Blood Magic: A History of Menstruation

It’s an issue we’ll tackle in every era, and one The Exploress loves bringing into the light. That’s right: we’re talking about menstruation. People of the past often feel like a different species, but when you remember that Cleopatra, too, had to figure out what to do when caught out without period supplies, or that Elizabeth I might have had to deal with bad cramps during meetings, it gives us insight into their lives and provides a visceral link to the women of yore. So let’s dive into the history of the period: the beliefs it’s inspired, the sometimes wild notions that’ve built up around it, and how people have dealt with them through the millenia.

But first, a disclaimer. This podcast focuses on the lives and times of women in history. What defines womanhood? Now that’s a complicated question. This episode is about women who menstruate, or have done so at some point, but I don’t mean to suggest that only women menstruate or that all women do. No one should be defined by their anatomy, and identity isn’t dictated by the body we have and what it does. When I talk about women who menstruate, I’m also talking about people who menstruate. With over 800 million people doing it daily, and roughly half of the world menstruating at some point in their lifetimes, this topic is one we could all stand to explore.

MY RESOURCES

Menstrual Taboos: Moving Beyond the Curse. The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Menstruation Studies.

Blood Magic: The Anthropology of Menstruation by Dr. Thomas Buckley.

Women’s Life in Greece & Rome: a sourcebook in translation. Mary R. Lefkowitz and Maureen B. Fant.

The Curse: A Cultural History of Menstruation by Janice Delaney, Mary Jane Lupton & Emily Toth.

The Vagina Museum. What a wonderful resource! They have great merch, too.

The Museum of Menstruation (MUM). It’s a confusing site to navigate, but there are some gems to be found.

“A Glimpse at Women’s Periods in the Roaring Twenties.” JSTOR.

“Great Moments in Menstrual History.” By Maggie Mertens. The Cut.

“The Secret History of Menstruation.” JSTOR.

“The Tampon: a History.” The Atlantic.

“The Mystical, Magical Properties of Period Blood.” Hanna Brooks Olsen, Medium.com.

“Some Cultures Treat Menstruation with Respect.” NPR. Susan Brink, Aug. 2015.

“More Than Just a Punctuation Mark: How Boys and Young Men Learn About Menstruation.” Journal of Family Issues 32(2).

“Menstruation Study Finds Over 5,000 slang terms for ‘period’.” Roison O’Connor, The Independent.

“Feminine Hygiene Products.” The Smithsonian Museum.

The World Health Organisation on virginity testing.

“Tampon Safety.” National Center for Health Research.

Resources for those who want to find out more about period poverty:

https://www.globalcitizen.org/en/content/period-poverty-everything-you-need-to-know/

https://www.actionaid.org.uk/our-work/womens-rights/period-poverty

episode transcript

please keep in mind that 1) I chop and change a bit as I record, so this transcript won’t be 100% accurate, and 2) I like using sarcasm on my show, and that doesn’t always translate well onto the page.

THAT EPIC FORCE

Let’s start with a quick period primer, just so we’re all on the same page. What is menstruation, exactly? Menstruation — aka having your period — is when a person’s uterus sheds the lining it’s built up during the course of the menstrual cycle - the lining that’s designed to cushion a fertilized egg. It exits via the vagina over the course of what’s usually a couple of days. It happens, on average, once a month. Most who get a period will have, on average, about 500 of them in a lifetime. That adds up to about 2,500 days, and if my math is right, 6.8 years of menstruation time: woo, that’s a frequent companion!

Throughout time, and pretty much the world over, we see cultural taboos about menstruation: customs and beliefs that make it ritually unclean, spiritually potent, and even dangerous. Lots of cultures have believed it has the power to pollute their surroundings and, specifically, to endanger men. Ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle believed that if a woman with her period looked into a mirror it would cloud over, such was her force during that time. Menstruation not only affected her eyes, which after all were full of blood vessels, but also had the power to disturb and distort the air around her, forming a sort of angry female cloud.

