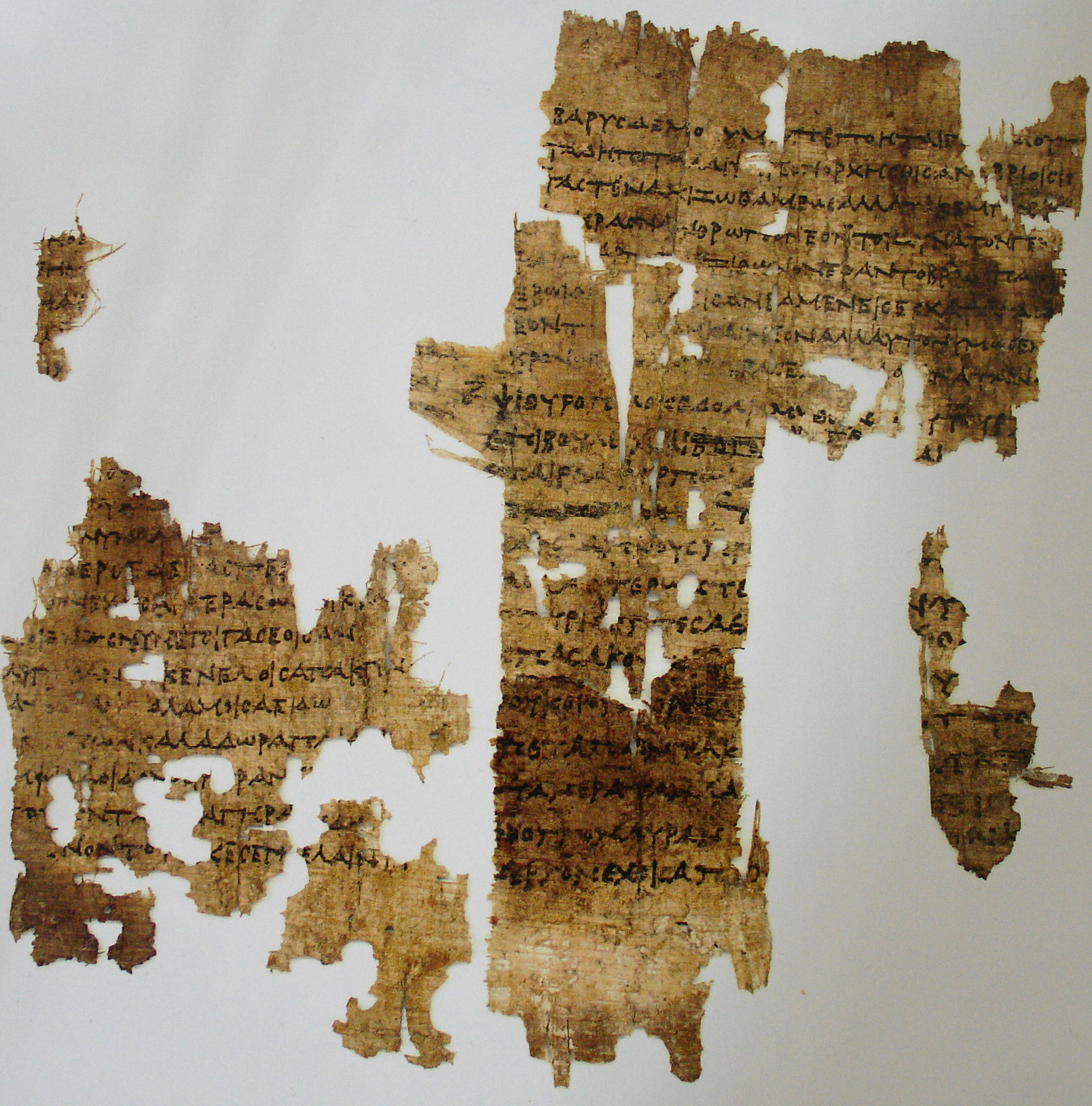

And then there’s Philaenis of Samos, who’s a very different ball of authorial wax, but whose writing is pretty poignant to this episode’s subject matter. This 4th century courtesan becomes quite famous for writing a sex manual covering everything from lesbian sex positions to the proper etiquette for courting, regardless if the object of your love is of the same sex or opposite. I wish I could quote you some of these gems, but alas, her work hasn’t made it down to us: we only know about it because of what other writers have said. We know almost nothing about her: most of our intel was found in the ancient Egyptian city of Oxyrhynchus, which means “City of the Sharp-Nosed Fish.” Sounds fragrant! She comes from the island of Samos. Given that her name is the diminutive form of philaina, the feminine term for philos, or love, we think she was probably writing under a pen name.

