A Lady's Life in Tudor England

The Tudor England we so often see is full of nobles and royals - and we’ll be spending time with them, to be sure - but all that cloth of gold and courtly manners wasn’t what life looked like for most people. So we’re going to begin our season by honing in on what your average Tudor lady’s day looked like. I hope that what we find on our travels will surprise you.

to tudor times we go.

Spinning and weaving wool. Isaac Claesz van Swanenburg, “Het spinnen het scheren van de ketting, en het weven” (1594). Museum De Lakenhal, Leiden.

our guests

Our guests on this series are Ruth Goodman and Elizabeth Norton, both experts on the lives and times of women in this period. You’ll find some of their work listed below, but I also encourage you to check out their websites.

MY SOURCES

BOOKS

How To Be A Tudor by Ruth Goodman

Tudor Fashion & Tudor Textiles by Eleri Lynn

In Bed with the Tudors by Amy Licence

The Hidden Lives of Tudor Women by Elizabeth Norton

The Tudor Housewife & Food and Feast in Tudor England by Alison Sim

The Six Wives of Henry VIII by Alison Weir

Delightes for Ladies to adorne their persons, tables, closets, and distillatories with beauties, banquets, perfumes and waters (around 1600)

“‘Take measure of your wide and flaunting garments’ the farthingale, gender and the consumption of space in Elizabethan and Jacobean England.” by Sarah Bendall, Renaissance Studies Vol. 33

PODCASTS

Dressed podcast’s interview with clothes historian Eleri Lynn: “Tudor Fashion, an interview with Eleri Lynn: Parts 1 and 2.”

Talking Tudors, run by Natalie Grueninger. If you’re into the Tudors, look no further! She’s interviewed SO many experts on the period.

I really enjoyed Noble Blood’s series on the six wives of Tudor king Henry VIII.

Tudor Dynasty has tons of fascinating interviews with experts on this time period. Queens podcast has some fun episodes on the Tudor queens as well.

VIDEO AND ONLINE (wow, is there a lot of tudor content online to enjoy!)

Tudor Monastery Farm, a living history documentary first broadcast by the BBC in 2013. In it, our guest Ruth Goodman and her two co-stars live like Tudor farmers for six months. I tried to pay for it and steam it, but could only find it available on YouTube. You can find it there and I highly recommend it!

The Boleyns: A Scandalous Family. This BBC docu-drama is great: it immerses you in all the drama and intrigue of the Tudor Court while sprinkling through lots of commentary from experts. Our guest Elizabeth Norton is featured as well! The BBC won’t let me stream their website content in my country, but last I checked you could watch at least some of the show on YouTube.

The website On the Tudor Trail is a one-stop shop for all things Tudor. Run by the wonderful Natalie Grueninger of the Talking Tudors podcast listed above.

The Anne Boleyn Files. This is a treasure trove of Tudor information.

To brush up on English history generally, check out the English Heritage org.

The Historic Royal Palaces websites has tons of excellent resources.

“The power behind the throne: women in the Wars of the Roses.” HistoryExtra.

“The history behind the word ‘spinster’.” JStor Daily, and “‘Spinster’ and ‘Bachelor’ Were, Until 2005, Official Terms for Single People.” from Smithsonian Magazine.

“Tudor Money” from Englandcast.com and “The Tudor Market Place” from History on the Net.

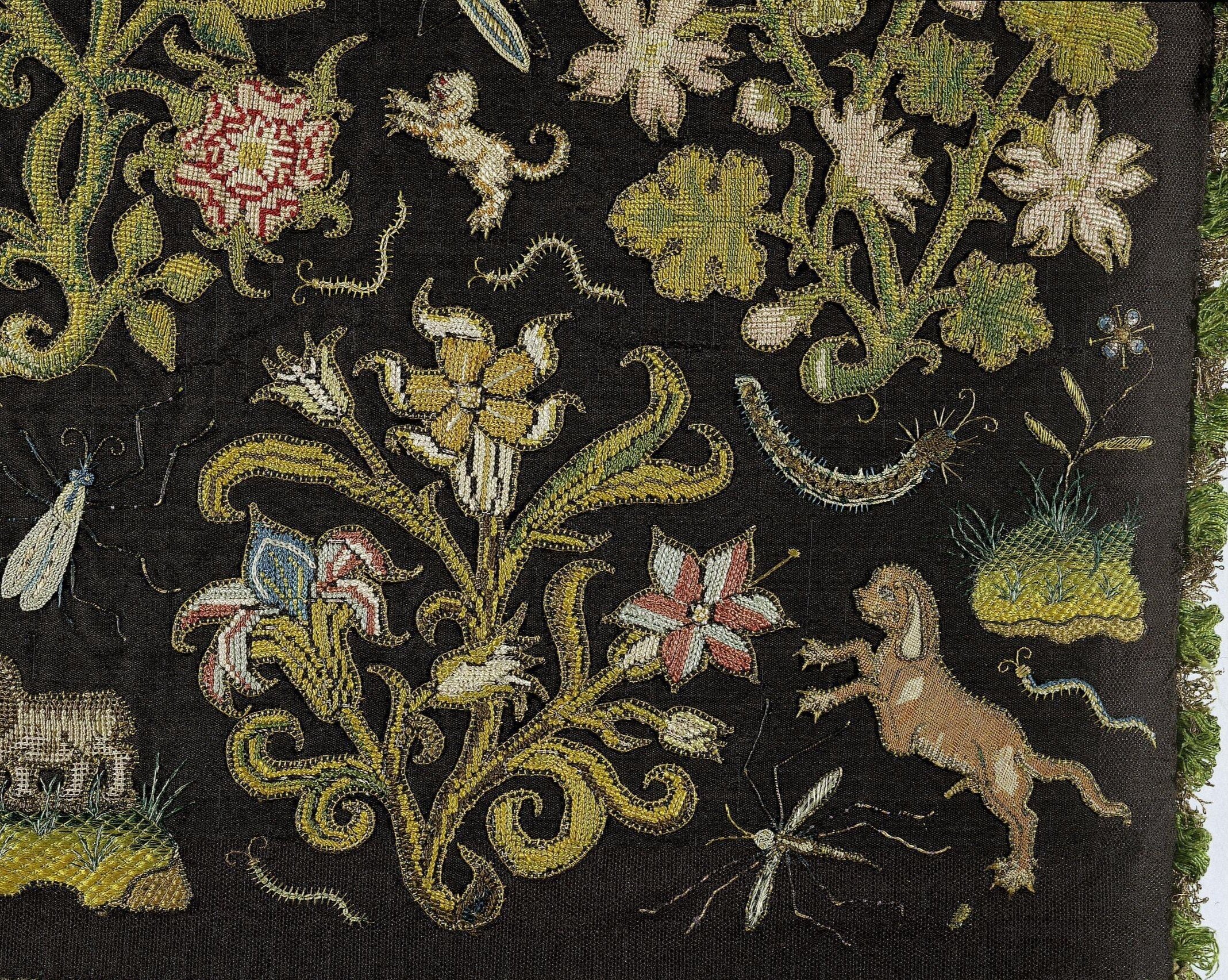

Tudor rose textile (1580), courtesy of the V&A Museum.

Transcript

keep in mind that I edit a bit as I record, so this may not be exactly the same as the audio. close, though.

chapter I: WHERE ARE WE, EXACTLY?

So where are we in history? Most of us know at least something about the Tudor period, but let’s get some context for what kind of world we’re stepping into. The last time we touched down on British soil on this podcast was in 60 CE, where a queen named Boudicca was fighting back against ancient Roman encroachment. Unfortunately for her, the Romans would hang around for quite a while longer, their culture mixing and melding with that of the local Celtic tribes. After 350 years or so, the story goes, Roman Emperor Honorius wrote to the British Romans, saying he didn’t have the resources to protect them; from then on, they’d be looking to their own defences. Not too long after, the Western Roman Empire started to collapse. This shift kicked off a period of invasion in Britain: Irish raiders stormed in from the west, and Picts from the north. But the most game-changing invaders were the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes - all Germanic peoples. Independent, still mostly Roman Britains rebelled against them, but ultimately most of the region would fall under their control. They were the first to identify as ‘English’. Over the years, many of the smaller tribes coalesced into kingdoms. But Britain didn’t become truly united until the scary Vikings came. Starting in the 790s, the Vikings terrorized Britain’s coastline. The Danes, a group of Vikings who came over in the 860s, didn’t just pillage: they put down stumps and stayed. British kings and queens worked to fight off this threat, and sometimes also with each other; no one could agree who should be the one to rule them all. Fast forward to 1066 to the Battle of Hastings, in which Anglo-Saxon king Harold II tried to defend his realm from the Norman invasion of William, Duke of Normandy, aka William the Conqueror. William and his knights won the day, and they transformed England and helped impose Norman rule.