Ancient Romans also feared the mystical power of menstruation. Pliny the Elder, bless him, wrote that if a woman got her period during a solar or lunar eclipse she could kill a man just by having sex with him. This is an idea we’ll see crop up throughout the ages: that period blood has the power to damage a male member. But it could also be a force for good...kind of. If a menstruating woman hiked up her skirts and walked through a field, she had the power to kill crickets, locusts, you name it. Apparently this phenomenon was first observed in Cappadocia during a particularly bad beetle infestation. A bunch of menstruating women walked through the fields with their skirts hiked up to their buttcheeks and those beetles fell dead right off the corn. This isn’t so much about period blood being a boon, per se, but about it being SO potent that it has the power to kill plagues. Sort of a backhanded compliment.

But wait: there’s more! Pliny has tons to say about menstruation:

“...there is no limit to the marvellous powers attributed to females. For, in the first place, hailstorms, they say, whirlwinds, and lightning even, will be scared away by a woman uncovering her body while her monthly courses are upon her. The same, too, with all other kinds of tempestuous weather; and out at sea, a storm may be lulled by a woman uncovering her body merely, even though not menstruating at the time.

”

Who knew a strip tease had the power to soothe the ocean? Next time you’re caught in a storm at sea, you know what to do. Pliny also tells us that it’s a well-known fact that the touch of a menstruating woman does a lot of damage: it can make bees forsake their hive, turn boiling linen black, blunt razors, and contaminate anything purple. Alrighty.

Throughout history, we’ll see the idea crop up that menstrual blood itself is potent, even magical, but its properties are almost always sinister. In ancient Egypt, menstrual blood was considered a source of both good and evil. While an inscription at the Hathor temple says that one god listed among his chief dislikes a menstruating woman - rude - menstrual blood was also considered medicine. It was added to all sorts of drugs, ointments, and salves. One papyrus scroll suggests that if a woman had droopy breasts, for example, smearing some menstrual blood on them would perk things right up. Even our Roman friend Pliny has to admit that, “baneful as it is”, period blood has potentially useful applications. Especially when it comes to breaking spells. “Another thing universally acknowledged, and one which I am ready to believe with the greatest pleasure, is the fact that if the door-posts are only touched with the menstruous fluid, all spells of the magicians will be neutralized.”

It makes sense that period blood is often linked to magic. In times when we understood little about how our bodies worked, the whole thing seems magical indeed. It’s unique from other forms of blood: it doesn’t clot like a wound, and it can’t be stanched; it arrives and departs on a regular schedule and is typically associated with a particular sex. The period has also long been linked to the moon. Etymologically speaking, the word menstruation comes from the Latin word menstruare, from menstruus, meaning “monthly”, which stems from mensis, or moon. It’s been associated with the moon in several religions - makes sense, given it works on a monthly cycle - a moon deities are almost always depicted as female. In Mayan mythology, menstruation’s origin story comes from the Moon goddess, whose monthly flow was given to her as a punishment for sleeping with the Sun god when she’d been told not to. How dare you! Her blood was stored in thirteen jars, where it transformed into snakes, insects, poison, and myriad diseases used as an ingredient in potions. Many cultures around the world have seen menstruation as making a person more powerful. In North America, the Cherokee people traditionally believed that menstrual blood gave women special powers that let them destroy their enemies. Her blood makes her potent - it gives her spiritual powers. But that also means she might become a danger to the world at large.

It’s no surprise, then, that in many cultures those who menstruate have been kept isolated from the community during their monthly, sent off to huts to wait it out. This has been painted as something akin to period jail, but anthropological studies suggest this isolation isn’t always punishing. These huts have also served a space for rest and reflection, crafts and bonding, and a break from domestic demands. In some communities in the Hindu Kush, there’s a bashali (or large menstrual house), which serves as a kind of all-female clubhouse. It is a secret and venerated space; it’s even considered holy.

Some cultures haven’t made it either good or bad, but acknowledged its potent power. Amongst the West African Beng, women aren’t supposed to go into crops, but not because it might hurt the harvest: because mixing biological fertility with vegetable growth might actually mess with their childbearing. In the non-Western world, there are plenty of rituals surrounding a woman’s first bleed that acknowledge and respect it. Traditionally, amongst the Asante in Africa, girls getting their first period are celebrated, seated beneath a queenly umbrella and given gifts. The euphemism often used to tell an Asante queen mother that a girl in her community has gotten her first period is a phrase that translates to, “she has been made perfect.” The Ojibwe people of North America have a ritual for a girl’s first menstrual cycle: she fasts from eating strawberries for a full year, marking their transition from childhood to adulthood. It’s a time to learn wisdom from older women in the community, and to connect to one’s ancestors. A link to the future and the past.