So given that Sappho isn’t the only lady writer around the place, what is it that the ancients are so obsessed with? And what can her work tell us about the woman she was?

Here’s a quick ex-English teacher disclaimer: we have to be careful about reading a woman’s poetry and judging it as her personal truth. Author and Narrator aren’t the same person; just because someone writes about serial killers, it doesn’t mean they are one, know what I’m saying? But the thing that makes her poetry so special is that it’s refreshingly intimate for her era; personal in a way that little ancient poetry is. It makes it tough not to insert the Poetess into her creations. Many of her poems deal with love, and the object of that love is often another woman.

In this work, which we now call “I Have Not Had One Word From Her,” translated by Daniel Mendelsohn, we see that Sappho knows what it means to wait for a text from her latest crush:

I have not had one word from her

Frankly I wish I were dead

When she left, she wept

a great deal; she said to me, ‘This parting must be

endured, Sappho. I go unwillingly.’

I said, "Go, and be happy

but remember (you know

well) whom you leave shackled by love

If you forget me, think

of our gifts to Aphrodite

and all the loveliness that we shared

all the violet tiaras,

braided rosebuds, dill and

crocus twined around your young neck

myrrh poured on your head

and on soft mats girls with

all that they most wished for beside them

while no voices chanted

choruses without ours,

no woodlot bloomed in spring without song.”

Whoo. Hurry back, anonymous girlfriend! There’s some serious romance happening here.

hello, lover.

Sappho and Erinna in a Garden at Mytilene, Simeon Solomon, 19th century. Wikicommons.

Most of her poetry has come to us in fragments: In this one, she reminds us how difficult it can be to breathe when someone beautiful walks into the room:

your beguiling laughter: O it makes my

panicked heart go fluttering in my chest,

for the moment I catch sight of you there’s no

speech left in me, but tongue gags—: all at once a faint

fever courses down beneath the skin,

eyes no longer capable of sight, a thrumming in the ears,

and sweat drips down my body, and the shakes

lay siege to me all over, and I’m greener

than grass, I’m just a little short of dying.

Most are just tantalizing snippets of her complete poems, but they give us a sense that she has a deep understanding of love and longing. Here’s another:

You came, I yearned for you,

and you cooled my senses that burned with desire

And this one:

love shook my senses

like wind crashing on mountain oaks

And then there’s this one, where we see the word “bittersweet” applied to an emotion for the first time we know of in Western lit:

Once again Love, that loosener of limbs,

bittersweet and inescapable, crawling thing,

seizes me.

So IS Sappho what we modern-day listeners would consider a lesbian? What does it mean to be gay in ancient Greece?

When we talk about ancient world homosexuality, things can get confusing for the time traveler quite quickly. Our modern labels and framework about understanding sex and gender aren’t the same ones the ancients are working with. Though the word homosexual has Latin roots – “homos” meaning “same” – the word doesn’t show up in writing until the 1880s. The word “lesbian” isn’t coined until the Victorian age. If you throw such words at the ancient Greeks, they’ll just blink at you. Even if you explain what they mean in our century, they’re unlikely to understand what you’re going on about, because they perceive sex as an act, not as an identity or orientation, and rather as a passing state of being than as a permanent way of life.

To understand same-sex love in ancient Greece, we have to try and understand how they think about love, sex, and marriage.

GETTING DOWN IN ANCIENT GREECE

First, let’s talk about love. The ancient Greeks see four different kinds. There’s agape: a selfless love, like a kind of charity, that we should aim to extend to everyone. Then storge, a kind of familial love that comes from familiarity or dependency. There’s philia, a highly connected state of love between comrades. Philia is about loyalty, deep emotion and communion. And then there’s eros: a sexual or lusty love, which is seen as both intoxicating and potentially dangerous: something that lures men away from their iron-clad control, which they must always hold onto if they want to stay men. But eros can be good in that it leads to philia, a rational and intimate form of love that’s about respect and equality: that’s the kind of love we’re shooting for. Pausanius calls it heavenly love, which tends to inspire men to “turn to the male, and delight in him who is the more valiant and intelligent nature.”