I want you to picture what historians call the medieval period, properly known as the Middle Ages. Knights and their supposed code of chivalry, thatched-roof cottages, the bubonic plague, feudalism, the whole shebang. That’s what precedes the Tudor period. It’s also a time that features plenty of its own powerful kings and queens. William the Conqueror's youngest son, Henry I, brings peace and reform to Britain. But when Henry’s nephew, Stephen, is crowned, despite the rival claim of Henry’s daughter, Matilda, things get messy. Matilda’s son, Henry II, eventually pulls things back in line. I mention him because he’s the first of the Angevin, or Plantagenet, kings. One’s ability to trace their lineage back to this line will be extremely important a few years down the track. He’s also worth mentioning because he ends up marrying the truly magnificent queen Eleanor of Aquitaine, but we’ve gotta fly right past her for now. See you in a future season, Ellie!

Let’s skip forward to the 1450s, when a Plantagenet king named Henry VI is proving to be incompetant at ruling. Rival aristocratic factions, each with their own army, see a chance to take the power for themselves. This kicks off what we now call the Wars of the Roses. This series of military campaigns and epic battles was fought between 1455 and 85, and they involved two royal families: the House of Lancaster and the House of York. They were both branches of the Plantagenet tree, but neither could agree on who should be ruling. For thirty years the crown flies back and forth between them like a shuttlecock, creating both unrest and drama galore. All with clear claims to the throne were killed off; it is not a great time to be a Plantagenet descendant. Unless you happen to be an ambitious and somewhat dubious one who’s spent most of your life staying out of the spotlight. This fellow, a guy by the name of Henry Tudor, is about to change English history. Indulge me for a moment as I tell you how he came to the throne. It’s through his mom, the hardcore Margaret Beaufort, that Henry gets his blood tie to the Lancastrian family, though it’s more than a little murky. There are at least six guys with a clearer claim to the throne than Henry has. But ever since Yorkist king Edward IV defeated the Lancastrians in battle in 1471, Margaret has worked a tireless long game to give her son and the Lancastrians another chance at greatness. Meanwhile, Elizabeth Woodville, king Edward IV’s queen, is suffering a horrid reversal of fortune. After her husband dies quite unexpectedly, her young son Edward is crowned, only to be kidnapped and taken prisoner by his uncle Richard III. Richard claims the throne, has all of Elizabeth’s children deemed illegitimate, and forces them to run for sanctuary, afraid for their lives. It’s a really dark time for this noble clan. But the women of the Wars of the Roses are cunning. Elizabeth Woodville and Henry’s mom, Margaret Beufort, happen to share the same doctor, and through him they pass notes and make a bold, secret pact: if Henry Tudor defeats Richard III in battle, Elizabeth Woodville will recruit all of her husband’s old friends to support him: that is, if Henry swears to marry her daughter, Elizabeth of York, once he’s king. This would be a great deal for Henry, as most people think she has more right to the English throne than anyone. She lends him legitimacy, and he brings Elizabeth’s family back into the royal fold. Plan: crafted. In 1485, Henry sneaks into England with a clutch of soldiers and defeats Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth. Then Henry marries Elizabeth of York, as promised, binding together these long-time rival families. You could say that it’s these clever women who kick off the dynasty and bring a much longed-for peace to the land. Finally, the people of England can come out of their defensive crouches. England is a country emerging from war and stepping gratefully into a whole new age. One that will last for 118 years.

In many ways, Tudor England is still steeped in the medieval: the way most people live harkens back to earlier, Middle Age times. But this is also a time of profound growth and change. When Henry Tudor seized the throne, there were fewer than two million people in England, and maybe another half a million in Wales. By the time Elizabeth I dies, it’s estimated that those numbers will double. London’s population swells from 50,000 to some 200,000. As the population grows, so does England’s importance as a cultural powerhouse. It’s important to remember that, even amidst all the medievally king slaying, the Renaissance is happening over in Europe: a flowering of art, thought, and culture that will influence England profoundly.

With all of that swirling in the back of your mind, let’s touch down in summer, 1535. King Henry VIII is 44 years old and has been ruling England for 26 years. He's on his second and perhaps most scandalous wife, Anne Boleyn, but he’s only a year away from ordering her execution. But let’s not focus, for now, on kings and queens. Let’s explore a day in the life of your average lady in Tudor-era England.

chapter II: THE COCKEREL CROWS

As you lay in bed, preparing to wake, you might think you’ll be opening your eyes on life in London. But in truth more than 90 percent of the population lives rural. Agriculture is our country’s bread and butter industry, quite literally, and even those who aren’t working farmers do at least some to feed their families. Statistically speaking, very few of us are going to be born into anything even close to nobility. We will spend our lives working the land - and working hard.

Rise and shine, Tudor lass! Given that we don’t have electricity and the sun is all we’re likely to have to see clearly by, we’ll be rising with the sun. It’s summer, which means we’re looking at a 4AM start. *Shiver*. But we Tudors don’t like a so-called “slugabed,” so no lying about. There’s nothing for it but to get moving.

What kind of dwelling are we waking up in? In this, as in everything, our wealth and social status will dictate much of our surroundings. Many of us are waking up in timber-framed, thatched-roof houses, with walls filled in with wattle, daub, and...well, probably some creepy crawlies. What IS wattle and daub? I’m glad you asked! To make such walls, we hammer a bunch of wooden planks or sticks into the ground, and then we weave wattle - thin branches harvested from local trees - in between them. You’re essentially weaving yourself a wall. Then you plaster the whole thing over with a pungent mix of clay, horse dung, and straw. How delightful. When it dries, though, you have a surprisingly nice, smooth, and draft-proof wall. It’s not nearly as rustic as it sounds.

Woo, it’s brisk! We’re in England, after all, which doesn’t see a whole lot of balmy days. Whether you’re living in a thatch-roofed Tudor cottage, a city townhouse or a fine castle, insulation is not what our modern-day sensibilities might prefer. In fancier houses, the walls are probably covered with brightly painted panelling and tapestries, which helps keep things warm in winter. Most of us don’t have glass windows; they’re a luxury product. We’ll rise to brisk morning air working its way around the oil cloth shutter we use to cover our windows, there mostly to keep out the worst of the rain and wind. So yeah...you’re going to want to rug up, or sleep close to our main heat source; the fire. Here’s Ruth.

RUTH: So at the beginning of the Tudor period, almost everyone, with a very few exceptions in castles and monasteries, almost everyone lived in a space that was open right up to the roof. There weren't floors, you know, up and down, it was just one space from the ground floor right up into the apex of the roof, and in the center of that space would be a fire on the floor.

This is pretty efficient, from a heating point of view; you don’t need a huge bonfire to heat your cottage, and these central fires make for convenient 360-degree cooking. The problem is that the smoke rises up and hangs in a sting-inducing layer above you. That is why, at least for the first portion of the Tudor period, most of us are sleeping not in a raised bed, but on the floor. Anyone who’s ever gone on a badly planned camping trip will know this can be an uncomfortable situation. But in Tudor times, it’s not as bad as it sounds.

RUTH: ...they have almost no furniture, everybody's on the floor. But that means you need to make the floor comfortable. So people laid rushes on the floor, a big thick layer of dried rushes. It's like living on a permanent mattress. You know? Imagine a really thick carpet or some, you know, cushions on the floor. That's what people were basically living on…

Rushes are a kind of reed, very plentiful and cheap to find, which are collected from nearby waterways.

RUTH: You harvest them out late summer, before they start to dry off when it's still quite, sort of, you know, fresh and green. You don't wait for them to brown. You cut them and then you dry them. They need to dry out completely. And then you can lay them as they are. It's best not just sort of wildly scattered when you lay them in bundles...or you weave them into something that's going...a mat that's not going to, you know, go anywhere, not move around.

Instead of just throwing rushes down, most people are taking the time to braid them into floor rugs. Time consuming, yes, but loose rushes are a nightmare for skirts. No one likes bits of reed stuck in their hems, ya know? Rushes have a decent air pocket inside them, which can make a bed of rushes almost like nature’s blow-up mattress.

Details from a tester, a lovely part of a four-poster Tudor bed, from between 1550 and 1570.

Courtesy of the Victoria & Albert Museum.

RUTH: Even under pressure, that is creating an air pocket. So it's very, very insulative, and also bouncy and squashy. So you've got the comfort of the slight give, and you've also got the insulative warmth of all those little air pockets. It’s comfortable and quite clean...If it got disgusting, you could just throw it away. You know, it was compostable, you just swept it out, and you put a new load in.

Sometimes rush floors are swept out and replaced all the way down to their foundations. But that’s a lot of work, so most people freshen things up by putting down a new layer of rushes over the old. The very bottom layer may have been with you for...a very long time. Which is worrying, given that this is the floor we sleep on, eat on, cook on, you name it. In 1515, a Dutch man named Desiderius Erasmus wrote that many a floor is renewed: “so imperfectly that the bottom layer is left undisturbed, sometimes for twenty years, harbouring expectoration, vomiting, the leakage of dogs and men, ale droppings, scraps of fish and other abominations not fit to be mentioned.” Keep in mind that this guy was extremely homesick when he wrote this and not a fan of England, so he wasn’t in a very charitable mood. But he might have a point: when your dog pees on your carpet, there’s that part of you that just KNOWS it’s seeped down into layers that your scrub brush just can’t reach. Aren’t rushes the same? In a word: no.