And yet you’ll find that beliefs about menstrual blood’s destructive power are pretty pervasive. In England during Tudor times, there were those who thought that a woman’s menstrual blood was dangerous, even poisonous, and could seriously harm a male member. A child born from having sex during menstruation would end up - gasp! - a redhead, and potentially deformed.

Menstrual blood has been coveted for use in charms and potions of all kinds, most particularly love potions. In France during Louis XIV’s time, it was added to perfumes to attract a potential lover’s attention. One of the Sun King’s mistresses sprinkled such concoctions on his meals to keep him keen. The belief that menstrual blood might inspire fond feelings continues in some quarters. Try Googling “magical uses for period blood” and you’ll see what I mean. In 2009, an Indonesian maid appeared in a Hong Kong court accused of adding some to her boss’s food, hoping to make their relationship better. It seems it didn’t work the way she hoped.

BLOOD IS BAD, BUT PERIODS ARE NECESSARY

Part of the confusion in past eras about the period evolved from how little we understood the workings of our bodies. In 1540 English physician Thomas Raynold argued that surely period blood couldn’t be evil, as menstruation was clearly an ingredient in fertility. But very few women were writing down anything about periods until very recently. Hildegard von Bingen, a medieval nun and visionary, wrote about how she thought menstrual blood could cure things like leprosy. But she was the exception, not the rule. The less we talked about it, the more it became a mysterious secret, which only added to its mystical power and the anxieties surrounding it.

The act of menstruating has also been considered important for health. Greek physician Hippocrates tells us that because women are softer and more sponge-like than men, they run the risk of filling up with fluids. If not expelled, she could drown in her feminine essence, or be driven crazy by it. This is especially true of virgins. He says they often have bad dreams and visions during their first menstrual episode: yes, the “women on the rag be acting crazy” stigma goes alllll the way back. But don’t worry - he has suggestions for how to stimulate a lost menstrual cycle. It involves cow dung, beef bile, and myrrh. Ah, Hippocrates. He also has opinions about what the length of a woman’s period portends: If it’s longer than four days, then her eggs are probably delicate. Not good. But if it’s less than three days, women tend to take on a masculine appearance and are unlikely to conceive at all. That’s a pretty small window of feminine healthfulness! In an age when your ability to rear healthy babies was paramount, the length and characteristics of your flow were things you weren’t likely to advertise.

And yet it’s an issue that sometimes bleeds out into the public sphere, especially if you’re a public figure. Katherine of Aragon, English king Henry VIII's first wife, famously suffered from irregular periods, and a lot of people knew about it. France’s Marie Antoinette kept her mother back in Vienna well informed about how her downstairs area was flowing. Two centuries earlier, Catherine de Medici employed a wide range of people to document her daughter’s cycle. Ugh, mom!

One of the reasons periods have historically been watched so closely is because of its role in signalling the shift from childhood to adulthood, in some eyes, marking a person as ripe for marriage. England’s Margaret Beaufort got married and gave birth to future king Henry VII at the age of just thirteen. Oh my.

Let’s follow this swiftly darkening rabbit hole a little further to another troubling blood-related tracking device: The traditional practice of checking the sheets after a married couple’s first night together to see if the woman has bled, ensuring she went to bed a virgin. Yikes. The blood in this instance comes from the hymen: a thin tissue surrounding the vaginal opening. The idea is that when someone is penetrated for the first time, the hymen breaks, which causes bleeding. But here’s the thing: the hymen stretches. And it doesn’t ordinarily cover the entire opening, so really, there’s no need to break the thing in order to have penetrative sex. So hanging our hats on blood-stained sheets for signs of our virginity, which is really just a social construct anyway? These were seriously troubled waters for women of the past, and even now. Doctor-conducted virginity tests have been around forever, and are still happening. These tests, which the UN has called a human rights violation, have been recently documented in at least 20 countries. The results can determine whether someone can marry or get a job, and even test if she’s a rape victim. Not only is this a violating and traumatizing test, but the results aren’t in any way reliable. And yet those results have serious consequences. In Afghanistan, where sex before marriage is considered a moral crime, hundreds of girls have been subjected to virginity tests and been jailed for failing them.