Male bodies are considered almost sacred: that’s why they spend so much time in gymnasiums getting buff. Being ripped is a way of being a good citizen, because the body is a temple—well, the man’s body, at least. So when men sexually commune with each other in certain contexts, as long as philias, that highest form of love, is involved—is something sacred, too, from which they can both grow and learn. Unlike sex with the beastly ladies. Besides, the gods do it: Zeus, that voracious lethario, is known to have taken several male lovers. And if that isn’t divine, then what is?

As Aristophanes has it in Plato’s Symposium, we were once all part of a greater whole, and when we’re born and split from that whole, we’re always looking for our other half. Sometimes that other half is the same sex we are. In this way, men who turn to other men are “valiant and manly,” because they “embrace that which is like them.”

Same-sex relations between men are easy enough to find in ancient Greek writing. To begin, they’re almost always between an adolescent boy and an older man. The tradition of pederasty, which means “boy love,” is a rite of passage that goes back to ancient Greece’s tribal beginnings. When a boy neared adulthood, he’d leave civilization and go into the woods with an older man as a rite of passage.

That man, called the erastes (lover), would guide the eromenos (beloved), serving as his mentor and his protector, showing him the ways of the world—and as a reward, gets to play some horizontal love tennis. As time goes on, they stop leaving the city to have these years-long relationships and simply have them at home. A lot of these relationships probably start at the gymnasium, where teenage boys and their older comrades alike train to become hoplites, or citizen soldiers. I mean, they do all work out in the nude together. As Theognis tells us, “Happy is the lover who works out naked and goes home to sleep all day with a beautiful boy.” In a giant room filled with ripped, exposed abs, it isn’t hard to see how such friendships are struck. I can just see them now, hovering by the bench press: “Hey, handsome. Wanna go discuss philosophy and, oh, I don’t know, maybe bone?”

But these relationships aren’t just about eros, or base desire: they’re supposed to be an expression of a deeper, nobler love. As such, the erastes is supposed to subtly woo the eromenos with gifts and noble gestures, always under the watchful eye of a trainer or guardian. Young men get flattery and flowers, and we ladies get…a marriage contract. Sexy. The youth is supposed to hold off for a while to make sure they’re after more than a bedfellow, but will act as a proper friend and mentor.

Time traveling hint: if someone offers you a rabbit or a leg of mutton, they probably are making a sultry move on you. There are much racier Greek vases with same-sex love scenes on them, but I’ll let you Google those for yourself.

A love gift: a man presents a leg of mutton to a youth with a hoop, in an allusion to pederasty. Athenian red-figure vase, ca. 460 BCE

If he agrees, the younger man gets an education and an introduction into society, politics, and the ways of manhood; his mentor might even take him to symposia and to see courtesans to learn the ways of heterosexual lovemaking. Aeschines tells us that many Athenian fathers actually hope their son grows to be good looking and cause fights between older potential erastes as it’s sure to help his fortunes and his career down the line.

It seems that within these particular confines, the ancient Greeks are just fine with same sex coupling. They understand sex as an act, not an identity, and they define relationships in terms of who is playing what role. For instance, they don’t consider two men being together as a homosexual act, because one party – the older guy – is playing the dominant “man’s role” and the younger one is playing the passive “woman’s role.” In that moment, he’s no longer considered a man. It’s a perilous position for a young Greek man to be in, as anal sex is often considered disgraceful. That’s why, if Greek vases are anything to go by, the eromenos sometimes performs a different kind of penetration: one that involves essentially rubbing his magic man stick between the boy’s thighs to get his jollies.

And it’s understood that this relationship is a passing thing—a boyhood rite of passage, not a way to live for the rest of your life. Once your beard grows in and you’re considered a man, you’ve gotta leave that older man loving behind you. Those men who choose to continue on into adulthood, or men of the same age, find themselves in a much less agreeable social position. Because grown men who turn to men their age for company not only turn their backs on their citizen duties, but turn themselves into a woman. Horrors!