RUTH: The surface of each stem is a very sheer surface, which dirt has trouble sticking to. So if you drop food or anything else onto rushes, you know, it doesn't soak into the rushes, it tends to sort of like just fall between and stay quite sort of separate. So cleaning is quite an easy thing to do.

Ruth experimented with a rush floor when she worked on Tudor Monastery farm. She found that if she laid the rushes two inches thick in an enclosed room and wet them occasionally, they stayed green and fresh. When she went to clean up the floor after six months of people walking, eating, drinking, and sleeping on it, she said the bottom layer was clean as anything.

RUTH: The other thing to remember is that these rushes would be put upon bare earth, they're not being put upon stone flags, they're not being put upon a wooden floorboard, they'll be put on bare earth. And that means that natural composting is going to happen at the base, it's going to happen quite slowly, because it's quite a dry environment - you've got a roof over your head, obviously. But very slowly, the bacteria and small animals within the soil are going to be breaking down at the base of the rushes. It's a slow, dry, quiet, and very clean-smelling form of composting.

The same can’t be said for your modern-day synthetic carpet. Natural Tudor products: 1, modern products: 0.

As the period goes on, though, we see a pretty new-fangled technology take root: chimneys. Chimneys start to make the floor a cold place to sleep, so we take our rush mattresses up onto wooden frames, held there by a rope strung back and forth lengthways to create a kind of mattress hammock. If this ropes get loose, you’re going to have a very saggy sleep situation. So you’d better keep that rope pulled taut so that, as we still say in our era, you can “sleep tight.”

The word ‘bed’ doesn’t mean the frame your mattress sits on: it means the mattress itself. The humble amongst us are probably sleeping on a large, straw-stuffed pillowcase mattress. It’s not as bad as it sounds if you choose your straw wisely. There’s a whole family of plants known as ‘bedstraw’. The finest of them is called galium verum, or Lady’s Straw. It’s soft, smells nice, and helps repel rodents. Your mattress might also be made of flock, or wool, but if you’re a fine lady, you might have a feather bed. You might even wake up on SEVERAL mattresses piled on top of each other.

If we’re noblewomen, we’re probably sleeping in a four poster: a bed whose frame has four posts, a ceiling made of cloth or wood (called a tester), and nice, thick, closeable curtains.

Our windows don’t have curtains, but our beds sure do! This bed, no matter what it’s made of, is likely to be one of our most prized possessions. It’s one of the things most frequently bequeathed in people’s wills. Shakespeare gave HIS best beds to his wife and his eldest married daughter: he could die knowing they’d be comfortable, but also that they’d have something of true value. A high-quality, fully decked-out four poster can cost as much as a small-time farmer’s holding. Think about it: when your house doesn’t have great insulation, it’s like a little luxury cave: dark, warm, and snug. AND it affords you some privacy, a thing we are unlikely to get a lot of. Most Tudor homes don’t have corridors; to get from one part of the house to another, people just walk through rooms. No one’s yet come up with the idea of servant’s quarters, so the whole household is often sleeping in the same space - a holdover from the Middle Ages. That four-poster bed with thick, probably woolen curtains blocks out chills, but also farts, snores, and...whatever else might be happening. This bed is a rare and special gift.

Of course, the chimney starts to change that. It not only gets us Tudors up off the now-drafty floor, but changes the way we build our houses.

RUTH: ...you start chopping up living spaces into much smaller into rooms into separate little rooms. However, you can also put in floors because there's no smoke up in that roof space now. So suddenly that roof space becomes usable. So instead of living in one big space, you've suddenly got a multitude of little spaces, including extra little spaces above a first floor, a second floor, possibly...So it's a major change in the whole way we organize our living and beds were part of that huge upheaval.

chapter III: first thing’s first

Snug in your fourposter, you probably don’t want to get up at this ungodly hour, but God demands it; it’s time for prayer. Religion and religious institutions are the bedrock of our society. Its presence is felt in good times, at christenings and weddings and festivals, and in hard times. Abbeys, and nunneries are in every town, feeding the poor, offering work, and taking in the sick. Our religion is deeply felt and deeply important to us. It impacts everything, from how we educate our kids to how we spend our time. Separation of church and state? Hell no. In this age they’re hopelessly, and often thornily, entwined.

A woman’s chief duty is to be Godly, and to teach her family to be the same. Gervase Markham, who wrote a guidebook for women in 1615, says that we must be “of an upright and sincere religion, and in the same both zealous and constant.” But constant to which religion: Catholic and Protestant? What is the correct and proper way to pray? These are some of the most fraught and pressing questions of this era. When we kicked off the century, England was Catholic. Very Catholic. But just one year ago, Henry VIII broke with the Pope, who wouldn’t grant him leave to divorce his first wife. In 1534 he declared that HE should be England’s final religious authority. He established the Church of England and dissolved England’s monasteries. Old icons are axed, new prayer books printed. We’re in the middle of a profound religious shakeup that will impact our way of life for decades. But we’re going to find religion more fully in a future episode. For now, just know that religion is considered a cornerstone of life for women. A love of God, and educating our children in the ways of religion, are expectations that Tudor wives and mothers will keenly feel.

TO THE PRIVY

Now that we’re good with God, it’s time to freshen up. Skin, hair, teeth: they all need our attention. But first, let’s have a quick morning pee. Where are we going to be doing our business? There are some plumbed privys in Tudor England. Henry VIII has plumbed bathrooms with running water installed at several of his residences. At Hampton Court, he’ll even build the Great House of Easement - a four-tier, 28-seat communal latrine over a moat. It’s not unlike the bathrooms we encountered in Ancient Rome, come to think of it. Of course this particular poo palace is for Henry’s courtiers: he has his own private chamber, and his own bathroom attendant. That guy even has an official title: the Groom of the Stool. In 1539, this guy will record one of the king’s 2 a.m. bathroom episodes, the result of taking laxatives and an enema before retiring: “when His Grace rose to go upon his stool which, with the working of the pills and the enema, His Highness had taken before, had a very fair siege”. TMI, Stool Groom! His daughter, Elizabeth I, will also have a bathroom attendant, Katherine Ashley, though her title is Chief Gentlewoman of the Privy Chamber. This queen will commission one of the first prototypes of the modern indoor toilet - the water closet - invented by her godson John Harrington. He isn’t the first to design a flushing toilet – Londoner Thomas Brightfield did that in 1449 – but he is the first to write down plans for one. But given water supply and plumbing issues, this won’t really catch on for a very long time. Most of us, noble or commoner, will use some form of chamberpot. Many will have privies, which are essentially a piece of wood with a hole cut into it, placed over a bowl or a hole in the ground. In castles, you’ll go to a particular cupboard and sit on what looks like a toilet seat, but there’s no flushing involved: your business is whisked away by gravity, falling down through the air and into the moat below. Please remember this moment later, when the day gets hot and you’re pondering a cooling swim. In cities like London, many dwellings share the same communal privy, so it’s no wonder that we’re likely to pee in a chamberpot. But what exactly are we wiping with? Ruth thinks paper is a likely option.

RUTH: So, we know that some paper was used in the toilet...But I mean, just having the paper, you know...that's all very well, in the city of London, perhaps where there are lots of balance sheets, you know, knocking about, there is sort of what you might call scrap paper. But if you're in the countryside, that's less of a viability. Now, many people postulate that people use leaves or moss. But again, you just have to think of practicalities, I mean, how many fields of moss would you need to keep a family?

Fair enough. The most likely option, then, is cloth. Ruth thinks we’re probably wiping with linen. Given how expensive cloth is, though, your linen wipe isn’t going to be one use only. You’re going to wash that baby out and reuse it. Ruth has a theory as to what this might look like.

RUTH: I mean, you wouldn't want to share such things. But you might have had a cloth, perhaps it hung on a nail in the privy: that was yours, and you wiped yourself and then washed it out.

Imagine our family’s bum cloths, all lined up in our privy. I dearly hope you have some way of knowing for sure which one is yours!

While we’re in the privy, let’s talk briefly about periods. For those of us who menstruate, what are we using to deal with the flow? Sadly it’s not something we Tudors write about in great detail - or at all. There are references to rags attached to belts that would be worn under our outfits. Just like with toilet paper, the most practical solution will be linen rags.

RUTH: The other possibility is a homemade tampon. Again, if you take the little strip of linen, and you roll it up into a sort of like little hard cylinder, with one and a half, three, you have got , for all intents and purposes, a linen tampon, which can be used exactly like you would use a modern tampon. And again, you can watch it out afterwards.

One medical treatise from the 17th century talks about tampons - or rather pessaries, made of wool, linen, or even silk, sometimes infused with herbs. It’s unclear whether these are specifically for menstruation or medicine. One thing’s for sure: if you’re a hard-working farm lady, the linen tampon might be the most convenient. Just make sure to wash it out, quickly and thoroughly, and you’re good to go.

chapter IV: GETTING CLEAN

So, on to washing. When we talk about history, we often think they must have suffered a high level of stinkiness. But if we stop and think about this for more than three seconds, it doesn’t make a lot of sense. Few people of any time period WANT to walk around covered in dirt and smelling like overripe melon. It turns out that your average Tudor cares a LOT about personal hygiene.