THE CURSE

It’s interesting that, in some instances, a person’s period has been considered a matter for public discussion and interpretation, when we’ve spent millenia finding ways to make menstruation shameful. The Bible certainly didn’t do those who menstruate any favors. In most of our major religions, we see the notion of menstruation being ritually unclean. In the Hebrew Bible, the book of Genesis, explains that Eve disobeyed God by eating a forbidden apple, so he cursed her with the pain of childbirth. Leviticus talks a bit about the pains of menstruation and all the activities that menstruating women must not do. Over time, these two stories got tangled up, so that menstruation became a curse as well. The Old Testament also says that a woman on her period is considered “unclean” for seven days, and that any man who lies with her in that time will be considered unclean too. One biblical passage says they should both be cut off from the community. Period shaming goes back a long way. Maybe that’s why women have traditionally had a tough time in some of our major religions becoming authority figures.

Misinformation has long been part of the problem. Period blood isn’t a body’s way of flushing out toxins; nothing about it is damaging. It’s not even blood, really, but a mixture of blood, mucus, bacteria and uterine tissue. Not a magical, damaging substance that can kill bugs and damage all it touches. And yet feelings of shame and perceptions of uncleanliness are still holding pretty strong. This, in turn, often makes us want to hide it. In 2010, a study in Sweden showed that only 38% of women suffering from excessive menstrual bleeding told their doctors about it. In 2018, an article in medical journal The Lancet in the UK suggested that nearly 80% of adolescents who menstruated had experienced worrying menstrual symptoms, but didn’t go to see their doctor about it; 27% of them said it was because they were too embarrassed to discuss it.

It doesn’t help that, even in our language, we’re reluctant to talk about the period explicitly. We tend to use euphemisms: a study conducted in 2016 asked people in 190 countries what terms they used to talk about menstruation, which revealed some 5,000 slang terms. Some of the most common around the world are Aunt Flo, that time of the month, that thing, being on the rag, the red tide, lady time, and strawberry week. The Danes get lyrical with “painters in the stairway” and experimental with Der Er Kommunister i Lysthuset ("There are communists in the gazebo").

Even in advertisements for period products, we’ve struggled to call a spade a spade. Historically, even pad and tampon companies didn’t want to talk about it in frank terms in their advertising. Instead they offered big, blown-up slogans like “Free from Embarrassment!” And “Hygienic freedom!” In one Kotex pamphlet, called As One Girl to Another, from 1940 suggests, their pads would: “never make tell-tale outlines […] [and] never give your secret away.” In America, advertising menstrual products on TV was banned until 1972, and it wasn't until 1985 that someone actually said the word ‘period’ in a national pad commercial. That someone was a young Courtney Cox.

Because it’s been framed as some kind of shameful secret, and linked with uncleanliness, a lot of people who menstruate try to hide the evidence and are reluctant to talk about it. Many don’t really understand it. Figures from the Eve Appeal from 2019 suggest that 1 in 4 young menstruators didn’t know what a period was until they had one. That ignorance also extends to those who don’t menstruate. Here’s a telling anecdote: before Sally Ride became the first American woman to go to space in 1983, NASA engineers asked her a LOT of anxious questions. Would 100 tampons be enough for a weeklong journey? Spoken like people who had never had a frank conversation with their menstruating loved ones. Studies show that most boys - in America, at least - first learn about periods from family members, usually sisters. But a lot of the boys surveyed said no family member ever spoke to them about such things. And not all sex education is created equal.

And now, a funny period supply ad for you! We’ve come a long way:

PAD ME, PLEASE

Let’s move on from menstruation itself and look at the things we’ve used to actually deal with it in the moment. To begin, we should acknowledge that people of the past probably had fewer periods than we do. Blame it on poor nutrition, shorter lifespans, and the tendency to have children early and often. But when they did, they didn’t have the option of running to the store for a box of tampons. What, historically, have we used to stanch the flow?