Such bonds are even encouraged in the ancient Greek military. In myth, there’s the story of the mighty warrior Achilles and his best friend Patroclus, as told in the Iliad, who share a very deep emotional bond—given that Achilles completely loses his shit after Patroclus dies in battle, many have read that relationship as sexual. Sometimes all-male bands are encouraged to develop romantic relations because it makes them better fighters, more willing to fight and die for each other. As Plato puts it, “A handful of such men fighting side by side will defeat the whole world.”

The real-life Sacred Band of Thebes in the 4th century was made up of 150 pairs of gentleman lovers, considered better warriors because of the deep bonds they share. They fight well in several battles, until Philip II of Macedon gets to them. Even he’s so impressed with their bravery that he builds them a monument and says: “Perish miserably they who think that these men did or suffered aught disgraceful.”

Would you say Achilles is taking the death of his maybe-lover well? Nope. Not well at all.

Achilles Lamenting the Death of Patroclus, 1760, Gavin Hamilton, National Galleries Scotland.

Make no mistake: this is not a same-sex utopia, and the kinds of things philosophers have to say about it aren’t the same as what’s accepted in practice. There are laws that dictate what age the younger boy should be, who is allowed to pair off and how these relationships should happen. One thing’s certain: they aren’t meant to last past a certain point.

There are punishments for those who refuse to give up homosexual relations outside of society’s bounds. And not all Greek societies are down for it. In ancient Sparta, says Plutarch, affectionate regard between boys is OK, but there is to be no hugging, because that kind of affection is for the body and not the mind. Men caught embracing risk being deprived of civic rights for life. In Greek myth, Orpheus – the man who goes to the underworld to save his female lover, only to lose her – decides enough with the ladies and turns his attention to young men. That angers some female followers of the god Dionysus, chief executor of wine and drama. So they dramatically tear the guy apart, throwing his head into the Hebrus River. The lesson: even if you’re a god, you should stay in your lane.

But what about lady loving, you wonder? The truth is we don’t know much about how the ancient Greeks think about it. I mean, it’s not like women have sexual urges, say the experts, and they don’t have pointy man sticks to duel with. So…romantic love between them can’t be a thing!

While later historians will claim that all-female tribes of Amazon warrior women were lovers of the ladies, the general wisdom on sexuality in ancient Greece doesn’t back up the claim. Guys like Plutarch believe that when it comes to attraction, like calls to like. Because Amazons tend to be a bit manly, he says, they’re naturally attracted to particularly manly men. So it’s only extremely feminine women who are attracted to other women. I guess ancient dudes didn’t think that was worth writing about.

But there are other ideas. Take Aristophanes ideas in Plato’s symposium about how we’re all separated halves of a united whole always trying to find each other: that applies to men attracted to men and women attracted to men. It’s not about orientation, but connection. Plato also tells us plainly that some women “do not care for men but have female attachments.” Though he gives us no notion of what those look like in practice.

Luckily, Sappho gives us beautiful glimpses. But until someone invents a real-life time machine or discovers Sappho’s long-lost super-secret journal, we’re unlikely to ever know whom she loved.

We also don’t know how she died—hopefully peacefully and surrounded by her favorite lady lovers. It probably won’t shock you to know that men start telling tall tales about her demise pretty quickly. A Greek guy named Strabo tries telling everyone she leapt off the Leucadian cliff, a place where jilted lovers were known to throw themselves into oblivion…over some man. Mmmmk, Strabo.

I guess this guy agrees with Strabo about the whole jumping-off-a-cliff thing, looking super emo. But I’m not buying it for a second.

Sappho (1877) by Charles Mengin, Wikicommons.

Centuries after her death, Greek comedians started to work her into parodies in which she and other women from Lesbos are painted as oversexed and whorish. To them, the word “lesbian” has a whole different, and derogatory, meaning, and nothing to do with same-sex loving. Thanks to them, the Greek verb lesbiazein—which translates to “to act like someone from Lesbos”—implies the act of giving someone a blow job. Women from Lesbos are happy to sleep with whoever, these comedies suggest. Classy.

A philosopher named Seneca later complains that some guy wrote this epic manifesto about whether or not Sappho was a prostitute. The accounts of her were so widely different that some ancient writers thought there must be two Sapphos: one who wrote great poetry, and one who was a notorious sex worker. Because they can’t possibly be the same person! The Suda, a tenth-century Byzantine encyclopedia, is where we get a lot of her bio from, written centuries after Sappho’s time. They list her husband as Kerkylas, which it turns out is a combo of the Greek slang for penis and the word for man. So they’re listing her husband as, I kid you not, “Dick of Man.” Which was probably an ancient joke about her sex life. LOL?