RUTH: So firstly, I'd say that people talk about cleaning a lot. It mattered to them, they minded. There are jokes and stories and disgusting reports of people who were not clean/ "Stinking beasts" are mentioned. People talk about somebody who smells. So clearly there were differences between those who smell more, and those who smell less, or those who smell what was considered to be good and those who smelled what is considered to be bad. So that's the sort of starting frame, people cared about personal hygiene, they cared about smell. They cared about it on health grounds, as well as on the pleasantness of being around grounds on manners and so forth.

But are we likely to soak in a full-body bath? Heavens, no! We’re working with the miasmatic theory of disease here: the idea that evil miasmas float around on the air, carrying plague and other nasties, which enter through the pores of our skin. “Use no baths or stoves,” Tudor physician Thomas Moulton writes. “Nor sweat too much, for all openeth the pores of a man’s body and maketh the venomous air to enter and for to infect the blood.” If you believed that your skin was one of the most important barriers between you and infection, and that closing off your pores would protect you from plague, OF COURSE you’d be leery of frequent full-body washing. But that doesn’t mean we aren’t interested in cleanliness - in fact, we Tudors are fairly obsessed with it.

Most people will be taking sponge baths rather than immersing themselves in any tub. We will begin by washing our faces and hands with clean, sometimes perfumed, water. There are lots of facial washes recommended for skin issues. Have pimples? Sir Hugh Plat, in his 15th-century household manual Delightes for Ladies, offers remedies that range from the fairly gentle - mix salt in some lemon juice, then wet a linen cloth with it and pat the face as needed - to the fairly intense. “Brimstone ground with the oyl of Turpentine, and applied to any pimple one houre, maketh the flesh to rise spungeous, which being anointed with the thicke oyle of butter that ariseth in the morning from new milke sodden a little ouer night, will heale and scale away in a fewe days, leaving a faire skinne behinde.” Oh my.

Washing our feet is among our most crucial morning routines. Though we Tudor ladies don’t have to worry about smelly feet as much as the modern woman, as our pure wool stockings and leather shoes are breathable and antibacterial; unlike synthetic sneakers, they discourage infection and let sweat dry out. There are heaps of recipes for soap floating around in our household instruction manuals. Sir Hugh gives a recipe for a “washing ball” made out of castille soap. The wealthy tend to stay away from soap altogether, as it’s often made with things like tallow and potash, opting for so-called “washing water” instead. This is essentially water infused with herbs like sage, rosemary, and orange peel.

Though most people will only be washing their hands, faces, and feet on the daily, people ARE taking full-body baths in Tudor England. Henry VIII takes hooped, portable tubs with him wherever he goes. London’s public baths will open up in 1564, and the town of Bath has been using their Roman-era baths for even longer. But given the baths’ connection to vice and a dangerous level of pore opening, we ladies are unlikely to spend much time there. Elizabeth the First will be quite fond of the private baths her dad builds at Hampton Court, as well as the steam bath at Richmond Palace. But spa time isn’t just for royalty. For the lady looking for a little steam at home, we have somewhere to turn. In Sir Hugh’s Delightes for Ladies, he suggests the following: bore some holes into our tub. Then we’ll grab a lidded brass pot and make a hole in its lid, just big enough to fit a lead pipe through. Add in some herbs and water, put it on the fire, and when it’s nice and steamy, put it under your holey tub, climb in, and put a sheet over your head. The steam will rise up through the holes and envelop you in its cleansing goodness. Though Sir Hugh makes sure to warn us to be careful, as any drafts might “offend you whilest your bodie is made open and porous to the aire.”

But again, this is likely to be a luxury rather than a regular occurrence. So what does a Tudor lady smell like? Do we just need to accept a certain level of stink? Let’s ask an expert.

RUTH: Well, I've tried it. I've tried it in two contexts. I've tried it in a modern context, and I've tried it in a tutor context.

Ruth wore a linen smock, or shift, and period-appropriate woollen tights under her modern-day clothes. She changed them daily, and also did what Sir Thomas Elyot, in his book on good health from 1534, suggests: “rub the body with a coarse linen cloth, first deftly and easily, and after to increase more and more, to a hard and swift rubbing, until the fleshe do swell, and be somewhat ruddy…” This is meant to bring toxins to the surface of the skin and draw them out through the pores. During this time, Ruth didn’t bathe or shower...for months. And guess what?

RUTH: And that was okay. It was okay. There was a slight smell. There was a slight, you know, if you were in a heated central heated office or somewhere I think they might mind...but if you were sort of out and about, or in your own home or whatever, it was possible. Most people didn't recognize that I was doing it for six months. And I got no comments whatsoever.

Ruth tried it again while filming a Tudor-era documentary - the excellent Tudor Monastery Farm. Again, no showers, no soap, no washing her entire body. She changed her linen smock and head wrap only once a week.

RUTH: I was wearing entirely period clothes. So this time, it wasn't like modern clothes over the top. It was the full Tudor stuff. So it was all linens and wools. We were outside and it was around fires. Again, nobody noticed. Nobody noticed. I did it for six months...so it's clearly a viable system.

A colleague of hers, though: he took daily showers with modern hygiene products, but pretty much never changed or washed his underwear or outfit. Ruth describes his scent as, in a word, “overpowering.”

RUTH: He didn't change the clothing. And, and, and the clothing started to really stink. Really stink. I mean, he was clean. But his clothing wasn't. And everybody commented on it…[laughter]...We actually had a little cabal and we stole the clothing and washed it.

Ok, so what’s the deal here? How do we stay fresh without regular applications of hot water and body wash? The answer is twofold: the power of linen and how regularly it gets laundered. Since we Tudors believe that diseases come from the air and pass through our pores, one of the best ways to stay healthy is to keep as much of our bodies covered as possible. No matter who you are, queen or pauper, you’ll wear a full layer of linen underneath your clothes. Smocks, hose, cuffs, caps: this natural base layer helps keep you warm in winter and cool in summer, and it’s a mighty barrier between you and the filth of the world. It’s breathable. And when you ‘shift’ this layer, aka take it off, it’s believed that you pull dirt and grease away in the weave of the cloth.

RUTH:.... they're not, it's not like, you know, an antiseptic as such, but there are inhibitors, bacterial inhibitors within natural fibers, both wool, linen and cotton, linen more than cotton.

It’s also easy to wash, and that’s crucial.

RUTH: you don't really wash the body, you wash the clothes. Outer clothes you can't really wash - you wouldn't wash an overcoat, would you? So it's this underlayer that's getting washed. And the more frequently you can wash, the better.

And so we are fastidious about changing and laundering it daily. The wealthy ladies amongst us might change their linen several times a day. It’s a point of pride, to wear clean linen. Those who don’t, writes contemporary Richard Jones, might be jeopardizing their relationships. In his book about how to have a happy marriage, he says that a woman who wears dirty linen “shall neither be prazed of strangers, or delight her husband.” And it’s true that linen undies help keep us stink-free.

RUTH: And if you think about it scientifically, that makes sense, doesn't it? Body odor is created by bacteria who are feeding on the sweat of your body, it's not the sweat necessarily that smells it's the bacteria feeding on it that produces the smell. So clothing holding that sweat is going to be much more somewhere where body odor collects and is created that is actually on your skin. So you know the changing of clothing is really important…

Natural fibers = 2, synthetic fibers = 0.

We Tudors also want to make sure our breaths are taken care of. So we’ll clean our teeth, not with a brush, but with a cloth and some kind of tooth powder. There are plenty of recipes for making your own. For a whitening mouthwash, our friend Hugh Plat suggests we boil a mixture of honey, vinegar, and wine. You know what else is good at whitening AND cleaning your teeth? Soot, apparently, preferably from a wax candle. It’s easy to come by: just hold your candle’s flame against a clean, polished surface, like a mirror or glass pane. Done! It’s a soft abrasive and a deodorizer, too. You might also try salt or chalk. Some recipes add perfumes to the equation, filled with herbs like cloves, which smells nice, but also serves a medicinal purpose: it eases pains, and mouth pains aren’t uncommon.