We don’t have a lot of evidence from the long-ago past in terms of what period supplies were used, for many reasons, but it makes sense that those who menstruated were reaching for whatever they had. And mostly, that meant some kind of homemade pad. Ancient Egyptians seem to have had some kind of loincloth situation. We know this because, in a papyrus scroll that describes a list of unpleasant professions, we learn how much it sucks to be a laundryman: specifically, because he had to handle women’s stained underthings. In Medieval European times, there was a common type of super absorbent bog moss. Some think it got its most popular nickname, “blood moss,” because of its use on the battlefield, but others think it earned its name because of how often it was used to soak up other kinds of blood. But the easiest and most likely solution for pretty much all of history was some form of rag, usually linen. There’s a reason that one of our most popular euphemisms for having one’s period is being “on the rag.” These were fairly easy to come by and then to wash and reuse.

from MUM (the Museum of Menstruation).

But for most of history, women weren’t wearing what we consider underwear, so how were they keeping these rags in place? Again, it’s murky, as most women were making these supplies themselves at home. But advertisements that started cropping up in the Victorian era offer clues to how some might have worked. Most of the commercial sanitary products on offer involved belts that you could attach a reusable cloth to. So basically, we’re still working with the Egyptian loincloth situation. These were still in prevalent use in my grandmother’s time. If a belt wasn’t your style, these ads suggest you try a pair of suspenders, which kept your menstrual “bandage” where it was meant to be. As you’d imagine, these things could be bulky and uncomfortable.

The commercial pad doesn’t seem to have really hit its stride until World War I, which spurred a lot of innovation in the realm of bandage technology. The Sfag-Na-Kins took a page from medieval period history by using sphagnum moss. Grown in the Pacific Northwest, this Portland company processed the moss and wrapped it in a gauze covering. Its packaging even featured a Red Cross “Sphagnum Moss Girl,” nodding to its connection to wartime field dressing. Kotex napkins, introduced in 1921, were also developed from the same technology used on the battlefield. They used the same cellucotton, a wood pulp product, enclosed in gauze. Strong marketing meant strong sales, and the sanitary napkin industry really took flight.

And now, a funny period supply ad for you! We’ve come a long way:

MY KINGDOM FOR A TAMPON

The history of the tampon, like all of period history, is shrouded in mystery. The tampon as we know it wasn’t invented until the 1930s, but there were tampon-like things around LONG before that. There’s evidence to suggest that women in ancient Rome made tampons out of wool, for example, and that Egyptian ladies might have used ones made of papyrus. People have used whatever they had in their parts of the world: Indonesian women have used vegetable fibers, while some in Africa have used rolls of grass. A book about tampons from 1981 says that adventurous Hawaiian women have traditionally used the furry part of a native fern to soak up their business. In ancient Japan, another says, they used paper secured in place with bandages, which absorbed liquids so fast they had to be changed 10 to 12 times a day.

The word “tampon” comes from the medieval French word tampion, or “plug,” a variant of the Old French tapon, or "piece of cloth to stop a hole". In 1860, author R. G. Mayne defined a tampon as: “a less inelegant term for the plug, whether made up of portions of rag, sponge, or a silk handkerchief, where plugging the vagina is had recourse to in cases of hemorrhage.” Commercial hole stoppers didn’t start showing up on the scene until around the same time commercial pads started appearing. Most tampons were used not for managing one’s flow, it seems, but for getting medicine into the cervical region and for contraception. In 1880, U.S. gynecologist Paul Munde described eight different uses for a vaginal tampon - retaining the shape of the cervix, say, or helping with a prolapsed uterus. Only one of those eight was for the absorption of fluids; menstruation wasn’t mentioned in his work at all. In the 1870s, ads started appearing for Britain’s “Dr. Aveling’s Vaginal Tampon-Tube,” a complex contraption that involved an applicator made of glass and a glycerine-soaked tampon made of cotton and wood. Go gently there, time travelers! Into the early twentieth century, nurses were using tampons - a plug of antiseptic wool wrapped in gauze, with a string to help with removal - for clinical purposes. They were meant to break open the little capsules of antiseptic liquid that came with them before ramming them home. They were used to treat wounds and infections, and usually couldn’t be found outside a hospital.