Why was this the running joke they decided to go with? Because Sappho was too admired, and therefore threatening? Or did same-sex desire on the page feel like something they had to compensate for?

Regardless, she’s become a lesbian icon: most people know her name, which is crazy considering how little of her work we’ve discovered. Sappho wrote some 10,000 lines in her lifetime, but today we only have about 650 of them. She wrote nine books of poetry – or rather, papyrus scrolls – that once circulated widely. A copy was once kept in the Great Library of Alexandria in Egypt, one of the ancient world’s most coveted libraries. The scholars there enshrined her into their canon of nine lyric geniuses—the only woman on that list. It seemed like her work wasn’t going anywhere in a hurry. Three centuries after her death, one guy confidently exclaims: “the white columns of Sappho’s lovely song endure / and will endure, speaking out loud . . . as long as ships sail from the Nile.” Given that the great Library burned to the ground, I’m pretty sure he may have jinxed it.

And though some people posit that her poems were destroyed because they advocate lady-on-lady action, we can mostly blame the brutal ravages of time. A whole lot of her work, plus some things by Homer and Plato, were actually discovered in Egypt in a place called Oxyrhynchus. It wasn’t found in the city itself, but the site of its ancient garbage dump. The ancient world burned often; scrolls were lost or damaged; there was no printing press, no universal server. It's kind of a miracle we have any of her work at all.

The rest comes down to misunderstanding and some creative censoring. Remember that lyric poetry was meant to be memorized and recited, not passed around in written form. Plus, she wrote her work in an Aeolic Greek dialect that was hard for Homeric Greek writers to translate, and those lazy bastards were like “ugh, maybe later.”