We’ll take our love of nice scents even further with a bit of perfume. We Tudors love perfumes; we believe that when scents enter our bodies, they go up our noses and past two nipple-like organs at the tippy top of them, traveling on to a kind of net around our brain. What scents we’re breathing in can impact our health and our spirits, so best make sure they’re always good. Most people get their scents from natural sources: rosemary for memory, lavender for a good night’s sleep, herbs burnt on the fire. Such things can sometimes be expensive. Robert Dudley, Queen Elizabeth’s favorite and the Master of her Horse - yeah he was! - spent about a pound in 1558 on herbs to strew around his chambers. Some scents will be associated with particular times and places: frankincense will make us think of church; wormwood, a pungent herb used to keep out vermin, might make us think of cleaning. Romance-inducing rose oil is the signature scent of Henry VIII. It requires a huge number of petals and is expensive to come by, even in the modern era, so if someone gives you a perfume bottle filled with it, you’ll know he’s courting you pretty hard. The most common form of perfume is a solid, and it comes in the form of a pomander: a small pouch or perforated container filled with herbs or a solid scented ball. It is tied around our waists or worn on a chain around our necks so we can bring it up to our noses when we happen upon something offensive smelling. After all, we believe that disease is often carried on the wind within bad smells, so this is about health as much as confort.

chapter V: LET’S GET DRESSED

Now that we’re well rubbed and fresh, it’s time for dressing. What do we pull on first? What we wear, and particularly what type of fabrics, will depend a lot on our level of wealth, our social station, and the slice of Tudor history we’re time traveling back to. But we’ll all be starting with the same basic base layer: it’s that staple of our wardrobe, the linen smock, which we will later call a shift, and even later call a chemise. Yes, we DID wear a chemise when we went to Victorian America in Season 1. Good memory! Picture a simple nightgown: two rectangles of linen sewn together, with two triangular bits sewn in at the sides to give it a bit of shape. This will serve as our underwear. Sure, there are European ladies who wear boxer shorts like the men do, but there’s a whiff of the courtesan about it. So if you want to start a scandal, you feel free.

The linen smock serves a lot of functions: modesty, hygiene, and comfort. Linen is made from long fibres like jute, hemp, and most commonly flax, making it strong, soft, and breathable. Hot Tudor tip: it also tends to get cold, so if you have servants, you might ask them to warm it for you of a morning, or you might pull it into bed with you to take the chill off. Our smock tends to capture our sweat, which is good, because it’s the only layer of our clothes strong enough to hold up under frequent washing. That’s why many still call laundry baskets ‘linen baskets’ today. Given that most of us can only lay claim to two, maybe three pairs of underwear, we can see why they’ll be washed pretty often. Most of us are lucky if we have one smock to wear, one in the wash, and maybe a fancy one set aside for Sundays.

You’ll know, if you listened to my bonus episode on the subject, that we won’t wear a bra. No matter. As we’ll see, our outer garments will give us all the constraints we might want.

Our hose come next. While men’s hose tend to be on display, we want ours covered up. They’re more like knee socks than panty hose. It’s likely they’re knitted: wool for most, and silk for the fanciest amongst us. No matter how crude or fine, though, they have no spandex in them, and that means you’ll need a garter at the knee to hold them up, either knotted or closed with a teeny buckle.

So that’s our base layer. Where we go from here, clothing wise, depends a lot on our station. We’ll get dressed with a royal later on in the season, but for now, let’s cover the basics of what your average lady might wear.

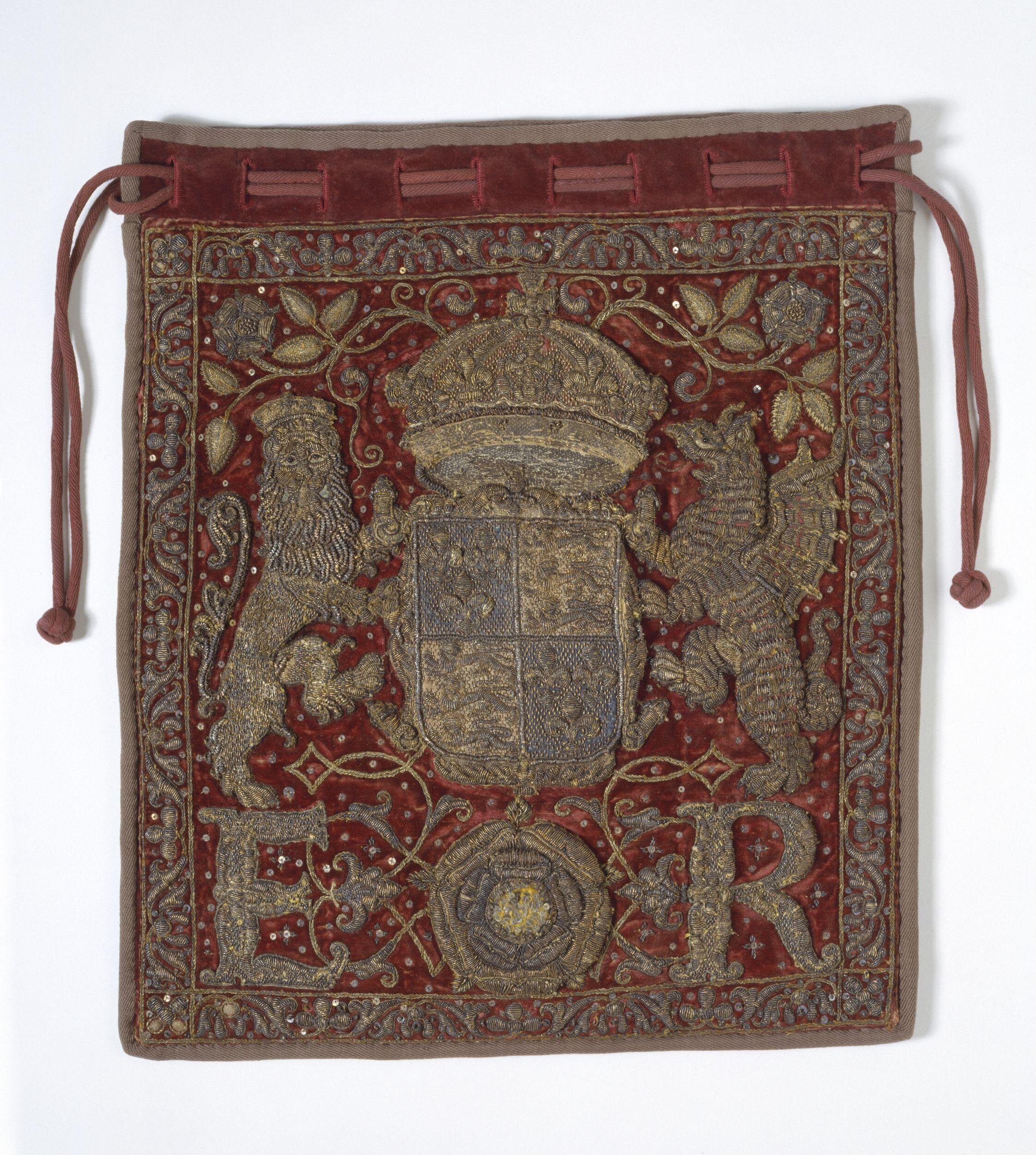

Detail of an embroidered linen shirt, 1540, shows how talented seamstresses could be at this time.

Courtesy of the V&A Museum.

First, we’ll slip a kirtle on over our smock. The kirtle is a full-length dress with a skirt and a snug-fitting bodice given shape with a lining of canvas or buckram and often reinforced with wooden rods or even whalebone. To get it situated, we lace it up the side or back. How to lace it if your ties are behind you? You use a spiral lacing technique. I’ll show you. Ready? See all those eyelet holes in your kirtle and that long piece of cord? You’re going to lace up your kirtle by going around in a spiral, not criss-crossing like you’d do with your modern running shoe. Do this while it’s still laid out on your bed. Then shimmy under and into it while it’s loosely laced, and once it’s where you want it, pull on the end of your long lace to slowly tighten it, shimmying and jiggling everything into place.

We might stop here, if we’re a working woman. The kirtle is modest and sturdy, usually woolen. It keeps us warm and is thick enough to protect against stray sparks, thorns, and the sun. But we can also fancy up our kirtle, should be choose to: by our choice of material, say, or with the addition of beadwork or embellishment. We can also dress things up by wearing a gown over the top. The gown, which usually laces up the front, will generally be lower cut, with that Tudor-signature square-cut neckline, and shorter sleeves. The gown has a big slit that starts around the navel and drops to the floor, which reveals flashes of your stylish kirtle. OR it might show your forepart. Picture a square of fabric that you pin over your kirtle, kind of like a false apron: that’s a forepart. Tudors are fond of adding detachable, mix-and-match details to their outfits, particularly in fancy fabrics: detachable sleeves that match our forepart are a favorite. Why? Because as we’ll talk about shortly, fabric is crazy expensive. These detachable extras let us jazz up our outfits without breaking the bank.

The other bit of flair we might add on is called a placard: a stiffened piece of chest armor that’ll cover up the front ties of our gown and give us the rigid shape that comes to mind when you picture Anne Bolyn. These are particularly handy if we’re pregnant, as we can lace our gown quite loosely and no one will be able to tell.

Another wardrobe staple for the non-working women is a farthingale. When Katherine of Aragon, Henry VIII’s first wife, sailed over from Spain, she brought the farthingale with her. The term comes from the Spanish word verdugos, which is used to describe the smooth willow twigs that’re sewn into these skirts to make them bell out a bit from a woman’s legs. It’s basically an early form of hoop skirt. It gives us the desired silhouette of the time, but also allows us ladies to take up a little more space and make a statement. And if our king Henry VIII loves one thing, it’s flash.