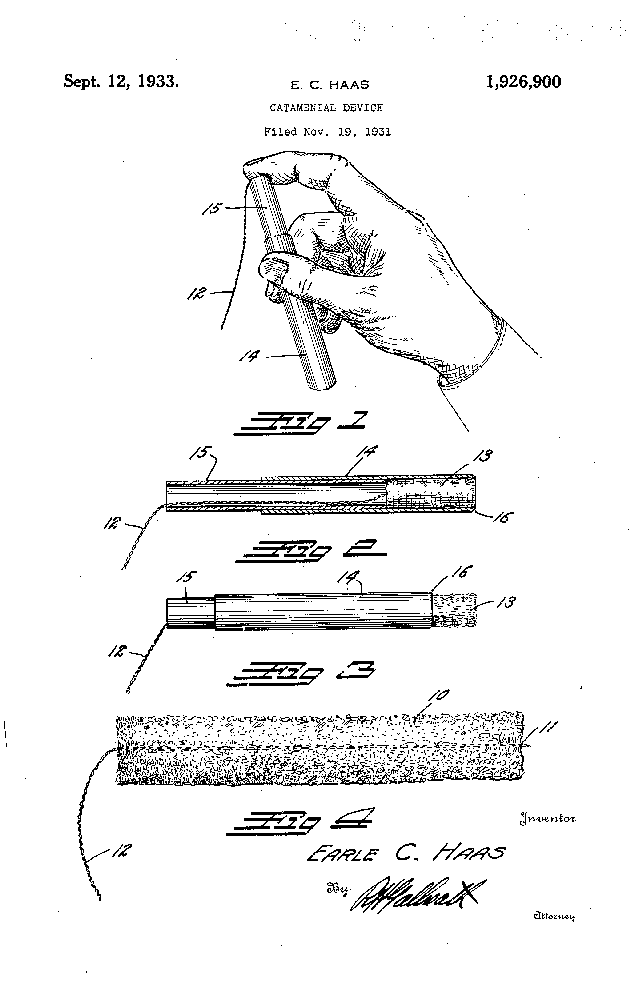

And then came World War I. The same innovations that fuelled the commercial pad industry also fuelled a rethink about tampons. There’s a wonderful myth about the guy who ALMOST invented the tampon in the 1920s. A Kimberly-Clark employee named John Williamson poked some holes in a condom, stuffed it with the materials used to make commercial pads, and went to his dad, a Kimberly-Clark medical consultant, to pitch it as an insert for menstruation. Dad, horrified, told his son: “Never would I put any such strange article inside a woman!” And so it’s Colorado physician Earl Haas who gets the credit for the first menstrual tampon, patented in 1931. One version says that a female friend is the one who inspired him, after she told him she preferred to insert a sponge into her cervical palace rather than use a pad. I like to imagine them having this chat in the middle of a fancy dinner party. The conversation made him think of his wife, who was a ballerina, who struggled to dance wearing a bulky pad.

Mr. Haas's tampon patent.

sourced from Wikicommons.

Part of the reason it took these products a while to take off is that there was still a whole lot of shaming around the whole issue, which meant women didn’t want to talk about it. A lot of women in the 19th and early 20th century didn’t bother going to their mostly male doctors about anything period related, even menstrual pain, because they knew what he’d say: that they were probably her fault. In 1850s America, one doctor attributed period complaints to “prurient incitement of passion-stirring pictures, statues, music, novels, and theatres.” Another blamed a premature menstrual flow on a woman’s having gone into the city and eaten too many exciting foods. Maybe you shouldn’t have had so much pasta, lady! After all, as a 1920s Kotex booklet called Preparing for Womanhood says, menstruation caused: “...less muscular strength, less steadiness – and even less mental efficiency.” Thousands of years beyond Pliny and Hippocrates, all that stuff about how periods make people weak and potentially unsound of mind was still being passed around.

And menstruation was still being used as a means of judging women. There were those who believed that a worryingly heavy flow was a sign that one was having too much sex, which was bad even if it was only with her husband. And when it came to menstrual tampons, WELL: they meant that a woman would have to touch herself, DOWN THERE, and she might accidentally get PLEASURE from it. She might also accidentally break her hymen, and then how would her future spouse know she’d been chaste? Ohhhhh my.

Mr. Haas knew he needed to combat these beliefs by coming up with a way she could insert the tampon without risking any such calamity. He took his inspiration from the telescope, creating something that a woman could insert without ever touching her sensitive region. It’s interesting to me that we think a man could be the one to “invent” a tampon - really, all he ever did was find a way to profit from it.