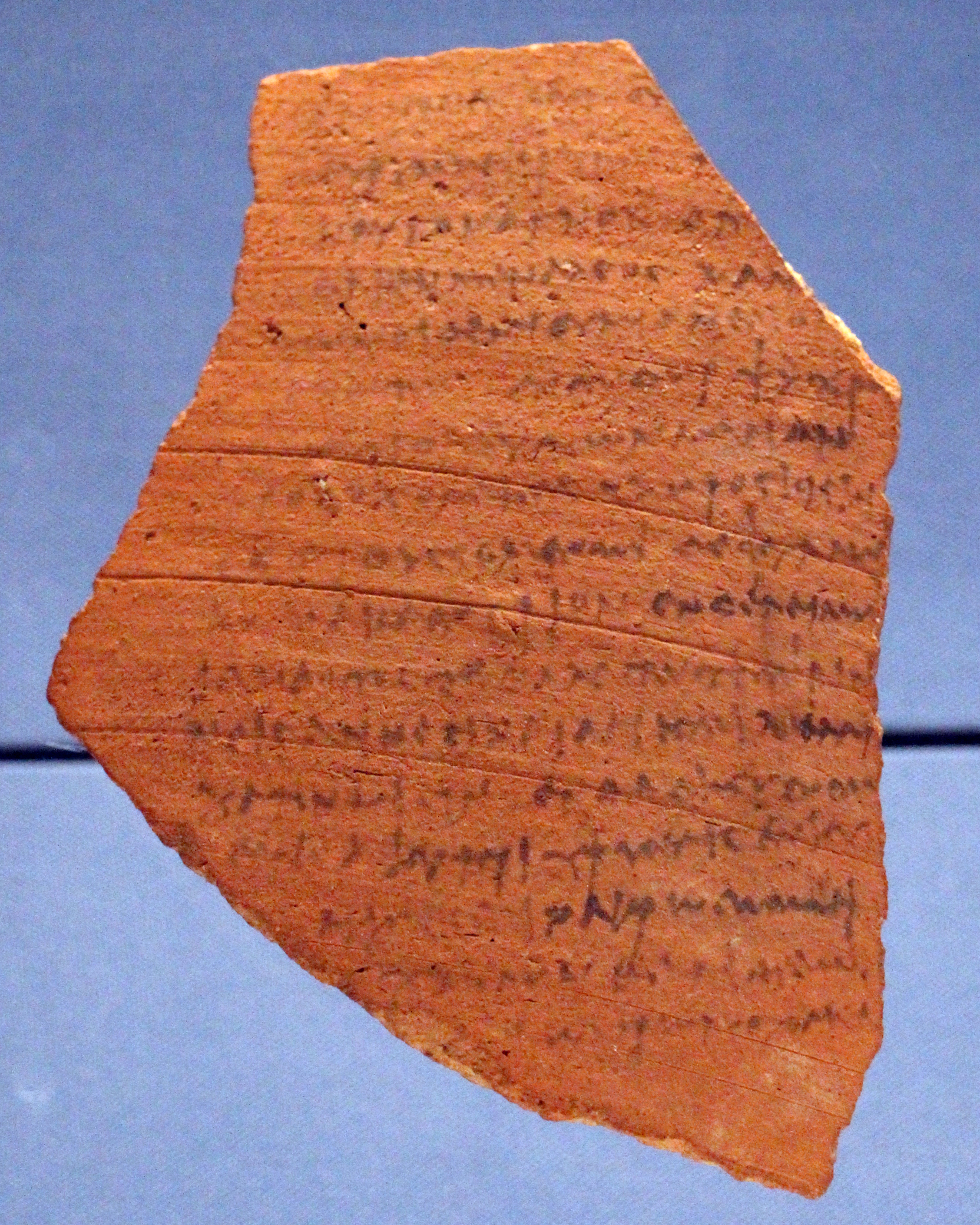

So it was all passed down in snippets, sometimes orally, probably miscopied by her fans as time went on. One piece of a poem about Aphrodite and her temple, which gives us the lovely line “where cold water ripples through apple branches, the whole place shadowed in roses,” was found scrawled on a bit of broken clay pot. Even back in Byzantine times she was hard to study. “Both Sappho and her works,” wrote one disappointed scholar, “the lyrics and the songs, have been trashed by time.”

Not everyone was a fan of the erotic nature of her work. A Hellenistic writer from the third or 2nd century says, disapprovingly, that Sappho “has been accused by a few of being undisciplined and sexually involved with women.” A saint and a pope both had her works burned. Tatian, the peach, later called her "a sex-crazed whore who sings of her own wantonness." I’m sure there were a few concerned monks mixed in there, picking out some of the juicier bits.

Over time, people continued to struggle to understand her. Even into the 19th and 20th century, critics were trying to explain away her overt lesbian eroticism by saying it was entirely innocent: just admiration, not desire. No matter how she meant her words to inspire us, they are full of emotion that can’t be explained away, and shouldn’t have to be.

Sappho’s legend has taken on a life of its own; like a snowball rolling down the hills of time, every successive generation that reads it adds on a new layer of meaning. And that’s the thing about literature—once it leaves the writer’s soul and enters the hands of readers or listeners, it becomes whatever they want to make it. As to the woman herself? We may never truly know her, how she lived, or who she loved. But I bet I know what she would say if we could ask her. “I never kiss and tell. But I think we all know I had some sexy adventures.”

Reverie or In The Days of Sappho, John William Godward, courtesy of the Getty Museum

MUSIC

“Ancient Lyre Strings” and “Amatores” by Michael Levy, who plays his music on recreated lyres of antiquity. Pretty amazing stuff! Licensed from AKM Productions Inc.

Theme music composed by Paul Gablonski. All other music from Audioblocks.com.

VOICES

Tawny from The Dirty Bits Podcast. Have a listen to her episode on Sappho, or any of her work: I dare you not to binge it all.

Shawn from Stories of Yours and Yours podcast. He could read from the side of a box of Tylenol and I’d be happy to sit there and listen.

Simon Dinatris

John Armstrong

Avery Downing

Andrew Goldman

Phil Chevalier

Paul Gablonski

![Love_gift_-Love gift Man presents a leg of mutton to a youth with a hoop, in an allusion to pederasty.[1] Athenian red-figure vase, ca. 460 BCE .jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5af1745bf793926c5c8fa04e/1563967658119-B5EXPOZX2X5YTF6QYQLL/Love_gift_-Love+gift+Man+presents+a+leg+of+mutton+to+a+youth+with+a+hoop%2C+in+an+allusion+to+pederasty.%5B1%5D+Athenian+red-figure+vase%2C+ca.+460+BCE+.jpg)