But I don’t remember hearing mention of buttons or zippers. How are we keeping all these layers on our person? With the help of a WHOLE LOT of straight pins. There’s a reason we ladies need our “pin money”! A Tudor outfit, for both men and women, is essentially stitched together every morning piece by piece. A laborer might only need four of five pins to hold together her clothing, while a lady hanging out at court might need a thousand. During her reign, Elizabeth I will have some 24,000 pins of different sizes delivered every six months. We might also fasten our clothes with ‘points’: short strips of leather, cloth, or braid, with metal points on both ends, kind of like our modern shoelace. Most of our points are made of silk and braided. They’re strong, shiny, smooth, and a pretty affordable touch of luxury. They also make an inexpensive courting gift.

Ok, we’re dressed! But don’t step too close to the fire; we Tudors go to great lengths to keep our clothes in good condition, because our clothes are precious to us in a way that we might struggle to fathom, but it’s one we should spend some time chewing on.

A LUXURY MOST CAN’T AFFORD

In this era, clothes are crazy expensive. That’s in part because of how they’re made. The costs of processing the raw materials, not to mention the making of the garment itself, are truly enormous. Most of England’s rural landscape is devoted to sheep rearing and the production of wool - it’s a staple of most of our lives, and accounts for about half our nation’s wealth. And yet without modern-day electric shavers, fleecing these sheep is a major operation. Today, a skilled Australian shearer might get through 200 sheep in a day; the 16th-century shearer, working with hand shears, maybe 30. The fleece has to be beaten and hand sorted, a task often relegated to women and children. We’ll have to painstakingly pick out grass, twigs, and...you know. Dingleberries. There are several more steps: separating rough wool from fine, combing and oiling it, before we get to spinning. This is an important job, and one done almost entirely by the ladies. It’s done with a spindle and distaff, usually by hand, but it might also be done with a spinning wheel or a walking wheel, so called because the spinster has to continually walk back and forth as she’s spinning. This job might have us walking up to 30 miles in a day. Spinning is often done at home, which might provide the family with a little extra income. Someone who spins for profit is called a “spinster.” This term first showed up in the mid-1300s, and it becomes very gendered, because most spinsters are women. For perpetually single women, it’s one of the only jobs they have ready access to. That’s why, by the time we get to the Regency era, the word “spinster” is used to describe that dowdy-looking dame by the punch bowl, single and well past marriageable age.

It takes twelve skilled spinsters working hard to produce enough yarn to keep a (usually male) weaver in business. It might take him six weeks to produce a single piece of cloth. The next step is fulling, which cleans and whitens the cloth. Know what we’ll be using to do that? Giant vats of urine. Hey, it was good enough for the Romans! If a dyer gets involved, they’ll dip the cloth in natural dye, then beat or trample it to tighten the weave. Then they’ll stretch it on a tenter, or wooden frame, with special hooks called tenterhooks. The point is to stretch it taut so it dries at certain, legally mandated dimensions. You know when someone says they’re “on tenterhooks” - aka nervously waiting, stretched taut in suspense? This is why.

Remember, too, that we aren’t buying ready-made clothes in this era. Hats, stockings, and gloves you might buy as finished products, but pretty much everything else is made to order. You have to buy the cloth, THEN pay for a tailor to make something for you. You can see why even the most basic outfit costs a decent coin.

Let’s put this in perspective. In Tudor times, a guinea is worth 1 pound and 1 shilling; a pound is worth about 20 shillings; a shilling is worth 12 pence. Toward the end of the 16th century, an average day-laborer's wage will be six pence. A loaf of bread will cost you about a penny. But a basic canvas shirt will cost around two shillings to have made; that’s about four full days’ work for the laborer. Even a worn-out secondhand shirt that you’re going to use as a dishrag is worth about two pence, or a third of your day’s paycheck. Clothes are in many ways a luxury item - a way of showing off your status as well as clothing your body. Take Robert Dudley, Queen Elizabeth’s favorite. He will pay the same amount for one of his suits as William Shakespeare will pay for his house in Stratford-upon-Avon just a decade later. Textiles and clothes underscore the huge monetary gap between the humble farmer and the nobleman. Henry VIII can afford to pay 1,500 pounds for ten tapestries to decorate his walls, while a skilled shipwright will make around 12 pounds...a year. And these weren’t even Henry’s finest wall hangings.

What our money can buy in Tudor times is different from what we’re used to. In our era, food costs consume around 17 percent of our total income, but in a Tudor household food dominates most people’s expenses: we’re talking around 80 percent of our income. In other words, we can’t always buy clothes AND ale for our family. Our margins are forever miniscule, and so we have to make each shilling stretch. No wonder second-hand clothes are big business across all social classes. Clothes are so valuable that they’re their own kind of currency. We don’t have banks in Tudor England, but that pair of silk hose can be converted to cash by sale or pawn. A lot of people move their nicest outfits in and out of pawn, using it as a kind of loan library. In the late 1590s, theater manager Philip Henslow will lend one Mr. Crowch 3 pounds 10 shillings against the security of his wife’s nicest gown. Clothes are often bequeathed in people’s wills, passed down to family members who can have them tailored. You won’t ever ditch a kirtle because it has a hole in the armpit. You’ll patch, mend, and alter it. This is not an age of fast fashion or throwaway clothes.

It’s handy, then, that our outfits are made of many separate pieces. It means we can mix and match them to make our outfits feel new. A woman might have several sets of sleeves, say, that she can wear to give her look a fresh feeling, or a forepart might give the impression of a totally new kirtle. Even queens do this - especially queens, as they’re expected to look lavish and to never wear the same thing twice.

We’ll talk more about clothes in a future episode, but for now there’s one more thing we Tudors need to keep in mind as we dress. Henry VIII has introduced some sumptuary laws: legal mandates that actually say who is allowed to wear what. Though most of these will only apply to men until the 1570s, when Elizabeth the First takes the throne, they're still important for us to be aware of because of how they influence our interactions with others. We’re living in a time that believes firmly in a clear social hierarchy and keeping everyone in their proper place. How better to tell at a glance who is who than by strictly policing who’s allowed to wear what? These laws make clothes a visual signifier of your rung on the social ladder. They ‘place’ you, telling others how they should interact with you. Dressing above your station can get you into serious trouble, though such things can be hard to police. Hence the rise in criminals who pull off their jobs by dressing as someone above their station; if someone dressed like a nobleman asks you for something, you’ll likely do it without question. Never has identity theft been more easily achieved.

HAIR AND MAKEUP

Once we’re dressed, we’ll get out a brush and untangle our hair. We won’t have washed it with anything like the shampoo we use today. How do we keep it from getting all greasy?

There are people in our era who argue that shampoo is part of the problem, not the solution. Shampoo strips the grease and oil from our hair, and then we have to add moisture back in again with conditioner. Your scalp bumps up oil production to try and replenish the lubricating oils that you removed, which makes our hair get greasier faster. If you leave your hair to its own devices, your scalp will regulate its oil production, and eventually things will even out.

It helps if we brush it regularly. To do this, the Tudors all use a simple, vital tool; the two-sided comb. One side has wider teeth, and the other has very fine teeth.

RUTH: If you're using the wide side, you're basically getting tangles out of your hair, it's about looking good. You know? It’s about getting yourself looking nice, getting groomed...it looks nice. The finer side is about getting nits out of your hair: it's a nit comb. It's about physically removing parasites that are on your head. And it works.

nits be gone!

An ivory comb showing David and Bathsheba, France 1530-50. Courtesy of the V&A Museum.

It also helps distribute the oils through your hair from scalp to tip. Comb thoroughly twice a day and your hair will be just fine. If you’re worried, though, you might brush in some fine clay powder to absorb any excess oil or dirt. If you’ve got bed hair, don’t stress over it: we’ll have our hair almost fully covered, for modesty. We’ll tie it up in either a ponytail or braid using lace or tapes. Then we’ll pop on our linen cap, then our hood, and then possibly our veil. As the period goes on, we’ll see hood shapes change, going from hexagonal to rounded, and they’ll slip backward, revealing more and more of our hair. The key thing to remember, though, is that loose, naked hair is associated with young women, a sign of innocence, which is why many wear it loose on their wedding day. For a married lady to leave it wafting around is...well, scandalous. Save it for the bedchamber!

So what about makeup? Very few women of any station were wearing it; we won’t see its popularity rise until the 1560s. Increased trade with Italy helps fan the makeup flames, but it’s also possible that its rise in popularity has another origin: Elizabeth I’s bout with smallpox in 1562. It will leave her face minorly scarred, which seems to inspire her to wear more of her famous white foundation. Everyone else, at least at court, will follow suit. For them, the desired look for most is a pale complexion: a suntan means you work out in the fields, and that won’t do! So they will coat their faces in things like lead, mercury, antimony, and vermillion. Harmful? Very. Some of their less frightening side effects include headaches, mood swings, and insomnia, but they can also cause organ damage. Cerusse, a white mineral and ore of lead, is mixed with vinegar and used as a skin whitener. It damages the skin, so the more you wear it, the more you have to put on to cover up that damage. The Tudors are aware of the problems it can cause: “those women who use it about their faces,” one guy wrote, “do quickly become withered and grey headed, because this dowth so mightily drie up the natural moisture of their flesh.” It also caused hair loss, which might be one of the reasons that wigs and the very high forehead will come in vogue later in this era. Some people have posited that Elizabeth’s increasingly volatile temper as she ages is because she is slowly being poisoned by her beauty products. So it’s a good thing that the vast majority of us won’t be messing around with any of that.