Later, a lady named Gertrude Tendrich bought his patent for $32,000. She expanded production from sewing tampons at home to creating the first commercial tampon brand, Tampax. The name was a mashup of the word ‘tampon’ and ‘vaginal packs’, the phrase most often used to describe feminine hygiene helpers. Pads remained the most popular option, but by the mid-1940s tampon use had expanded fourfold from where it started. Around that time, a German gynecologist named Judith Esser-Mittag developed a digital (aka applied with just a finger) tampon that would come to be called the O.B. tampon.

As the decades rolled on, the tampon offerings grew. In the 1970s, some feminists started to question why they should hide or stem the flow of their periods. But this is also the era that saw a shift in the tampons on offer. In 1975, Procter & Gamble tested its first feminine-hygiene product—a tampon called Rely. Shaped like a tea bag and made to expand both widthwise and lengthwise, it contained a host of chemicals. One was carboxymethylcellulose, or CMC. Chips of it made the tampon hyper-absorbent; some, it’s been said, could wear it for an entire period without taking it out. Japan banned its import because of its ingredients, but because of a loophole in U.S. legislation they weren’t subject to any rigorous tests, and made it to market. At that time, tampon manufacturers didn’t need to list any of their tampon’s ingredients. In many countries, they still don’t.

In 1978, The Berkeley Women’s Health Collective complained about it. In a pamphlet, they blamed manufacturers for ignoring the risks. And yet Rely was popular: by 1980, some researchers say, nearly a quarter of tampon users were buying it. Then, between October of 1979 and May of 1980, 55 cases of toxic-shock syndrome were reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Seven of those women died. A link between tampon use and TSS was suspected, then proven. It turns out that leaving a chemically-starched piece of compacted cotton in your cervical palace for several days makes toxic shock more likely. By 1980, a total of 812 menstruation-related cases were reported, 38 of them fatal. All tampon companies fielded lawsuits, and Rely was pulled from shelves.

Though some are nervous about tampons, they remain a popular option. One study from 2015 found that the average American woman is estimated to use more than 12,000 tampons in her lifetime. And more patents are being filed all the time: in the past five years there’s been one for a tampon with a saturation indicator and even a vibrating tampon. I’m going to give that one some serious side eye, but you know what? You do you.

The thing is that pads and tampons are one-use only, so not that environmentally friendly, and pretty expensive. Some countries have taxed tampons as luxury items. Like my adopted country of Australia, which until fairly recently added 10% goods and services tax on feminine hygiene products because they weren’t deemed essential. One Mr. Wooldridge had this to say about the move: “As a bloke, I’d like shaving cream exempt, but I’m not expecting it to be.” Spoken like someone who’s never bled through his jeans. Even the more sustainable alternatives, like reusable underwear and cups, require you to shell out some money up front. There are many situations where such supplies are hard to find, and too expensive. In America, sanity supplies aren’t covered by food stamps. Hence the rise in period poverty, which is defined as a situation where someone’s unable to access period products. The situation can have serious consequences: missed school or work, and the possibility of physical harm or mental distress. Plus, we live in a world where many are embarrassed to go without.

But not everyone. There have always been women who question why we should go to all this trouble to stop and hide our flow. Take Kiran Gandhi: In 2015, she woke up to run the London Marathon and discovered she was on the first day of her period. She had a choice: run in a chafing pad or uncomfortable tampon, or just...flow freely. She decided to prioritize her own comfort and not wear anything. A brave and, as she wrote later, freeing act.

Perhaps that has something to do with the rise in drugs that let you skip your period. One study in particular found that in our era, some 59% of the American women surveyed said they’d rather not menstruate every month. Of these, a third said they were interested in not menstruating at all. There are plenty of reasons for this preference: it’s messy, period supplies are expensive, menstrual symptoms are disruptive and, for some, the experience is upsetting for a host of reasons. And opposed to what many doctors of the past - both ancient and recent - have told us, most people don’t actually NEED to bleed to be healthy. But no one should feel ashamed to do so.

There’s a lot more to say on this topic, and it’s one The Exploress will keep coming back to. Given the misunderstandings and anxieties that our silence on menstruation has spawned, I think we should all talk about it more than we do. That’s why I’m here, proudly sharing historical period facts with you. I hope you’ll go forth into the world and do the same.

***

All of the episode’s royalty-free music comes from Storyblocks.com and Epidemic Sound.