Now we slip on our shoes, which are likely to be sturdy leather with fairly thick soles, and we’re ready for action.

chapter VI: A Woman’s Work is Never Done

the working order

Before we really get going, let’s talk properly about our social ladder. We’ve already touched on how our social status affects our houses, beds, and clothes, and it will define so much of what we can expect from our day. We Tudors believe firmly in a strict social hierarchy. People, plants, and animals all have a place on the ladder that defines everyone’s place. Much of what determines which rung we land on depends on how much land we own. In the decades leading up to the 1530s, which is where we are currently, the Catholic Church and the monarch were the richest and most powerful amongst us. They had far more land than anyone else. But when Henry VIII breaks from the Pope and founds the Church of England, all that changes. He takes control over much of the Church's property through the dissolution of monasteries. So the king is far and away the country’s richest and most powerful person. Next comes the aristocracy - those who hold titles as peers of the realm. We’re talking dukes, barons, etc. These are the people who make up the Tudor court, which has its own competitive and complex hierarchy. These families have large estates, probably a townhouse in London, and multiple households with hundreds of staff. These are powerful political movers and shakers. Down the ladder from them are the gentry. Their land holdings are smaller, generally, and more concentrated in a certain region, but they’re still pretty high up the social scale. Technically, one can only count herself a gentlewoman if her family has the right to a coat of arms, but really it’s anyone who can afford not to toil for a living, instead paying others to toil for him. Being gentry is all about numbers: a certain number of pounds, servants,and types of clothing, and your ability to entertain on a certain scale. This is often who we picture when we think of Tudor England, but this is a miniscule slice of Tudor society. Most of us are living far more simply than all that.

Next come yeomen. They often rent their land from those above them on the social scale, though sometimes they own it, and they farm it all themselves. They’re sometimes richer than the gentlemen around them, but because they work their land themselves they don’t really fit the genteel brand. Yeoman are, in essence, prosperous farmers, with four or five-room houses and hired help for the farm. Below them comes what is perhaps the largest slice of the Tudor social pie: husbandmen. They farm rented lands on a much smaller scale than yeoman and don’t usually hire outside help; most of the labor is done by the family. Next come laborers, who don’t own any land and hire themselves out for a daily wage. This is a hand to mouth existence, and precarious. But you have an even less fortunate group below this one: vagrants and beggars, and those who can’t find any work.

For our urban population, you’ve got a few other categories, all similar to the ones we just covered: citizens, who are on the same level as yeomen. Merchants are the most affluent among these. They employ apprentices and servants; some of the richest even kick it with the landed elite, although they’re not always seen as their social equals. Then come craftsmen, who are aided in their work by apprentices and family members. Labourers are next, paid by the day and often struggling to make ends meet. Then, of course, we have the truly poor.

As we explored when we talked about our clothing, there are true monetary gulfs between some of these classes. There are also a lot of notions floating around about what one’s station says about them and what they are allowed to do. Tudor England is a place that wants everything in its proper place and gets upset when someone tries to dress or act above their station. We see this in the sumptuary laws we talked about earlier: the laws that dictate very clearly who is allowed to wear what. In Elizabeth I’s time, if you aren’t a member of the gentry and you decide to swan around in say, a fur-lined cloak, you’re going to be seriously rocking the apple cart. Social status is important in this world, particularly to the upper classes, and the clearest way to showcase a prosperous position is to throw down some coin. We Tudors are all about more is more: we decorate lavishly, dress to impress, and entertain with abandon. We Tudor women must know their place in the order of things - and know how to make the most of it.

YOU BETTER WORK

Now that that’s clear, let’s get going with the rest of our day. Are we eating a hearty breakfast to fortify ourselves? Yes, but only pregnant women and children eat first thing in the morning. Our first meal of the day is less a good start than a break in the middle of a very long morning.

It is a Tudor truth universally acknowledged that no matter your station or situation, a woman’s day is never idle. She has a LOT to do. John Fitzherbert, in his the Boke of Husbandry, assures us that “thou shalt have so many things to do, that thou shalt not well knowe where is beste to begyn.” He gives us Tudor ladies quite the to-do list: we will start by sweeping the house and tidying the dashboard, then milking the cows, pouring all the milk we just procured through some cloth to strain out any hair or dirt. Then we’ll wake the children and get them dressed, and only THEN will make breakfast. Yup: we’ll be making the meals as well as eating them.

Most of our work will be centered around the house itself. Here’s Ruth.

RUTH: there was quite a strong divide between men's and women's work. Women's work was everything to do with the yard. Basically, the area around the house was considered to be primarily female responsibilities. Everything far away from the house was primarily male responsibility.

I hope you like cleaning, because this task will be vigorous and constant. As with personal hygiene, we have this notion that Tudor standards of cleanliness leave a lot to be desired. Not true. The idea that cleanliness is next to godliness is alive and ever-present in this era. We might not understand exactly why dirty counters and grubby clothes make us ill, but we are very aware that they do. But to wash things, first you have to organize your water supply - we don’t have running water indoors, as a rule, and so we will have to pull it up from a well. Then we’ll get down to scouring. Our basic supplies will be horsetails - a type of plant much like rushes - river sand, and hot water. Our wooden bowls and utensils, meal prep surfaces, even rusty armor - it all needs to be given a good scrub.

Unfortunately, vermin aren’t something we can just scrub away. Fortunately you’ll have herbs in your kitchen garden that will help keep away the creepy crawlies. Fleabane will help to keep the fleas out of your bedding, while some household manuals recommend wormwood for banishing all sorts of unwanted boarders. Thomas Tusser gives us a little rhyme to remember this by: “where chamber is swept and wormwood is strowne, no flea dare abide to be known.” Just brush your floor clean, then sprinkle it about the floor. The rats definitely won’t like it. But then again, likely neither will you.

The good thing about pretty much all of our work is that we don’t have to do it all at once. We can tackle it in stages, leaving off from one thing to attend to something else around the house.

RUTH: The jobs themselves could often be broken down and sort of interwoven. A lot of these, this sort of traditional female stuff, have a lot of small processes, and you can interweave them, nipping from one job to the next. So if you think cheesemaking, buttermaking, dairying, that's a female thing, but you can do, you can break it down into like, okay, so there's the milking. Okay, that's it, that's a separate thing. And then you can put them out to one side and go do something else. And then you come back once then you can let it is sort of separated. So now you can strain off the cream. There's another little five-minute operation, go and do something else. You might come back then and do the churning of the butter. And then once that's done, put it to one side and go off into something else. And meanwhile, you put the fire on to heat the milk ready to put the rhenish in to make the cheese, and then you can leave that then to set...while you go off and do something else...you're busily interleaving lots and lots of little jobs, including changing nappies, and, you know, wiping noses, and getting the dinner on.

Some of the most important jobs on the farm are almost always done by women.

RUTH: very, sort of broadly, the areas that women took responsibility were laundry, dairy, house care, childcare, gardening.

We’ll also be making two staples of our diet: ale and bread.

ALE, BREAD, MILK

Our ale and our bread come from the same basic ingredients: water, grains, and wild yeast floating around in the air. Our ability to make both, and make them well, is central to our family’s well being. The vast majority of Tudors eat two pounds of bread and drink eight pints of ale a day. They account for about 80% of our caloric intake. Those fields full of grains are a big part of what sustains us. If you’ve got a gluten issue, this era’s going to be a tough slog.

Even in bread we see class distinctions; which bread you can afford to put on your table says something about your social place. At the bottom of the rung is horse bread, made of ground-up peas. It’s so rough that it’s mostly - you guessed it - fed to horses, but if we’re in dire straits it’ll sustain us. Maslin bread is a good worker’s staple, made of wheat and rye. It’s a lot denser than what you’re probably picturing, and it’s going to take a hardy constitution to chew through. The very finest is a white bread called manchet. It’s time-consuming to make and less filling than most other loaves, though, so you’re only likely to find it on the finest tables. Most of us Tudors don’t have ovens at home, which means we have to take our bread dough to the local baker for cooking, or use a communal oven. Just one more thing we’ll have to work into our day.

Everyone’s drinking ale in Tudor England: children, women, and men of all ages. We do this because the process involves boiling the water, making it safer to drink than what you can scoop up from the nearby stream. We’re drinking it pretty much all day, every day. One wonders if we’re low-key drunk all the time, but Tudor beer comes in all different strengths. The stuff we’re drinking is much weaker than what we’re used to in our modern era, and sweeter. It also contains a decent number of vitamins, so in moderation it’s a good source of things our bodies need. The process takes weeks: we have to capture wild yeasts, sprout our grain to transform its starches into sugar, pour some water in, and give the yeast time to turn the sugar into alcohol. Again, if our equipment isn’t sparklingly clean, our beer might end up sour and undrinkable, which would be a big-time calamity. We’re brewing enough beer for both our family AND any workers on our property to consume. It takes about six acres of wheat and barley a year to make a daily ration of bread and beer for one person. This in a time when one in four harvests fail. It’s no wonder farmers pray so much!

The problem with our English ale is that it doesn’t last: it starts to spoil after a week or two, so it needs to be made regularly and in small batches. This is one of the reasons that beer starts to take off during this time. In the Tudor era, ale and beer are not at all the same thing. Ale is flavored with something called gruit: essentially a mixture of whatever herbs we have around, from heather to yarrow to juniper. Beer is made with the addition of hops: pine-cone shaped buds that come from Humulus lupulus, a cousin of the cannabis plant. Hops serve as a preservative, which means that beer lasts longer than ale and can be taken on long journeys. Hops make their way over to England from the lowlands, and while England is one of the last places in and around Europe to really take a shine to them, we have English recipes for hopped beer as early as 1509.

Iit can pay to be a good “ale-wife” or “brewster.” There are women who make a bit of money selling their ale. Anyone who wants to sell their ale is allowed to, but they have to have it tested first by the local aleconner. If they find it too weak or in some way deficient, they can deny you the right to sell, fix on it a much lower price, or force you to tip it out into the field behind the hay loft. Let’s say the local aleconner doesn't like you because you spurned him for - oh, I don’t know - Tom Hiddleston. Tom in a codpiece is something I think we can all get behind. Might he use his aleconner power to make it hard for you to make a living? You betcha.

From June to September, when the grass is at its best and most plentiful, dairying is going to take up a huge chunk of our time. We’re not just interested in the milk, but in making cheese and butter: things that will help keep us going through the winter. This is why keeping things clean is so vital. As our friend Gervase Markham pointedly reminds us, the dairy has to be so clean that “a prince’s bedchamber must not exceed it.” We’ll assiduously clean out all dairy equipment every time we use it, which is often. We’ll get out our salt and scrub our equipment with it using a damp cloth. Next comes a good dousing with some boiling water. Then we’ll leave it all out in sunlight, whose UV light will kill any bacteria that might still be hanging around. We Tudors don’t know just why this process works, but we know that it does, and that neglecting it will turn our butter bad.

Cream is a luxury that we will only enjoy on special occasions; mostly we’ll be making cheese and butter, which we will churn by hand. We’ll have to then work salt through it to make sure it keeps, so yeah, your arms are going to be getting a workout. It’s worth it, though, because making great dairy products is something a woman can come to be well known and respected for. Itt isn’t just a matter of pride: dairying can be made into a lucrative business. Traditionally, any money made from a family’s dairy is a woman’s to do with as she pleases. For those households that outsource their cheese making, a good dairy manager is worth her weight in high-quality cheddar. In 1566, Christabel Allman will make twenty shillings a year running the dairy at Wollaton Hall in Nottinghamshire: pretty good coin for a woman of the era. Many young women aspire to become dairy maids working under the guidance of such a dairy woman.

RUTH: If you were an ambitious young woman, you would really be looking for farms that did dairying because a dairy maid was the very best female paid farming position, dairy makers could charge considerably more than any other sort of maid. It required more skill. Good cheese making is an art form. And you need to know what the heck you're doing.

THE NEVERENDING WASHING

Now that we’ve gotten our house clean, and our bread and butter and ale in order, we will turn our attention to the never-ending laundry. This is exclusively a woman’s job, and as we discussed when we attended to our personal hygiene, it’s vital to our overall health. We Tudors feel REALLY strongly about laundry: it’s our best defence against uncleanliness, and therefore the evil miasmas floating around on the air. Unclean linen invites illness, and so we will wash it constantly, and we’ll be doing it all by hand in a process known as ‘bucking’. But we won’t be using soap or hot water. If Tudor times are going to teach us anything, it’s that soap isn’t the only effective means of getting clean. Here’s Ruth Goodman.

RUTH: soap was usually used only on things like collars. If you had like a posh ruff, or you know the caps around your face, that's something you might use soap on those more delicate fabrics. If you've got a really really fine weight linen that was, you know, delicate, or lace or something like that, you wouldn't want to use the ordinary methods that would destroy it. You need this more gentle laundry method and that would mean soap. Every every other bit of linen, anything that was tough enough to take you which was pretty much everything else, your shirts, your smocks, your sheets, your your towels, everything was washed with lye, not soap and lye is a liquid that you can very, very simply produce from wood ash.

Lye is an alkali, hence the name, that we can get by pouring cold water through some wood ash. Wood ash is cheap and plentiful - just go over to your cold fire pit and grab a pail. But we don’t want to tumble pure wood ash with our best linen napkins, so instead we’ll create a kind of filter out of straw, put the wood ash on top, and pour some water through. We’ll end up with a very strong solution that’s going to do a bang-up job of cleaning our clothes.

RUTH: So the simplest thing to do was to take your laundry and put it into some basket, bucket, it didn't matter what - baskets were quite common. Set it up in a couple of bricks, put all the most dirty greasy things in it. And then you just take a jug of this liquid that you strain through water with the wood ash and just pour it on top and let it just drip through slowly, and it will dissolve all the grease as they go…

The next step is going to take some brute strength and is a great way to get out any pent-up frustration.

RUTH: you take your washing to a water source where you might have one in your yard, or you might have to go to the local stream. And then when you get there, if you take a little stool with you and set it in the water so that even if you have to sort of stand on the stones and you've got a stall to put the clothes on, you don't come in the water put them on the stool, and hit them with a big stick. Hitting with a big stick drives the water under pressure through the fibers and that of course forces dirt away…

Bang, bang, bang: bash your linen. It’s a spin cycle, but fuelled by you! Then we’ll leave our clothes out in the sun. Linen gets its signature whiteness with regular washing and sun bleaching, and crisp whites are a sign of wealth and cleanliness. If you’re a washerwoman, it’s in your best interest to advertise how very white you get your whites.

Most nobles pay a woman to do their laundry for them, and it’s often a highly respected position. In this era, working positions at the Tudor court are quite limited for women; at Henry VIII’s court, the laundress is the only permanent female staff. And she’s important: not just anyone is allowed to touch his highness’s underthings! She’s recorded as making 10 pounds a year for her trouble. She’s even given some gardens at Westminster. She’s earned it, I reckon: one of the methods for cleaning an extravagantly embroidered shirt without ruining its stitchwork involves soaking its cuffs and ruffs in urine. Fun fun! The royal laundress has a role that’s both important and sensitive, especially when it comes to doing laundry for queens. Case in point: before Katherine of Aragon could marry Henry VIII, she was put through a sort of inquisition to find out whether her marriage to Henry’s elder brother, Arthur, was ever consummated. During the ordeal her laundress was actually brought in to testify, presumably because she’d have handled bloody underthings or sheets. Elizabeth the First will have just two laundrywomen over the course of her entire reign, who will travel with her everywhere. Very few people are allowed to deal with the queen’s menstrual rags.

We ladies will have other household duties, too. We’ll keep busy feeding livestock, gathering eggs, and tending to our gardens. It isn’t just for looking pretty, either: we’ll be growing plants and herbs here that are central to our cleaning, our cooking, and our family’s health. We will be distilling, preserving, and drying herbs to use for medicine. We ladies are our households’ primary care physician.

LADY PHYSIK

Our life expectancy in Tudor times might shock you. The average in the early sixteenth century is barely thirty years old. That number is heavily skewed by our infant mortality rate: some 25% of children die before their first birthday, and 50% before their tenth. So death is an ever-present specter, and our family’s healthcare is quite vital, but some of our ideas about how are bodies work are not what the modern lady might desire. We believe in a notion that stretches back to ancient times: that everything on earth, including our bodies, is governed by four elements: fire, earth, air, and water. Each of these has a character. The same can be said about the four humors that make up our bodies: blood, red choler, black choler, and phlegm. The exact balance of each varies from person to person, but some differences boil down to our sex. Men have more of the blood humor, so they tend to run hot and dry. This, of course, makes them vigorous and virile. We ladies, by contrast, have more phlegm, so we are naturally cold and damp, and thus are weaker, both mentally and physically. Look, I don’t make the rules: that’s just science.

Healthfulness is all about keeping these fluids in balance. If any of these humors get out of whack, we’re bound to get sick, and we’re unlikely to have a trained doctor nearby to tend to us. Most doctor training at this time is very...shall we say...academic. Most doctors aren’t doing any practical learning or dissection. Most believe that just by looking at a patient’s urine they can read the balance of our humors, almost like they’re reading tea leaves, and advise the apothecary about what they should prescribe. They’re expensive, anyway, so most of us are just going straight to our apothecary. Or the local barber-surgeon, who will do everything from cutting your hair to pulling out a tooth to performing a little surgery. No thank you! Many towns don’t have any of these options readily available, and there are few hospitals. No wonder most of us just tend to our own with herbal remedies.